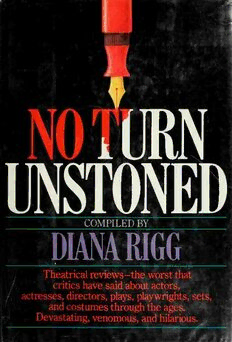

No Turn Unstoned: The Worst Ever Theatrical Reviews PDF

Preview No Turn Unstoned: The Worst Ever Theatrical Reviews

COMPILED BY Theatrical reviews-the worst that critics have said about actors, actresses, directors, plays, playwrights, sets, and costumes through the ages. Devastating, venomous, and hilarious. N.T.U. $16.95 NO TURN UNSTONED DIANA RIGG In NoTurn Unstoned Diana Rigg has gathered together a treasure-trove of awful theatrical reviews-a fascinating and frequently hilarious survey of the worstthatcriticshavefoundtosayabout actors, performances, sets, writers and directors through the ages. Nogiantofthe stage hasescapedtheir vitriolic pen. Laurence Olivier, Dame Peggy Ashcroft, Sarah Bernhardt, Glenda Jackson, Katharine Hepburn, Maureen Stapleton-they have all been sufferers. They said that Diana Pugg 'is built like a brick mausoleum with insuf- ficient flying buttresses'; Sir John Giel- gud has 'the most meaningless legs imaginable'; and Tallulah Bankhead 'barged down the Nile last night as Cleopatra and sank.' All actors re- member their own worst reviews and, here, a number have contributed theirs withwrycomment. Alec McCowen, for instance, recalls this with a shudder **?N7D about his performance in Luther: 'an inspired piece of miscasting...a frail schizoid pixie in a robust cycloid role... it helped ifyou shut your eyes.' And plays too. Classics like The Birthday Party were, greeted with out- mmmt (continuedon backflap) / NoT, oned TheWt orstEver Theat nca^ey iews Coi npiled b NANA RlGG BRAR 1983 Designed by Craig Dodd LibraryofCongressCataloginginPublicationData Mamentryundertitle: NoturnunstonecT Includes index. — I. Theater Reviews. I. Rigg, Diana. PNI707.N58 1983 792.9'5 82-46071 ISBN0-385-18862-5 © 1982DeclutchProductions,Ltd OriginallypublishedinGreat BritainbyHamishHamilton All RightsReserved Printed intheUnitedStatesofAmerica Content* Introdi Action 7 1 sActosr< rs—- 2 ACri fjic's Devi C)e 49 ^ "^•nBH Pi, fain 65 Musicals, „ ^fars 93 5 %j*« Across the m 09 C/ass/c Kol,e « 137 7 Oirecr<° r^ Prodi fu Sett a«d Th <*ioi,s, leatres 8 J59 Miscelh fany 1 75 "BiWb'liography 189 "idex ion 850182 Acknowledgements I would particularly like tothankall thecritics whonotonlygenerously allowed me touse theirtexts, butalsogavegreatencouragement; Molly Sole of The Old Vic; John Goodwin of The National Theatre Press Office; Levi Fox of The Shakespeare Institute; Angus Mackay for his tireless research and profound knowledge of matters theatrical; John Lonsdale and Colin Wilson ofThe Times Library for helpwith research, and John Lonsdale for the index; John Adrian, Frank Muir and Bevis Hillier; Martin Tickner and Sheridan Morley; Frances Koston; Dorothy Swerdlove of The New York Metropolitan Museum Theatre Library. Jenny Pearsoncomesat theendofthis paragraphonlybecause Iwish to say a greatdeal more about her and hercontribution. Jenny is a writer, yet out of friendship and enthusiasm for the project undertook to help not only research, but the wearisome business of transcribing tapes, sourcing, and generally pulling the book into shape. It was her gentle guidance that kept me going when I flagged, her skill that transformed my plodding prose into the readable. In short, without Jenny there would have been nobook. I, and my publishers, would also like to thank the following for permission to use copyright material: Punch Publications Ltd for many illustrationsand someextracts; George Harrap Ltd for the illustrations by Nerman from Caught in the Act; Raymond Mander and Joe Mitchenson Theatre Collection for all the other illustrations. The Daily Telegraph, inparticularforthereviewsof W. A. Darlington; The SocietyofAuthorsastheliterary representative oftheEstateofSt. John Ervineand the EstateofGeorgeBernard Shaw; the Trustees of the British Museum, the Governors and Guardians of the National Gallery ofIreland and Royal Academy ofDramatic Art for the letter from George Bernard Shaw to Wendy Hiller, © 1982; Walter Kerr and Brandt and Brandt Inc, New York; Clive James(from Visions Before Midnight published by Cape and Picador and Glued to theBoxpublishedbyCape); The Literary ExecutorsofJamesAgateand George Harrap Ltd; Mrs Eva Reichmann and the Estate of Max Beerbohm; The Observer and Robert Cushman; Times Newspapers Ltdfor reviews by Irving Wardle and Ned Chaillet; Random House Inc for the extracts by John Simon from Singularities; Mrs George Jean Nathan for the extracts by George Jean Nathan from The Theatre Book of the Year 1943-44 through 1950-51; Harper and Row Publishers Inc. for the extracts by Stanley Kauffman from Persons of theDrama; Express NewspapersLtd fortheextractsby Hannen Swaffer; the Estate of Kenneth Tynan for extracts from A View ofthe English Stage published by Davis-Poynter, Curtains, He That Plays The King and Tynan Right and Left published by Longmans; John McCarten in The New Yorker © 1945, 1973, reprinted bypermission; and Andrew © D. Weinberger for the extracts from The Portable Dorothy Parker, 1973 The National Association for Advancement of Colored People, first published in The New Yorker. Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders, but, should there be any omissions in this respect we apologise and shall be pleased to make acknowledgement in any future editions. 'A critic is a man who leaves no turn unstoned,' as my friend the Reverend Joseph McCulloch once remarked to me, and from this maxim came my idea for the book. It followed, surely, that everyone in my profession must, at some time, have beengiven abad notice. So I wrote to all the well-known actors and actresses of today and asked them to donate their worst/funniest review. A delicate task. I was, quite simply, asking them to dredge up what they might well have preferred to forget. For my part, I still remember distinctly the dismay and hurt I felt on reading John Simon's review (page 42) buc after some weeks I began to see the funny side of it, and not much later was quoting it freely. I hoped to discover that this attitude prevailed among my betters and peers. I was not disappointed. The replies rolled in and much encouragement with them. Some sent several cuttings tochoosefrom. Justafewdidn't reply. Otherscouldn'tremember,but urged me to research. I then realized how big a task I had undertaken. To do credit to the generosity of my contemporaries I felt I must, in fairness, demonstrate how their predecessors had fared similarly: how adverse criticism had been visited on one and all, even the most legendary. So I set to work, researching back to the earliest sources of comment on actors and their art. Critics as a formally appointed bodyof men and women whose job is to express a viewof what is happening in the theatre are acomparatively recent phenomenon: theydidn't really get going until the eighteenth century. But remove the capital 'C\ the formal designation, and it turnsout that from the very beginning the audience has contained people who insist upon making their reactions felt, both during and after the performance. A As Ralph Richardson said in an article fortheold Vic-We/IsMagazine, memberof the audience, if he's worth anything at all, when he gets home after a performance, will criticise the entertainment he has seen. It is in the nature of things that he should and it hasn't done him anygood if he does not.' In this sense we are all critics, and so it has been since the very beginning. Turns, I discovered, havebeen stoned bymanypeopledown theyearsforextremely varied reasons. Bad noticesgo back as far as acting itself. When Thespis, the Greek poet who founded our profession, made history by stepping outof thechorus to impersonateoneof thecharacters in the story that was being told, not everyone greeted this brilliant departure with the enthusiasm it deserved. (I wonder what prompted him to take thisrevolutionary step? Even today, directors complain that actors always want to improve their parts: but we have an ancient precedent and the instinct remains strong!) When Thespis brought his invention to Athens around 560BC, Solon, the lawgiver, denounced it as a dangerous deception. This was more than a personal view: it was the expression of a deep social anxiety over the representation of godlike qualities by a mere man. On this first confrontation, however, the critics were overridden by the success of the enterprise. (And not for the last timeeither.)By 543BC thepracticewasso well established that a competition in tragic acting was held in Athens, and Thespis, now an old man, was awarded first prize. At this early stage all the parts in a play were performed byone man, usually the author. Aeschylus, the great actor-dramatist, then added a second actor to the cast in his plays, Sophocles added a third, and so the profession was established. From that dawn until the present day it has continued in the teeth of a daunting opposition, ranging from the intellectual and civic leadersofclassical antiquity through the saints and Church Fathers to the Puritan opposition of relatively modern history.