New York Amish: Life in the Plain Communities of the Empire State PDF

Preview New York Amish: Life in the Plain Communities of the Empire State

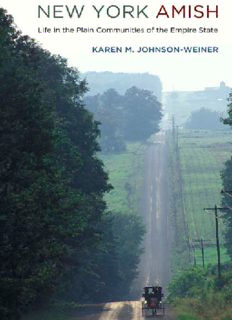

New York Amish Karen M. Johnson-Weiner New York Amish Life in the Plain Communities of the Empire State Cornell University Press Ithaca and London Copyright © 2010 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2010 by Cornell University Press Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Johnson-Weiner, Karen. New York Amish : life in the plain communities of the Empire State / Karen M. Johnson-Weiner. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-4518-7 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Amish—New York (State) I. Title. F130.M45J64 2010 289.7'3—dc22 2009050339 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally re- sponsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent pos- sible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Preface vii 1 Who Are the Amish? 1 2 Cattaraugus and Chautauqua Counties: Twentieth-Century Amish Pioneers in Western New York 30 3 St. Lawrence County’s Swartzentruber Amish: The Plainest of the Plain People 52 4 From Lancaster County to Lowville: Moving North to Keep the Old Ways 78 5 The Mohawk Valley Amish: Old Order Diversity in Central New York 100 6 In Search of Consensus and Fellowship: New York’s Swiss Amish 122 7 On Franklin County’s Western Border: New Settlements in the North Country 141 8 The Challenge of Amish Settlement 162 9 Amish Settlement in New York: For the Future 178 Appendix A Existing Old Order Amish Settlements in New York 185 Appendix B Extinct Old Order Amish Settlements in New York 187 Appendix C Amish Divisions 188 Appendix D Amish Migration to and from New York 189 Notes 191 Bibliography 211 Acknowledgments 219 Index 221 v Preface When I first visited an Amish home more than twenty years ago, I did not know quite what to expect. I worried about what to wear. I had a vague notion that I would meet a stern, biblical-looking patriarch who would address me in archaic English while his neat but silent wife stood behind him. I assumed that the children would be seen but not heard. I looked forward to a people whose lifestyle was somehow slower, more natural, more satisfying, and less hypocritical than my own. I expected religious paragons, a people closer to their faith—“a little house on the prairie” come to life. The reality was not at all what I had imagined, but I have not been disappointed. Although I heard no “thees” and “thous” and discovered that Amish children could be every bit as naughty as my own, I did find a people committed to a way of life that makes them seem like “strangers and pilgrims” (1 Peter 2:11), in the world, but not of the world. In their at- tempt to establish and maintain “redemptive communities,” the Amish cherish tradition and family, are wary of progress, and interact with each other in unique ways to create a culture very different from that of their non-Amish neighbors. In the twenty-five years since that first visit, I have continued to be fascinated by the Amish and their ability to maintain distinct cultural, religious, and linguistic practices despite strong pressure to assimilate. My own German-speaking ancestors were English-speaking within a generation after their arrival, yet Amish children today continue to learn German as their first language. Dressed in archaic fashion and carefully choosing the technology they will use, members of Amish communities interact with the modern world and hold their own. From small roadside stands in rural St. Lawrence County, to Amish goat farms in the Finger vii preface Lakes region, to the “Amish Market” in downtown Manhattan, today’s Amish are changing the face of the Empire State. Although the first Amish settlers came to the state in the early nine- teenth century, it took over one hundred years for the next group of Amish to arrive, and twenty-five more years for a third settlement to begin. Since 1975, however, the Amish population in New York State has grown rapidly, and there are now more than twenty-five New York Amish settlements. Twelve of these are less than ten years old. Writing from Poland, New York, to the Lancaster County, Pennsylvania-based Amish publication the Diary, one Amish woman noted with surprise that the “migration list” revealed that seventy Amish families had moved to New York in the previous year. “There are new areas filling up all around us,” she asserted.1 Many New Yorkers do not understand their new Amish neighbors. For example, I am often asked whether the Amish are Christian. Others ask whether they are “some kind of cult” and whether they are related in some way to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the Mormon Church). Many see the Amish as quaint, without realizing the depth of their commitment to living their faith. My intention in this book is to introduce the Amish to their non- Amish neighbors and to highlight the diversity of Amish settlement in New York State and the contribution of New York’s Amish to the state’s rich cultural heritage. So that readers can better understand where the Amish come from and their relationship to other Christian groups, the first chapter explores the origins of the Amish in the religious confronta- tion and political upheaval of the Protestant Reformation and discusses contemporary Amish lifestyle and practices. Chapter 2 begins the discus- sion of Amish settlement in New York by looking at the oldest surviving New York Amish community, the settlement in the Conewango Valley, which began in 1949. Each subsequent chapter explores the history of different Amish groups that have come to New York, looking to the past to help explain why they have chosen to settle in the Empire State. Although the need for farmland is a common denominator, each group provides a lens through which to explore issues that have helped shape the Amish world. The Lowville Amish, for example, are descendants of Lancaster County Amish who left Pennsylvania rather than submit to new state laws regarding education. The Ohio Amish who have settled in the Mohawk Valley have been shaped by internal struggles over the behavior of young people, while the Troyer Amish of the Conewango viii preface Valley evolved in response to internal disagreements over excommuni- cation and shunning. In describing life in different Amish settlements, this book also illus- trates the diversity of the Amish world. We tend to talk about the Old Order Amish as if they were all the same when, in fact, there are many different kinds of Amish. Frolics (work parties), weddings, dress, and buggy styles vary from community to community. Even within New York State, one Amish group may know little about the others and be surprised at their practices. Each chapter provides a snapshot of life in particular Amish settlements. I focus on different regions of Amish settlement across the state, begin- ning with the Amish churches in Chautauqua and Cattaraugus Counties in the west, and then looking at the diverse settlements of the Mohawk Valley in the east and the St. Lawrence River Valley in the North Country. The different congregations in these regions range from the most con- servative to the most progressive. In looking at the interaction of Amish communities in particular geographic settings, we can see how the differ- ent ways in which the Amish realize core values shape their adjustment in new environments. We can also see how these differences in Amish practice affect the interaction between Amish groups and between Amish settlements and their non-Amish neighbors. Two Amish groups have established multiple settlements in differ- ent regions of New York. Chapter 3 looks at the Swartzentruber Amish, perhaps the most conservative of all Amish groups. Since the first Swartzentruber Amish arrived over thirty years ago, they have estab- lished settlements in several regions of the state. Chapter 6 explores New York’s Swiss Amish, who are historically and culturally different from other Amish groups. There are now three related Swiss settlements. As Amish settlers from one church group move into different regions, we can see the impact of place on religious practice. Doing research within Old Order communities is not always easy. I have found that the Amish are suspicious of questionnaires and surveys and generally decline to take part. They favor personal interaction, but they generally do not permit themselves to be photographed, recorded, or videotaped because they believe that these technologies violate the commandment against the making of graven images.2 While I took most of the photographs in this book, most of the pictures of Amish children or adults were taken by others who have a different relationship with the Amish than I do. ix

Description: