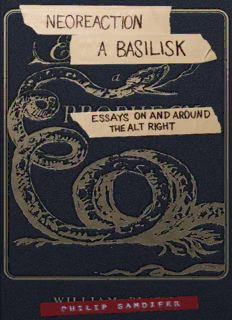

Table Of ContentNeoreaction a Basilisk

Essays On and Around the Alt-Right

Philip Sandifer

Copyright © 2017 Philip Sandifer

“No Laws for the Lion and Many Laws for the Oxen is Liberty” © 2017 Philip Sandifer and Jack Graham

Published by Eruditorum Press

All rights reserved.

All images are either public domain or used under the principle of fair use.

To the ghosts and the witches

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, this book would not exist were it not for David Gerard,

to whom it was basically serialized in e-mail as I wrote it, and who performed

the original copyedit on the manuscript (Alison Jane Campbell has done a

second pass since). David was an invaluable resource in pointing me towards the

sources I needed to make the argument, hone the jokes, and generally making

this entire mad caper work.

Thanks also to Jack, Sam, Jane, and Alex for podcasting about the book

with me and giving me a variety of insights that helped in fine-tuning it, and to

Veronica for her helpful comments on some of the early sections. Also thanks to

Emily Stewart for her help on “My Vagina is Haunted,” and to James Taylor for

his usual brilliance on the cover.

The book was also improved and refined (as well as promoted) by the many

people who reviewed and talked about the manuscript during the Kickstarter,

some sympathetically, some not so much. Particular thanks to both Nick Land

and Eliezer Yudkowsky, who fell on opposite sides of that divide.

Speaking of whom, although many of the sources that shaped the book are

obvious from reading it, one important one is not. A major push in writing it was

Park MacDougald’s fine essay “The Darkness Before the Right,” which

introduced me to the bewildering rabbit hole that is Nick Land. A nod also to

Kieron Gillen, who linked MacDougald’s piece on Twitter; this is all technically

his fault.

Finally, my profound thanks to the 708 Kickstarter backers who made this

book possible. My gratitude is immense, and I hope it lives up to your

expectations.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Neoreaction a Basilisk

The Blind All-Seeing Eye of Gamergate

Theses on a President

No Law for the Lions and Many Laws for the Oxen is Liberty: A Subjective

Calculation of the Value of the Austrian School

Lizard People, Dear Reader

My Vagina is Haunted: Notes on TERFs

Zero to Zero: A Final Spin Around the Shuddering Abyss at the Heart of All

Things

Introduction

When I started this book, it was fun. An opportunity to connect some

philosophical ideas I’d been playing with, using some very silly rightwing

nutjobs who were nevertheless kind of interesting in a pathological way. The

book came in a joyful burst of late-night writing sessions, holed up in a candle-

lit room tapping away on my laptop, letting it all pour out of some strange and

liminal space I still don’t entirely understand.

Then everything went to shit, and suddenly a book about far-right nutjobs

stopped being quite as much fun and became somewhat more important.

This is not the first book on the alt-right to come out, although the main

essay was finished in May of 2016 and distributed to Kickstarter backers shortly

thereafter. But the bulk of books (and articles) on the matter so far have focused

on two questions that I admit to finding relatively uninteresting. The first is how

the alt-right came to happen. It’s possible to write intelligently on this topic as a

matter of history—David Neiwert’s Alt-America does an excellent job of tracing

the precise evolution of the far-right from the mid-90s to the present day, for

instance. But ultimately the question is fairly easy to answer: far-right

movements arise when the established order starts to crack. (This is also a good

time to weigh in on the terminology “alt-right,” which some have, not without

reason, criticized as masking the fact that we’re talking about a neo-nazi

movement. This is true, but equally, no iteration of far-right uprisings is entirely

like another, and while historical comparison is essential, so is having a specific

term for the enemy we’re fighting today. Alt-right has become the consensus

term, and there are higher priorities than complaining that we should have

picked a better one.) This does not mean, as far too many commentators have

suggested, that the people at Trump rallies making Hitler salutes are motivated

by “economic anxiety.” They’re motivated by racism. Duh. But their racism is

emboldened by a political order that visibly has no answers, is running just to

keep still, and not even managing that. The path to the mainstream that this

particular batch of racists took is worth documenting as a matter of historical

record, but the question invites missing the forest for the trees.

The cautionary tale in this regard is Angela Nagle’s appalling Kill All

Normies, which takes the jaw-droppingly foolish methodology of simply

reporting all of the alt-right’s self-justifications as self-evident truths so as to

conclude that the real reason neo-nazis have been sweeping into power is

because we’re too tolerant of trans people. From this spectacularly ill-advised

premise Nagle makes the inevitable but even worse conclusion that the obvious

thing to do is for the left to abandon all commitment to identity politics (except

maybe feminism which, as a white cis woman, Nagle has at least some time for).

This brings us to our second relatively uninteresting question, which is what

to do about the alt-right. In this case the answer is even easier and more obvious

than the first: you smash their bases of power, with violent resistance if

necessary. If you want a more general solution that also takes care of the factors

that led to a bunch of idiot racists being emboldened in the first place you drag

all the billionaires out of their houses and put their heads on spikes.

But the ease of answer reveals the deeper problem with “what’s to be done”

as an angle on the alt-right. We all know what’s to be done. Nazis have been the

go-to example for people arguing why sometimes violent resistance is necessary

for decades. But in the absence of a credible resistance that consists of more than

hashtags and an inexplicable propensity to take Louise Mensch seriously the

knowledge of what we should do is fairly useless. We’re not doing it, and I am

to say the least skeptical that screaming “for fuck’s sake, just bash the fucking

nazis’ skulls in already” for the next 350 pages would magically kickstart a mass

uprising.

Instead this book asks a different question: if winning is off the table, what

should we do instead? Because the grim reality is that things look really fucking

bad. Ecological disaster is looming, the geopolitical order is paralyzed, and

we’re not putting nearly enough billionaire heads on spikes to plausibly change

it. What then, is left?

This is not a question with straightforward answers. Straightforwardness is

for victors who get statues and ballads. The defeated operate from shadows and

hidden places, and the legacies they leave are cryptic and secret. This book

behaves accordingly, and there are limits to what I am willing or indeed able to

explain. Nevertheless, a brief overview.

There are seven essays in this book. They do not directly build on one

another or trace a single argument, and are united more by approach and

philosophical concerns than by topic per se. The main essay is the title piece, and

is the one I am most invested in allowing to stand on its own terms. That said, it

focuses on two specific strands of thought within the alt-right: their own

grappling with eschatology, and their roots in silicon valley tech culture (the

latter of which is probably the thing that most distinguishes them from previous

far-right movements). It takes as its starting point the work of neoreactionary

thinkers Mencius Moldbug and Nick Land, along with Eliezer Yudkowsky (who

is not on the alt-right but has a variety of interesting links to the topic). Its

ending point is considerably more oblique.

“The Blind All-Seeing Eye of Gamergate” moves the focus from the

philosophical and intellectual aspects of the alt-right to its blunt and practical

end of vicious online harassment campaigns, looking at, as the title suggests,

Gamergate, which in hindsight is increasingly clear as a watershed moment in

their ascent.

“Theses on a President” tackles the obvious topic. It does not analyze

Trump primarily in terms of the alt-right, but rather takes a psychogeographic

approach to him, treating him as a pathological condition of New York City. I

should note that it was written before the 2016 election, although the final three

theses have been revised in light of the outcome.

“No Law for the Lions and Many Laws for the Oxen is Liberty” is first and

foremost an opportunity for me to finally collaborate with my dear friend and

colleague at Eruditorum Press, Jack Graham. It offers a more historically rooted

perspective on it, looking at its long roots, both intellectual and material, the

Austrian School of economics.

The next two essays—“Lizard People, Dear Readers” and “My Vagina is

Haunted”—are not about the alt-right per se, but instead offer insights about the

phenomenon by looking at topics that are, in their own way, analogous. The

former looks at the conspiracy theories of David Icke to muse on the value of

crackpots and nutjobs. The latter looks at TERFs, a group of nominal feminists

whose activism focuses largely on objecting to the existence of transgender

women, and offers the book’s most direct answer to the question “what do we

do?”

Finally there is “Zero to Zero,” which returns to the concerns of the first

essay to look at Peter Thiel, the moneyman behind both Eliezer Yudkowsky and

Mencius Moldbug, seeking to come to some final insight about our onrushing

doom. I hope the book that results from juxtaposing these seven works provides

some entertainment and insight while you wait for extinction.

-Phil Sandifer, November 26, 2017

Neoreaction a Basilisk

I.

“Do you know that every time you turn another page, you not only get us closer to the monster at the end of

this book, but you make a terrible mess?”—Grover, The Monster at the End of This Book

Let us assume that we are fucked1. The particular nature of our doom is up

for any amount of debate, but the basic fact of it seems largely inevitable. My

personal guess is that millennials will probably live long enough to see the

second Great Depression, which will blur inexorably with the full brunt of

climate change to lead to a massive human dieback, if not quite an outright

extinction. But maybe it’ll just be a rogue AI and a grey goo scenario2. You

never know.

There are several reactions we might have to this realization, and many of

us have more than one. The largest class of these reactions are, if not

uninteresting, at least relatively simple, falling under some category of self-

delusion or cognitive dissonance. From the perspective of 2017 the eschaton

appears to be in exactly the wrong place, such that we’re either going to just

miss it or only see the early “shitloads of people dying” bits. And even if it is

imminent, there is no reason to expect most of us to engage with it differently

than any other terminal diagnosis, which is to say, to minimize the amount of

time we spend consciously dying. Indeed, my polite authorial recommendation

would be to do exactly that if you are capable, probably starting by simply not

reading this.

Hmm. Well, no one to blame but yourself, I suppose. A second category,

marginally more interesting, is what we might call “decelerationist” approaches.

(The name is a back formation from the accelerationists, more about whom

later.) These amount to attempts to stave off the inevitable as best as possible,

perhaps by attempting to reduce carbon emissions and engage in conservation

efforts to minimize the impact of the anthropocene extinction or by writing

fanfic to conjure the AI Singularity or something. These efforts are often

compatible with active self-delusion, and in most regards the current political

system is a broad-based coalition of these two approaches. But the

decelerationist is at least engaged in a basic project of good. I tend to think the

project is doomed (although being wrong about that would be lovely), however,

and this work is on the whole aimed at those who similarly feel somewhat

unsatisfied with decelerationism.

From this point the numbering of categories becomes increasingly

Description:A software engineer sets out to design a new political ideology, and ends up concluding that the Stewart Dynasty should be reinstated. A cult receives disturbing messages from the future, where the artificial intelligence they worship is displeased with them. A philosopher suffers a mental breakdown