Preview NEA arts

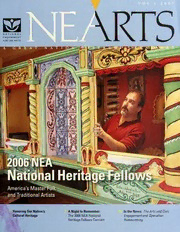

ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS America's and Traditional Artists Honoring Our Nation's A Nightto Remember: In the News: The Arts and Civic Cultural Heritage The 2006 NEA National Engagementanti Operation Heritage Fellows Concert Homecoming NEAARTS Honoring Our Nation's Cultural Heritage NEA National Heritage Fellowship Program "The class of 2006." That’s the way Mavis Staples In the end, a slate is described herselfand the other distinguished recipients recommended to the ofour nations highest form offederal recognition of National Council on folk and traditional artists, the NEA National Heritage the Arts and the Fellowships. In September 2006, a group of 1 1 musi- National Endowment cians, craftspeople, dancers, storytellers, and cultural for the Arts Chairman conservators came to Washington, DC to be honored for final approval. for their lifetimes ofcommitment to creative excellence The process culmi- and cultural heritage. Admission to this class is no small nates in September accomplishment. These artistsjoined such luminaries as with a banquet in the B.B. King, Bill Monroe, Ali Akbar Khan, Michael Flatley, Great Hall ofthe FolkandTraditionalArtsDirector and Shirley Caesar as honorees. Library ofCongress, an BarryBergeywith2006NEANational Each year a panel ofexperts spends four days dis- Heritage FellowMavisStaplesat awards ceremonyon cussing thousands ofpages ofmaterials and reviewing theawardsceremonyandconcert Capitol Hill, and a hundreds ofmedia samples supporting the more than rehearsal atthe Music Centerat public concert. This Strathmore.PhotobyTomPich. 200 nominations received from the American public. year the concert was held for the first time at the new Music Center at Strath- NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE ARTS more in nearby Bethesda, Maryland. DanaGioiaChairman JamesBallinger The events in 2006 marked the 25th year that these BenDonenberg fellowships were awarded, and more than 325 artists and MakotoFujimura David H. Gelernter groups have now been recognized as NEA National NATIONAL Chico Hamilton Heritage Fellows. With the generous support ofDarden ENDOWMENT MarkHofflund FOR THE ARTS Joan Israelite Restaurants and Darden Restaurants Foundation, we CharlottePowerKessler plan to celebrate the 25th anniversaryin 2007-8 with Agreat nation Bret Lott deservesgreatart. JerryPinkney special concerts, tours, exhibitions, publications, and FrankPrice GerardSchwarz media programs around the country. TerryTeachout The cumulative history ofthe NEA National Heritage Dr. KarenLiasWolff Fellowships provides a striking portrait ofour nation. EX-OFFICIO Bess Lomax Hawes, the NEA Folk Arts Director who AppointmentbyMajorityandMinority conceived and initiated the program, perhaps said it best: leadershipofsixMembersofCongresstothe Councilispendingforthe 110thCongress. “Ofall the activities assisted by the Folk Arts Program, these fellowships are among the most appreciated and NEAARTSSTAFF applauded, perhaps because they present to Americans PauletteBeete Editor Don Ball ManagingEditor a vision ofthemselves and oftheir country, a vision BarryBergey Contributor Beth Schlenoff Design somewhat idealized but profoundly longed for and so, in significant ways, profoundlytrue.” ONTHECOVER: 2006NEANational HeritageFellowCharlesM. Carrilloworkingona Barry Bergey newaltarscreenforSantaMariade la PazChurch inSanta Fe.Photo byPaul Rhetts,courtesyofwww.nmsantos.com. Director, Folk and TraditionalArts 2 — NEAARTS A Remember Night To NEA The 2006 National Heritage Fellows Concert A celebration was underway applause from the audience. as members ofNew Orleans’s As Spitzer introduced Treme Brass Band paraded Tewa linguist and storyteller through the aisles ofthe Esther Martinez, he said, Music Center at Strathmore. “Fanguage is the music of the The audience enthusiastically storyteller.” Accompanied by joined in,jumping to its feet her daughter and grandson, and clapping hands in time Martinez taught Spitzer to say with the bass drum as the a few words in Tewa and band mounted the stage. So shared passages from her began the 2006 NEA National favorite stories. Heritage Fellows concert. Tight harmonies and sonic Produced in partnership fingering are the hallmarks with the National Council for ofbluegrass and gospel artist the Traditional Arts, the Doyle Fawson who, with his annual concert is the culmi- band Quicksilver, wowed nation ot the new Fellows’ the crowd in the program’s awards week in Washington, TheTremeBrassBandopenedthe2006NEANational Heritage second half. Dressed in a Fellowsconcertwitha paradethroughtheconcerthall aisles. DC. rlhe Music Center was a PhotobyTomPich. vibrant yellow suit, kumu first-time host for the 2006 hula George Na’ope brought concert, which featured performances and craft demon- Hawaii to the mainland, playing ukulele with his band strations by the Fellows. after a traditional dance performance by some ofhis Emceed by Public Radio International radio host students. Nick Spitzer, the concert’s first act included cuatro Master santero Charles Carillo shared the stage with maker and player Diomede Matos, who performed with his blue-tinged portrait ofSan Rafael. Bess Fornax his students, the Camacho Brothers, and his son Pucho; Hawes honoree Nancy Sweezey also shared the stage and blues pianist Henry Gray, backed by a four-piece with a slideshow ofphotos from her decades long career band and demonstrating his legendary barrelhouse as an advocate for the folk and traditional arts. style. The evening’s final performer, gospel and rhythm- Invoking a centuries-old family tradition, Finnish and-blues artist Mavis Staples, kept things up-tempo as kentele player Wilho Saari demonstrated his skill on the Spitzer called the 2006 class ofNEA National Heritage 36-string lap harp. Saari’s great-great-grandmother Fellows to the stage for a group bow. The concert ended “Kantele Kreeta” originally popularized the instrument as it began, with the audience applauding, dancing, and in 19th-century Finland. hollering for more. Welcomed to the stage byher singing granddaughters, In the pages that follow, a briefbiography ofeach Haida traditional weaver Delores Churchill also Fellow is presented along with an excerpt from inter- appeared in the program’s first half. Churchill noted that views that the NEA has conducted with the artists. Read she had been a bookkeeper until age 45. “Then I became full versions ofthe interviews at www.nea.gov/honors/ insane and became an artist,” she recalled, prompting heritage/Heritage06/NHFIntro.html, 3 I NEAARTS CHARLES M. CARRILLO Santero (Carver and painter ofsacred figures) Santa Fe, New Mexico Atrained archaeologist, Charlie Car techniques ofsanteros, and why he rillo developed his interest in santeros remains compelled by his craft. during a research project in the late 1970s. He explained, “As I read NEA: What special skills do you think through documents I was fascinated santeros need? with all the references to santos.... CHARLES CARRILLO: You need the decided one day to paint an image of desire to understand traditions. Some [Santa Rosa de Lima] based on a his- ofthe santeros in the past weren’t toric picture I had seen ofher from great artists. The artwork is some- New Mexico." In 1980, Carrillo made times very crude. But they had a deep his first appearance as a santero at feeling for what they were trying to New Mexico’s Spanish Market, a bi- impart with their images. annual traditional crafts market. This is not just about art, it’s about Carrillo’s work is in the permanent a people’s philosophy. It’s about a peo- collections ofmuseums, including the ple’s way oflife, a people’s outlook on Smithsonian Museum ofAmerican NuestraSerioradelPueblitodeQueretaro life. The santos express not only the History in Washington, DC, the (OurLadyoftheVillageofQueretaro)bultoby hopes and dreams ofpeople, but also Museum ofInternational Folk Art in CharlesM. Carrillo. CollectionofPaul Rhetts the sadness. We need our saints for and BarbeAwait.PhotobyRon Behrmann, Santa Fe, and the Denver Museum of courtesyofwww.nmsantos.com. the good things in life and the Art. His honors include the Lifetime tragedies. The total package. And in Achievement Award at the Spanish Market and the New Mexico there’s a saint for everything. Museum ofInternational Folk Art’s Hispanic Heritage Award. NEA Are the techniques being used today differentfrom In this excerpt from an NEA interview, Carrillo spoke the past? about what it takes to be a master artist, the traditional CARRILLO: I’ve been the one pushing for the re-intro- duction oftraditional pigments and other traditional elements. Twenty-five years ago at the Spanish Market, very few people were using natural pigments, natural homemade varnishes, natural production methods of hand daubing the wood, or usingcottonwood root for carving, and so on. Now it’s the norm, the standard. NEA Why do you continue to be so invested in this work? CARRILLO: It’s a passion. I look forward every morning to getting up and doing what I do. Notjust the making, but the research, too. I love to find new historic images that inspire me to do newthings. I love to teach. CharlesM.Carrilloshowshisworkduringthe2006NEANational Teaching about the santos and New Mexico historyis HeritageFellowsconcert. PhotobyTomPich. a passion. NEAARTS DELORES CHURCHILL E. Haida traditional weaver Ketchikan, Alaska Delores Churchill is a Fiaida master weaver ofbaskets, hats, robes, and other regalia. Using such materials as spruce root, cedar bark, wool, and natural dyes, she creates utilitarian and ceremonial objects ofunmatched beauty and cultural significance. Churchill learned these skills from her mother, Selina Peratrovich, a nationally recognized master weaver. Peratrovich asked her daughter to burn her baskets for the first five years ofthe apprenticeship. “I am well known for my baskets,” Peratrovich told her daughter. “Ifyou sayyou learned from me, you better be good.” Churchill’s honors include a Rasmuson Foundation Distinguished Artist Award, the Governor’s Award for the Arts, and an Alaska State Legislative Award. She continues to teach young people the knowledge and skills related to the weaving tradition, observing: “As long as Native art remains in museums, it will be AseaweedbasketbyDeloresE. Churchill. PhotocourtesyofDelores thought ofin the past tense.” E. Churchill. In this excerpt from an interview with the NEA, Churchill reminisced about how her children learned to and sit byMother and watch herweave. Then one day weave and teaching others Tlingit weaving. she came in with a basket and put it in front ofmy motherwho asked, “Who made that nice basket?” And NEA: Did your children April said, “I did, Grandmother.” From then on, Mother learn weaving in the started teaching her. traditional way? DELORES CHURCHILL: What advice do you have foryoung basket makers? Yes. In fact one time CHURCHILL: It takes years before one can do a basket like when [mydaughter] the ones I see in the museums. It’sjust like ballet. My April wasvisiting my daughter took ballet. She wasn’t allowed to get into toe mother, she said, shoes foryears. She had to learn all the steps and all the “Grandmother, I would moves before she could get into toe shoes. It’s the same like to learn to weave,” thing with basketry. Before you can do an artistic piece and Mother said, “No, there are years when you’rejust learning to prepare your no, mydear. You’ll neg- materials. Preparingyour material is actuallythe most lectyour housework important part ofit. When the university asked me to and your children ifyou teach an evening class because there were so many start weaving so, no, you DeloresE.Churchill demonstrates people wanting to learn to do basketry, my mother told Haida basketweavingduringthe shouldn’t do that.” So 2006NEANational HeritageFellows me, “You’re not ready.” For the next two years all I did April wouldjust drop in concert.PhotobyTomPich. was material preparation. 5 NEAARTS HENRY CRAY Blues piano player and singer Baton Rouge, Louisiana Baton Rouge, Louisiana, blues pianist Henry Grayhas performed for more than seven decades, having “played with every- body from the Rolling Stones to Muddy Waters.” He has more than 58 albums to his credit, including recordings for the legendaryChess blues label. Gray helped to create the distinctive sound ofthe Chicago blues piano while playing in Howlin’ Wolf’s band in the 1950s before returning to Louisiana in the 1960s where his big, rollicking sound became part ofthe region’s “swamp blues” style. Having received a Grammy nomination and four W.C. Handy nominations, Gray continues to tour as a soloist and with his band Henry Gray and the Cats. Gray spoke with the NEA about the start ot his long career and the future ofthe blues. HenryGraytakestheaudienceonatourofthe"swampblues"he NEA Tell me a little bit aboutwhen you started learning helpedcreateduringhisperformanceatthe2006NEANational HeritageFellowsconcert.PhotobyTomPich. to playthe piano. HENRY GRAY: When I was a child mygrandmother bought me an old piano. I started out playing a harmon- NEA: Do you see any challengesto keeping the blues ica when I was about six or seven, but I didn’t like that tradition alive? thing. I liked my piano and I just started to play. GRAY: The blues are here and are going to be here to stay. I grew up in rural Louisiana, a little town called Now they’ve got a whole lot ofthis stuff, the rap and all Alsen. I doubt there were 100 people there. There was a that, but that’s not like the blues. The blues have been lady, Ms. White, who had a piano and starting when I here and are always going to be here. was seven or eight I would go by there. She played the blues and showed me a whole lot ofstuffon the piano. I NEA What advice do you have foryoung artists who are was quick to learn. All I wanted was to get the funda- learning piano blues? mentals ofit and learn the keys. After learning that, 1 GRAY: Keep at it. Just keep at it because you’re not going had it made. to learn it overnight. There’s too much going on with it You know, my daddy whupped me a couple oftimes for you to learn it overnight. You just have to keep at it because I’d skip school to go over to Ms. White’s to play and keep going. You’re going to make a lot ofmistakes, piano. I didn’t want to go to school. I just wanted to play but you’ll correct them. the piano. 6 — NEAARTS DOYLE LAWSON Gospel and bluegrass singer, arranger, bandleader Bristol, Tennessee — Raised in a musical household his parents were part of NEA: Do you have any advice foryoung gospel or an a cappella trio and later his father formed a quartet bluegrass musicians? Doyle Lawson decided to be a professional musician as LAWSON: I don’t thinkthere’s any one for-sure answer. a teenager, becoming proficient on the mandolin, banjo, Sometimes some things work out and sometimes they — and guitar. Before forminghis own group Doyle Lawson don’t. The one thing I can say is that ifyou trulybelieve — and Quicksilver in 1979, Lawson played with bluegrass thatyour mission in life is to play this music, then stay legends Jimmy Martin, J.D. Crowe, and the Country the course. You’ll have to endure the hardships along Gentlemen. He has appeared on nearly40 albums, many with the good times, and there will be hard times. ofthem with his own band. Although Lawson’s band has numerous recordings ofthe classic bluegrass repertoire, the group is best known for his stunning gospel vocal arrangements, which resulted in a renaissance oftight harmony bluegrass singing. For several years, Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver have received the International Bluegrass Music Association’s Vocal Group of the Year Award. In a conversation with the NEA, Lawson talked about his music, shared some advice for young musi- cians, and revealed why he’s kept singing for more than 40 years. NEA: You play both religious and secular music, correct? DOYLE LAWSON: I started offplayingjust bluegrass Doyle Lawson(left)andhisbandharmonizeduringthe2006NEA National HeritageFellowsconcert.PhotobyTomPich. music. But gospel music has always been an integral part ofbluegrass as far back as the man we call “the Father of Bluegrass,” Bill Monroe. He had the Bluegrass Boys and NEA:What has keptyou performing through the years? the Bluegrass Quartet and theyalways played a fair LAWSON: I love the sound ofmusic and I love to sing amount ofgospel. And that carried right on down harmony. That’s my thing, putting four or five voices through the Stanley Brothers, Flatt and Scruggs, all the together. To me there’s nothing anysweeter to hear than earlybluegrass pioneers. Gospel music was still a part of a church choir singing or a church congregation with that. Gospel was not only a part ofbluegrass, but part of everybodylifting theirvoice up in song and praise. the country world, too. When I came along, I introduced There’s a beauty to that and a feeling like no other. a lot of different songs new to the world ofbluegrass. 7 NEAARTS ESTH ER MARTI N EZ Native American linguist and storyteller Ohkay Owingeh, New Mexico Known as P'oe Tswa (Blue Water) and Kobe (Aunt) who spoke eloquently ofMartinez’s contributions and Esther, master storyteller EstherMartinezwas a much presented her with a plaque. Chairman Dana Gioia beloved tradition bearerofthe Tewa people. New Mexico noted upon learning ofher passing: “New Mexico and state folklorist Claude Stephenson succinctlysummed up the entire country have lost an eloquent link to our past. hercontribution to Tewa culture: “She serves as the rock We can find solace in remembering her lifelong com- that has firmlyanchored the ancient and the timeless mitment to keeping her culture alive and vibrant. Our — stories ofthe people to the present and guaranteed their prayers are with Esther and her family and all those survival for the pueblo people ofthe future.” who have come to know and love her.” Martinez was raised by her grandparents in San Juan Congress has since passed the Esther Martinez Pueblo, New Mexico (now called Ohkay Owingeh), Native American Languages Preservation Act of2006. where she was immersed in the pueblo’s communal Introduced by U.S. Representative Heather Wilson (New traditions. As an adult she became an advocate for the Mexico-lst District), the hill authorizes the Department conservation ofthe Tewa language. Tier efforts included ofHealth and Human Services to award competitive storytelling, teaching, and the compilation ofTewa grants to establish native language programs for students dictionaries for each ofthe six Tewa dialects. “When under the age ofseven and their families to preserve the my grandfather said something that I didn’t know,” indigenous languages ofNative American tribes. Martinez said about creating the dictionaries, “1 would ask him and I would write it on a paper. It took me a long time.” In her late 70s, Martinez traveled through- out the U.S. with Storytelling International, for the first time telling her traditional stories in English to non-Tewa audiences. Martinez eagerly embraced her role as a tradition bearer, especially among the pueblos’ young people. She said, “People still come to my house want- ing help with information for their college paper or wanting a storyteller. Young folks from the village, who were once my students in bilingual classes, will stop by for advice in traditional values or wanting me to give Indian names to their kids or grandkids . . . Ihis is my po’eh (my path). I am still traveling.” Martinez was killed in an auto accident in September 2006 after attending the NEA National Heritage Fellowships ceremony in Washington, DC. During the awards ceremony on 2006NEANational HeritageFellowEstherMartinezwithdaughter Josie,NEAFolkandTraditionalArtsDirectorBarryBergey(left),and Capitol Hill earlier that week, she wasjoined by U.S. NEAChairman Dana Gioia(right)atthe LibraryofCongressbanquet. Representative Tom Udall (New Mexico-3rd District), PhotobyTomPich. 8 NEAARTS DIOM EDES MATOS Cuatro (10-string Puerto Rican guitar) maker Deltona, Florida Diomedes Matos has been referred to as the “master’s master” cuatro maker. The cuatro, a distinctive 10-string guitar known as the national instrument ofPuerto Rico, is played byjibaro musicians from the mountainous inner regions ofthe island. Matos was surrounded by instrument makers where he grew up in the Puerto Rican village of Camuy. He built his first guitar at age 12, later mastering construction techniques for several traditional stringed instruments in- cluding cuatros, requintos, classical guitars, and the Puerto Rican tres. His instruments are in great demand; even popular singer Paul Simon asked Matos to build him an instrument and accompanyhim on the soundtrack for the Broadway show The Capeman. DiomedesMatos(left)showsoffoneofhishandmade cuatroswhile playingwithhisson Puchoatthe2006NEANational Heritage Matos has passed on his extensive knowledge to Fellowsconcert. PhotobyTomPich. future tradition bearers through programs such as the New Jersey Folk Arts Apprentice Program. He said, “I What reallyinspired me was a cuatro maker named like teaching even more than cuatro-making itself, espe- Roque Navarro. He passed awaysome years ago. I used ciallywhen I see a student’s progress and maturity.” to walk from my house to school every day and on the Matos spoke with the NEA way I’d see Mr. Navarro working on guitars and cuatros about becoming a cuatro maker in his workshop. One day, when I was about 10 years old, and shared his advice for young I was watching him from the fence in front ofhis house instrument makers. and he invited me in and showed me what he was doing. I knew from that first visit that’swhat I wanted to do. NEA Tell me a little bit about how you were attracted tothetradition NEA What advice do you have foryoung cuatro makers of making these instruments? and players? DIOMEDES MATOS: Myyounger MATOS: I always tell them to keep the tradition going, brother is a luthier [stringed- don’t lose this knowledge. And tryto do what I do— instrument maker], too. On my teach other people. Keep learning and become a teacher, mother’s side ofmy family there too. I also tell them to tryto be as best as possible. The — are a lot ofmusicians my uncles more they learn the better theyget. It’s a process that and my otherbrothers playguitar requires a lot ofpatience—don’t stop after making one and cuatro and they know how or two. Keep making cuatro after cuatro because the Acuatromadeby to workwith wood. They are DiomedesMatos. more experienceyou have the betteryou’ll become at it craftsmen, too. PhotobyRobertStone. and the better the finished products will become as well. 9 NEAARTS GEORGE NA’OPE \\ 11 Kumu hula (hula master) II Hilo, Hawaii George Na'ope'sfull name is George Lanakilakekiahiali’i are very interested in the culture. I’ve been telling them, Na’ope, which means “the protectorofthings ofHawai’i.” though, that while it’s wonderful that all these non- As a kumu hula, Na’ope has taken this charge quite Hawaiians are learning Hawaiian culture, they need to seriously for nearly six decades. “Uncle George,” as he is remember to learn their own culture as well. When known throughout the state, is recognized as a leading we [Hawaiians] became part ofAmerica, most ofour advocate and preservationist ofnative Hawaiian culture people forgot our ancient dances. worldwide. Na’ope was three when he first studied hula under his great-grandmother. He himselfhas been a teacher for nearly 60 years, passing down his knowledge ofancient hula, which is hula developed and danced before 1893. In 1964, Na’ope founded the Merrie Monarch Festival, an annual week-long festival oftradi- tional Hawaiian arts, crafts, and performances featuring a three-day hula competition. The state ofHawaii designated Na’ope a “Living Golden Treasure” in 1960. Na’ope spoke with the NEA about why he founded the Merrie Monarch Festival and about passingon the tradition to the next generation. Why did you feel there was a need forthe Merrie Monarch Hula Festival? GEORGE NA'OPl I felt the hula was becoming too modern and that we have to preserve it. [David] GeorgeNa'opewatchesoneofhisstudentsperformatraditional Hawaiiandanceduringtherehearsalforthe2006NEANational Kalakaua [king ofHawaii 1874-91, aka The Merrie Heritage Fellowsconcert. PhotobyTomPich. Monarch] brought the hula back to Hawaii and made us realize how important it was for our people. There was nothing here in Hilo, so I decided to honor Kalakaua NEA What isthe main messagethatyou thinkthatthe and have a festival with just hula. I didn’t realize that it hula and the chanting is conveying? was going to turn out to be one ofthe biggest things in NA'OPE: We must remember who we are and that our our state. culture must survive in this modern world. Ifyou love your culture you will teach tradition and the love ot Can you tell me a little bit aboutyourteaching? the hula. Teach it and share it and not hide it. I tell the NA'OPE: I’ve been teaching now for about 58 years. I’ve young people to learn the culture and learn it well, pre- taught in Japan, Guam, Australia, Germany, England, serve it so their children and their children’s children North and South America, and also in the Hawaiian can continue with our culture and that our culture will Islands. I’ve mostlybeen teaching in Japan because they live forever. 10