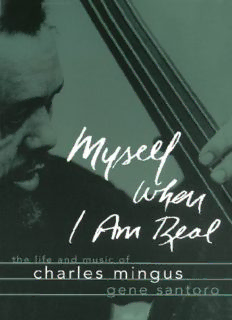

Table Of ContentMyself When lAmReal

Myself

xxh

OXPORD

UNIVERSITY PRESS

Th

x

The Lift and Music of

Charles Mingus

Gene Santoro

OXFORD

UNIVERSITY PRESS

Oxford New York

Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogota Buenos Aires

Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul

Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai

Nairobi Paris Sao Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw

and associated companies in

Berlin Ibadan

Copyright © 2000 by Gene Santoro

First published by Oxford University Press, Inc., 2000

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 2001

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Santoro, Gene.

Myself when I am real: the life and music of Charles Mingus / Gene Santoro.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-19-509733-5 (Cloth); ISBN 0-19-514711-1 (Pbk.)

I. Mingus, Charles, 1922-79. Jazz musicians—United States—Biography. I. Title.

M I .418.M45 526 200

781.65 '092—dc2I

[B] 99-046734

Boot design composition by Mark McGuny

Set in the Scala family of types

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 21

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

Contents

Preface vii

Introduction 3

Prologue: Better Get It in Your Soul 9

1 Growing Up Absurd 13

2 Black Like Me 25

3 Making the Scene 33

4 Life During Wartime 47

5 Portrait of the Artist 65

6 The Big Apple, or On the Road 87

7 Pithecanthropus Erectus 121

8 Mingus Dynasty 149

9 Camelot 177

10 The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady 209

11 One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest 243

12 Beneath the Underdog 277

13 Let My Children Hear Music 297

14 Changes 325

15 Don't Be Afraid, the Clown's Afraid, Too 353

Notes 385

Bibliography 391

Discography 401

Acknowledgments 425

Index 429

This page intentionally left blank

Prefacxe

CHARLES MINGUS, jazz's legendary Angry Man, lured me into writing this

book, relentlessly, seductively, finally, just as he'd gotten what he needed from

so many others while he was still alive.

I was a fan of his music; that was why I wanted to do the book at all. I admit

I didn't realize right away how lucky or right I was to choose Mingus as my bi-

ographical subject. The famed, even notorious composer-musician turned out

to be more fascinating and complicated than I'd guessed or hoped. His messy,

sprawling life, his endless quests, his acute self-awareness and persistent in-

volvement in so many facets of his time gave me a huge and ambitious canvas

to work on—the best of my life, as I soon began to find out.

The music drew me in, but the people and places hooked me. Once I was

into the couple of hundred interviews that help buttress this book, talking with

Mingus's families and friends and peers and colleagues and sidemen and be-

hind-the-scenes and in-the-know types, poking around the Mingus Archives at

the Library of Congress and the Institute for Jazz Studies at Rutgers Univer-

sity, digging up background material on this and that, it hit me like a sap

swung by a Raymond Chandler cop. The stories I knew, the tales widely retold

around the jazz world about this Gargantuan character were often myths.

Sometimes they distorted facts; sometimes they were just made up. Even the

true tales, I saw, offered only glimpses of the man's apparently hydra-headed

personality. And there were, I was finding, a lot of other tales not in the dossier.

Here's Charles Mingus, standard-issue thumbnail sketch. A fat, bristling,

vii

PREFACE

light-skinned black guy who busted people on the bandstand, who stopped his

shows midstream if a cash register rang or a fan or musician said or did some-

thing that set him off. If he was set off enough, he yelled at or lectured or

swung on or pulled a blade on the offender like he was the 240-pound wrath of

Zeus. Sometimes he connected. Sometimes he got backed down by somebody

with a gun or a knife. In a rage, he once tossed a $2,200 bass, one of his prized

instruments, onto a nightclub floor to shatter at a groupie's feet. In a similar

rage, he once yanked the tight-wound, wire-sharp strings out of a club piano

with his bare hands, and then shoved the piano down the stairs. He made a

movie of himself being thrown out of his downtown loft and carted off by the

New York Police Department. His mouth was always running off about racism,

about some kind of mistreatment or misunderstanding or persecution or lack

of recognition. He had a lot of fans who dug his shows. Important and influen-

tial critics and record company heads dug his music. He was rich. He died

broke. He'd erupt in volcanic passions for dim (if any) reasons. Erratic. Unpre-

dictable. Mood swings. Evil. His ego was a blimp, like the rest of him. He ate

like a pig. He loved fine wines and aged steaks and exotic cuisines. He chased

women constantly. Women, especially white women, adored him. He acted like

a pimp. He brooded. He didn't hang out. He talked nonstop. Everyone was

scared of him. He hated white guys. He was mean and hard and cheated people

and put his name on music he had others write. He was an endless self-pro-

moter. He always bragged he was one of jazz's greatest composers, the succes-

sor to Duke Ellington. He wrote some amazing stuff, he couldn't write a

standard pop tune, he couldn't read music or keep time, he was a bass virtuoso

but he was lazy. He always had an edge to him. He said a lot of things that

needed saying when nobody else was saying them. Maybe he was a genius and

maybe he wasn't. Nobody could play his music right. He made a big impact.

People liked him or hated him, avoided him or played with him. Sometimes—

a lot of times—they hated him and played with him. He was Jazz's Angry Man.

But, a lot of the people who actually knew him were saying, what about

Mingus? What about his devastating grin, his crackling electricity, the voice

that leaped yelping intervals, the charm, intelligence, humor, vulnerability, ver-

bal dexterity, flashes of insight, volatility, childishness, and sheer charismatic

pull we all felt and saw and loved in the complicated Mingus we knew? And the

stories would follow.

Meanwhile, I'd gone back to listen to Mingus music. I let its panoramic

sweep wash over me instead of going for my favorite fishing holes. And in the

process a nagging problem that wouldn't go away became the wellspring for

this book.

Here's the problem. Mingus music is overwhelming in its torrent of musi-

viii

PRE FACE

cal styles and psychological switchbacks and emotional punch, its tumble of

raucous gospel swing, luminous melodies, European classical threads, bebop

tributes, Mexican and Colombian and Indian music and sounds from any-

where and everywhere. He had incredibly sharp and open-minded ears, for a

violent, self-obsessed asshole who may have been a genius.

Genius. How else to explain all this huge sonic crazy quilt that is Charles

Mingus's art, and why it could, and still does, touch a lot of listeners?

So then, if all this stuff—these ridiculously diverse sounds full of majesty

and humor, buoyant joie de vivre and tidal waves of pain, lyrical yearning and

satiric edge all powered by a scary willingness to tackle any emotion head-on—

if all this stuff didn't come out of Charles Mingus, standard issue, where did it

come from?

As it turns out, for me that problem was irresistible. You're holding my so-

lutions, what made me write this book this way.

An old saw says biography is detective work. Out of stacks of witness testi-

mony and historical records and research, cross-referenced and cross-linked

and I hope not too crossed up, a historical narrative started to cohere around

this hero with more sides than a polyhedron. The plots and subplots of Charles

Mingus's life's drama unfold from before his birth on April 22, 1922, till just

after his death of Lou Gehrig's disease on January 5, 1979. Like him, like his

3OO-odd compositions and dozens of albums, they take in a lot of ground.

Creativity isn't necessarily straightforward in its dealings with the world. To

put it another way, no one has ever convinced me that the geniuses who have

the lasting human touch we call art are either monsters or role models, or even

that they should be. Shamans don't have to be horrible or nice. They just have

to work effectively in their surroundings, account for some of the planef s mys-

teries in ways the people they live among can understand.

What counts about artists is that they perceive reality differently. In any

clinical sense, they're not schizophrenics (although historically some of them

have been that too) because they produce something coherent in its own terms

that is valued by their communities—their art, their strikingly individual con-

tributions to human culture. Artists don't simply reflect their lives and times

like mirrors, but if they're worth anything they light some way we haven't seen

from quite that angle before. That takes a genius; otherwise everybody would

be doing it.

Mingus's strange and wonderful gift let him take his all-too-human self, his

tangle of desire and hope and need and strength, and translate it all into a spe-

cial place that others, too, can enter, in the magical way of art, when they listen

to his music. If s not a paradox to say that Mingus was most fully himself in his

music. It was his lamp unto the world.

iX