My Uncle Napoleon PDF

Preview My Uncle Napoleon

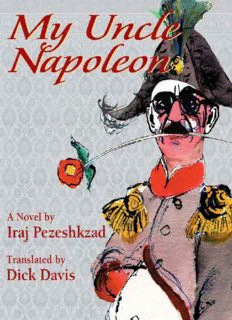

COPYRIGHT © 1996 MAGE PUBLISHERS COVER ILLUSTRATION BY ARDESHIR MOHASSESS COVER DESIGN BY ROHANI DESIGN, EDMONDS, WASHINGTON All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or retransmitted in any manner, except in form of a review, without written permission from the publisher. Mage and colophon are registered trademarks of Mage Publishers, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Pizish, Iraj. [Da’i-i Jan Napuli’un. English] My Uncle Napoleon / a novel by Iraj Pezeshkzad; translated from the Persian by Dick Davis. — 1st ed. I. Dick Davis, 1945- . II. Title. PK6561.P54D313 1996 891’.5533—dc20 eISBN 978-1-933823-49-2 Mage Publishers | www.mage.com | [email protected] | 202 342 1642 CONTENTS PREFACE PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS MAP PART ONE PART TWO PART THREE EPILOGUE GLOSSARY PREFACE THE EXISTENCE in Persian literature of a full-scale, abundantly inventive comic novel that involves a gallery of varied and highly memorable characters, not to mention scenes of hilarious farcical mayhem, may come as a surprise to a Western audience used to associating Iran with all that is in their eyes dour, dire and dreadful. And yet, in Iran itself, this novel is perhaps the most popular and widely known work of fiction to have been written in the country since the Second World War. Its wide acceptance by virtually all strata of society clearly belies the Western stereotype of the country as one that is single-mindedly obsessed, to the exclusion of all else, with religion and revolutionary revenge. My Uncle Napoleon occupies a unique place in Iranian cultural and literary history, because of both the affection in which it is held by its very large readership, and the self-image of the society which it portrays. In the early 1970s, a few years after its publication, the novel was made into one of the most successful television series ever to have been aired on Iranian television, and it is almost impossible for an Iranian to read the novel without the gestures, voices and faces of the actors who portrayed the characters being present in his or her mind. Certain of these portrayals, especially the actor Parviz Sayad’s portrayal of the roué with the heart of gold, Asadollah Mirza, and the late and much lamented Parviz Fanizadeh’s portrayal of Dear Uncle Napoleon’s servant Mash Qasem, have achieved the status of inviolable icons in popular Iranian culture. For a foreign reader perhaps the most intriguing question, beyond the enjoyment of the novel simply as the comic masterpiece which it undoubtedly is, must be, How accurate is this portrait of Iranian society? Perhaps the best way of answering this is to make an analogy with a couple of Western comic fictional characters and the novels in which they appear. P. G. Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster seems to his readers—British and non-British—to be quintessentially British in his foibles and absurdity, and there is no doubt that his portrait draws for comic effect on features of social behavior that are or have been highly specific to British society, and yet England is not populated with Bertie Woosters, even though particular English individuals or customs may occasionally evoke a laugh of recognition based on familiarity with the Wodehousian stereotype. In the same way Anita Loos’s Lorelei Lee (in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes) could only be an American character—her mannerisms and preoccupations tie her irrevocably to American society of the 1920s, and yet she is in her American way as unreal and as fantastic as Bertie Wooster is in his British way. Anita Loos and P. G. Wodehouse have used elements of their own societies and, by presenting them in the distorting mirror of farce, have produced versions of those societies that are recognizably based on features present in reality but are also outrageous exaggerations of those features—exaggerations that have been allowed, in the interests of facetious effect, to obliterate more mundane and less comically fertile aspects of social life. Iraj Pezeshkzad has done the same thing in My Uncle Napoleon. Any Iranian, and any foreigner who has more than a nodding acquaintance with Iranian culture, will recognize “real” and very culturally specific elements in the portraits and some of the situations present in the novel, but the Iran of My Uncle Napoleon is finally as “real” as Bertie Wooster’s England; it is a fictional fantasy that uses isolated features of the author’s social background in order to create the distortions and exaggerations of farce. This is not, though, to say that nothing in the novel corresponds with Iranian social reality, at least as it once existed; the book’s author has written elsewhere of how after the novel was published various individuals would ask him how he had known so intimately about the speaker’s father or grandfather, so convinced were they that this father or grandfather must have been the model for Dear Uncle Napoleon. My Uncle Napoleon is at least three kinds of novel—a love story, a farce, and a satire on local manners and preoccupations. As regards the first two categories the Western reader should have little trouble following what is going on. The narrator links the love story in which he is involved to both Iranian archetypes (Farhad and Shirin, Amir Arsalan and Farrokh Laqa) and Western ones (Romeo and Juliet, Paul and Virginie). The only aspect of this element that may give a young Western reader pause is the narrator’s insistence that he distinguish his love for Layli from any sexual feelings he may have, and his horror at his uncle Asadollah Mirza’s suggestion that he try to sleep with her—but this would have been the case also for many Western heroes created before the 1960s: the Paul of Bernardin de St. Pierre’s Paul et Virginie is even more determinedly chaste and pure in his intentions toward Virginie than Pezeshkzad’s narrator is toward his Layli. As a farcical comedy the novel has undoubtedly drawn on culturally specific features and phenomena (some of the situations are reminiscent of those used by the Iranian folk comic drama tradition of ru-hozi performance), but it also has clear parallels with the Western comic tradition; the authors of Tom Jones or Gargantua and Pantagruel or The Good Soldier Schweik would have had no trouble in responding to what was happening in much of My Uncle Napoleon, and anyone acquainted with the Western comic tradition will easily recognize in this novel familiar elements of farce and comic invention. While translating this work, however, I have been made aware of how unsympathetic some presently modish opinions in Western intellectual (more especially academic) circles are to farce; the stereotypical treatments of sexuality and sexual roles that are inherent in the genre, and the anarchic amorality that drives many farcical situations, are neither of them very amenable to sympathetic interpretation by current politically correct standards. This may well be political correctness’s loss, but if a Western reader feels uncomfortable with the farcical elements of the novel it is more likely to be for this reason than because the elements are unfamiliar in the Western tradition. Or to put it another way, if the reader can relish the farce in Tom Jones and Gargantua, the farcical elements in My Uncle Napoleon should prove equally accessible. Satire is the most culturally and temporally specific of all literary genres, and thus it tends to have the shortest shelf life and be the hardest to export. If a satire is to survive the age in and for which it was written, and to appeal to readers from other cultures, it needs to contain substantial elements beyond the satire of local institutions and individuals, as is the case with Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, for example, a work whose survival is probably due as much to its elements of fantasy and magical realism avant la lettre as to its satirical intentions. Certainly My Uncle Napoleon contains enough within its pages for it to make a broad appeal to readers quite unfamiliar with the specifics of Iranian cultural history, but equally certainly a knowledge of some features of that history will increase a reader’s comprehension and therefore enjoyment of what is happening in the novel. Much of the immediate historical background of the work can be gleaned from the novel itself, and the few details necessary for an understanding of the plot which the novel does not spell out are easily told. In 1941 the Allies (specifically the British and the Russians) invaded Iran, fearful that its government might declare for the Axis powers or that its oil reserves might fall into Axis hands. The country was occupied after a very brief campaign and the Allied forces stayed in Iran until the end of the war, forcing the abdication of the then shah (king) in favor of his son (who was the shah finally ousted by the Islamic Revolution of 1979). What is not apparent in such a summary outline of events is the cultural resonance of the invasion, and it is this cultural resonance which is the source of one of the chief comic devices of the novel, Dear Uncle Napoleon’s obsession with the hidden hand of the English. Since the early nineteenth century Iran had been an area squabbled over by the British and the Russians. The immediate reason for this was the presence of the British in India, and their desire to protect this jewel in the crown of the empire, and Russian expansion southward into the areas now occupied by the Moslem republics of central Asia. At the opening of the century the British and Russian borders in Asia were over two thousand miles apart; by the close of the century they were in places barely twenty miles apart. The Russians felt that the British had no business being in Asia at all, and the British feared a Russian threat to India. British and Russian agents and envoys both tried vigorously to control the shahs and tribal leaders of Iran and Afghanistan, and to influence them to favor their respective governments. Unfortunately for Iran, during most of the nineteenth century her government was severely strapped for cash and the country was in much need of both fiscal and social reform. Tribal discontent was an easy prey for foreign interference, and the ever-pressing need to raise money meant that successive shahs granted outrageous trading and development concessions to foreign businesses—particularly but not solely British—in return for (often not very much) cash on the table. Iran also went to war briefly with Britain (over Herat, in western Afghanistan), and twice went to war, with disastrous losses of territory as a result, with Russia. In 1907 Britain and Russia concluded an agreement at St. Petersburg by which Iran was to be divided into three “spheres of influence”—British (the southeast), Russian (the north) and neutral (the rest of the country, much of it desert). Iran was not invited to send representatives to the conference which led to this agreement, and naturally felt extremely affronted by its terms. Soon the ex-viceroy of India, Curzon (who was British foreign secretary from 1919-24), was pressing for Iran to be brought even more securely under British control. In the same period, agitation for democratic reform within Iran was at best ambiguously received by England, as one of the main demands of the reformers was the expulsion of foreign economic and political interests from the Iranian scene. The fall of the Qajar dynasty in the 1920s and the rise of Reza Shah (the king deposed by the Allies in World War II) were also seen by many Iranians to have been engineered by the British, and there is still scholarly disagreement as to whether the British were in fact involved in the coup that brought Reza Shah to power, and if so, how far they were implicated. Certainly they were instrumental in removing Reza Shah, and certainly, too, they strongly influenced the American decision to remove, by CIA covert action, the popularly elected prime minister, Mosaddeq, in the 1950s. Iranian suspicion of the power of the British to influence events in Iran, and of their motives and behind-the-scenes methods, has not therefore been—to put it mildly—without foundation. Given such a background, Dear Uncle Napoleon’s obsession with the British becomes more explicable. His (lying) claims to have been active in the Constitutional Movement for democratic reform, and to have fought against insurgents in the south of the country, locate his career in times and places where he could have come into conflict with what were seen as British interests and machinations. The British maintained connections to both sides of the constitutional conflict, and they at the least liaised with tribal factions antagonistic to the central government. Dear Uncle’s paranoia is an extreme and comic exaggeration of a common phenomenon in Iranian culture, a conviction that much of the last two centuries of Iranian history, if not every minute detail of it, has been engineered from outside, and probably from Britain and/or (since World War II) the United States. This conviction can lead to what seem, for a Western observer, to be incredibly bizarre claims, including the very commonly held belief among some Iranians that the British organized the Islamic Revolution of 1979, and the almost equally common claim that the United States deliberately provoked the Gulf War against Iraq in order to have an excuse to send war ships to the Persian Gulf so that they could keep a closer eye on Iran. To question these claims is to label oneself either as hopelessly naive or as a sympathizer, open or covert, with those who wish Iran ill. The brilliance and popularity of Iraj Pezeshkzad’s portrait of this desperately paranoid patriot has led to a Persian equivalent of the term “Dear Uncle Napoleon-itis” being adopted as a name for such readiness to see conspiracy theories and the hidden hand of the West behind any and every local Iranian event. And yet there has been a real irony in the popular reception of the novel. In the same way that surveys in the United States have found that some of the audience for the fictional television bigot Archie Bunker in fact identified with his lumpen racist and sexist tirades, rather than finding them ridiculous, many readers of My Uncle Napoleon have taken the novel not so much as a lampooning of such paranoia but as a confirmation of the lasting relevance of such attitudes as a way of interpreting Iranian political life. There is also of course an irony, of which I could not fail to be aware, in the fact that this novel, which bases so much of its comic effect on suspicion of, not to say hatred for, the English is here translated into English, and that the

Description: