My Transportation for Life [2.44 MB] - Veer Savarkar PDF

Preview My Transportation for Life [2.44 MB] - Veer Savarkar

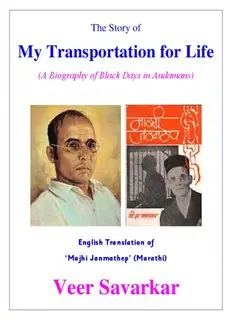

The Story of My Transportation for Life (A Biography of Black Days in Andamans) English Translation of ‘Majhi Janmathep’ (Marathi) Veer Savarkar PUBLISHER'S NOTE It is but natural that we should feel particular pleasure in publishing the Book, "The story of my transportation for life" which is the English version translated by Prof. V. N. Naik, M.A., Principal, Narayan Topiwalla College, Mulund, from the original Marathi Book " MAZI JANMATHEP" written by Mr. V. D. Savarkar during his internment at Ratnagiri soon after his release from the prison in Andamans and at other places in India, where he was detained for well neigh fourteen years. The pages depict the story of the sufferings and persecutions inflicted upon the author and other political prisoners and it was no surprise that the book should have been so popular among the Marathi reading public that its first edition which was published in the year 1927, was sold within a few months. A second edition also was in print, when all of a sudden, the then Government of Bombay thought it advisable to prescribe the book. It was only in the year 1947 that the ban thereon was removed by the popular Government and the second edition was published that very year. The translation in English we are presenting to our readers is a version from this second edition. Prof. Naik has not only rendered a correct and classical translation, bus has brought out the real spirit of the author in the pages of this book and has so faithfully rendered the account of the physical and mental torture and the harrowing tales of inhuman sufferings inflicted upon a person whose only fault was that he felt that India should not be ruled by a foreign Government. If at all, reform in that prison life has come, it was due to the social and educative work of Mr. Savarkar during his stay in that "Dark dungeon and house of despair". The poet describes our sweetest songs to be those that tell of the saddest thoughts and in that sense the book truly reads like a romance and confirms that truth is stronger than fiction. In a word it is a human document and no phantasy. We cannot but close this note unless we offer our thanks to Principal V. N. Naik for translating the Book into English for us which he has done so faithfully and ably. We also record our thanks to Prof. V. G. Mydeo, M.A. for the valuable help and assistance he gave us from time to time. We hope the Book we are presenting to the reading public will not only make it an interesting reading but will be appreciated by them as a historical record of the sufferings inuicted upon one of the sons of India. TRANSLATOR'S NOTE The book--The Story of my Transportation-is an English version of Mr. V. D. Savarkar's original work in Marathi entitled, qqqqÉÉÉÉÉÉÉÉffffÉÉÉÉÏÏÏÏ eeeeÉÉÉÉllllqqqqÉÉÉÉPPPPååååûûûûmmmmÉÉÉÉ It is the story of the great rebel's incarceration for ten years in the Cellular-Silver-Jail of the Andamans. Swatantrya Vir Savarkar was sentenced by the High Court of Bombay at the end of 1910 to fifty years' transportation to the Andamans is the result of his revolutionary activities in India and England. Actually he was released from that prison after a period of ten years, to finish up with his confinement in the jails at Ratnagiri and Yeravada. The story begins with with his prison life at Dongri and ends with his last day in the jail at Yeravada. The thrill and interest of the original narrative, interspersed as it is with musings and meditations on topics of the day, and on others of abiding interest for life, with all the insight and illumination that they bring along with them, I have tried to retain in the English translation with such omissions and additions as the author himself has suggested to form the basis of the translation. I have used for that purpose the method of free and fair rendering of the original. I have not translated the original word for word, though I have not departed materially from the text before me. I am glad to inform the reader that the author himself has gone through the translation, and the English work appears before him with the seal of the author's approval. I need not dwell here on the life and life-work of Mr. V. D. Savarkar, work that is well-known to all who know anything of the Hindu-Mahasabha and it’s functioning during the last ten years. His life from young manhood to old age has been one long sacrifice for the Ideal. And the story before the reader reveals the mood and temper, the yearning and strenuousness, the patience and courage behind that dedication. One may differ from Mr. Savarkar on many a point of detail and principle; but one cannot say, with this book before him that he has not suffered and <sacrificed, and last but not the least, he has not served the country by that sacrifice and suffering. As these page will reveal to the reader, he is no believer in more sentiment; he does not believe in rousing mass sentiment, like the mounting wave of a storm-tossed sea, only to help it tumble down in the sands, and roll back wasted to the sea from which it mounted so high. He has discussed in this his prison-diary, so to say, for it is not a diary at all, many questions of public interest that must come home to the business and bosom of men in India, and particularly to the business and bosom of patriots and leaders who have striven hard and are striving hard today for unity and freedom in India. India is free, but she is riot free as we should have liked it to be. We have still to toil and sweat in tears and blood to unite, consolidate and build up for the fruition of that grace of freedom. Savarkar is no narrow-minded Hindu Sanatanist. He does not swear by revolution, armed or otherwise, for the sake of revolution. He is a hard-headed Maharashtrian and thinker, and a far-sighted worker. He is a poet and man of letters, and an inspiring speaker. He came back to politics in the evening of his spent-up life, the spring and vitality of which had been all but sapped by the unmitigated hardships of his life as a whole, and, particularly, by what he had to pass through in the prison of the Andamans. If prison-life in India and especially for the Indian political prisoners, has at all improved, the credit of that improvement must go entirely to the work of uplift and awakening he carried on relentlessly during his ten years' stay in the 'Silver Jail' of that island settlement the pages of the book before the reader make that fact clear, as clear as day light. Savarkar came back to life when he was past fifty, and lie revived Hindu Mahasabha as its President for five years, as none before him had done it. He has given the Hindus and all Indians a message to live by. He has charged them to live as true patriots, and to so live that life that India may become, under God's providence, the glory and the greatness that she was in the noble past, as typified. for instance, in the reign of Asoka. "One country, one people and one goal; victory to the Mother"-that is what he has toiled for and suffered for. And that urge within him, this book makes it clear to us in burning pages, as no other prison-diary written by an Indian for an Indian has made it before him. Time is not yet to judge whether his name "is writ in water" or shall abide. Savarkar himself will leave that for his Maker to decide. His is to work and leave the fruit of it in the hands of Him who has made the world and looks after it. V. N. NAIK INTRODUCTORY Thousands of my countrymen in Maharashtra and the rest of India have sympathetically expressed their desire to hear the story of my life in the Andamans and of the hardships that I had to pass through during my imprisonment in that island. Since my release I have also felt that the yearning to narrate the story, and share in the tears that my dear ones will shed while reading these pages. Sorrows remembered are sweet and that sweetness I hope will be mine, while I unfold page by page that heart-rending tale. All the same, the events of that story, even when they had been upon my lips, had not found expression in words up to this time. Like some thorny creeper growing in darkness, they seemed to wither away at the touch of light. They were dazzled and blinded by the anticipated glare of publicity. Occasionally the thought came to me that I did not suffer what I had suffered to tell it to others! Then it would be all a stage-play. Sometime there was the irrepressible longing to recount the tale of my bitter experience because those who had died in the midst of them had not communicated them to the surviving members of their families. They had not that consolation and I should do it for them. Those sufferers are not with me today-my fellow-workers and prisoners. Why should I, then, in their absence from this world, reveal their sufferings and enjoy the relief and consolation denied to them by Providence? The sweetness of sorrow remembered was not theirs. Why then should I claim it for myself? Will it not be an act of betrayal towards them as also of self- deception? And have not several persons suffered like me before this? Have they not gone through similar dangers and catastrophies, and are not many more yet to face mountains of trouble like me? Why should I then make so much noise? What is my tom-toming before the sound of their kettle-drums? In the bivonac of life and in the noise of the battle-drum, let me not sound my tom-tom. Let me be silent. But grief is always eager to express itself in words. The cry of grief is irrepressible. Nature has bound that drum round its neck and it must beat it. A falcon pounces upon its prey and carries it in its claw. The little prey sure not to escape from that claw, still sends forth its yell, knowing full well that no help will come to it in that dire plight. It is Nature’s impulse that makes it utter that piercing sound. From the wail of that bird to the funeral march accompanying the corpse of Napoleon brought back from St. Helena to find its grave in Paris, with flags at half-mast, with drums beating and trumpets sounding before the coffin is let down in its last resting place, is not all this wail of sorrow but an expression and outlet for suppressed grief? Every being in this world finds an outlet for the soul pent up with grief, “in words that half reveal and conceal the soul within.” It is the second nature of grief to cry out. Why then should I not add the sigh of my individual sufferings to the countless sobbings, passing into the infinity of sky, from the souls of innumerable sufferers, and seek the relief that such heaving may bring me? Surely enough the vast deep has space enough in it to contain that sigh. My individual self would often be ready, with these musings, to give out what I had held so far within my bosom. But circumstance had held me back and would drag me back. For, in my present position I cannot give to the world just what is worth knowing in my life in the Andamans. What can I expose is but the surface, relatively insignificant, and superficial. And I have no zest in me to put it in words. What I would tell I cannot, and what I can tell has no sufficient spur to goad me on. I had almost decided to say nothing lest I may present the picture in blurred outline and without proper perspective. To give a colourless and tame account of that story was to render it worthless. I had better wait for the day when I could narrate it in full, omitting nothing and exaggerating nothing, and giving full vent to my thoughts and feelings about it. If the day were not to arrive, let it to go to the grave where it will be buried along with my body. Let not the world know it, it does not lose its worth thereby as its edge is in no way blunted by oblivion. In the vast well of loneliness and sound that this world is may remain deposited in tears, and that will not stop the world from running its appointed course. Such were the thoughts and counter-thoughts that kept an assailing my mind. In this woe-begone condition of my mind, I had to put off my task of writing the story of my prison-experiences for the information of my fellow-countrymen. Many that entered the Andamans later than I, and many who went out of it earlier, had published such writing and narrated their reminiscences. And I have read most of them. Those who were in prison elsewhere for a period of not more than six months, have given to the world an account of their life in prison. And I have seen them as they were being published. But such kind of autobiography has always incurred the charge of self- adulation, and I did not desire to be tarred with the same brush. So the mind has hesitated all along, and the hand has been restrained by the thought. To be communicative, to open one’s heart to persons dear and near to us, to state everything freely and frankly is the natural tendency of the human mind. It revels also in the expression of triumph over difficulties and dangers, it exults in enlarging upon those conquests over trials dead and gone. It finds a sort of joy in dwelling long over them. But circumstances intervened to postpone that desire and reap the joy of its fulfillment. But my friends insisted that I should give them some account of my life in the Andamans, however imperfect, brief and partial it may be. Even that much would be interesting to them, the friends added. From the youngest lad going to school right up to the oldest among my friends the demand became persistent and imperative. The publishers pursued me with it as much as the school boy. And it emanated from a sincere and loving heart. So much so that I could no longer put it off. Not to accede to it would be an excess of modesty and pride combined. It would mean disappointment of public expectation. Hence I finally resolved to write these pages and to give to the world such account as I could render of my experience in the Andamans, I could not narrate the whole story at the time for reasons that were obvious. Such a cogent, clear and well arranged narrative must bide its time. The reader must be content with what I can present to him and with the way in which I shall present it. Whatever is imperfect, one-sided, or inconsistent in the story, must be accepted with pardon, for it is production of time and circumstance beyond my control. The reader must wait before he can have from me a perfect piece of writing. I am fully aware of the value of such writing for the public at large. But in these reminiscences, I am not confining myself to the narration of events and incidents merely. For I regard the reaction of these events more important than the events themselves. So I have woven in this bare and imperfect record of events, my thoughts and feelings at the particular time, which I have considered more interesting and enlightening. But the recollections themselves are but piece-meal jottings, and the feeling and thoughts evoked by them faint, imperfect and suggestive. I could not help otherwise, and, therefore I would beseech the reader not to draw any final conclusions from the bare record I give him. Though I have not been able to give the story in all its aspects and with a fuller detail, I must ask the reader to believe me when I state that whatever I have written I have written with particular care to present the whole truth and nothing but the truth. The thoughts, feelings and happenings recorded in this work are but expressions of my reaction at a particular phase and time of my life in the prison of the Andamans. It is a historical document and should not be confused as being anything more than pure history. I expect the reader to peruse it in the spirit I have written it. V. D. SAVARKAR. CHAPTER 1 The Goal at Dongri, Bombay “ You are sentenced to fifty years transportation. The International Tribunal at Hague has given judgment that England cannot be constrained to hand you over to France”, said Mr. X to me. “ Well then, I had never depended on any hopes from that quarter. But can I have a copy of judgment to look at?” “That does not rest with me, though I will try my very best for you. Yet the fortitude you have shown in hearing the news that has wrung the heart of a stranger like me, does not make me think that you will wait for any help from an outsider like me,” said my interlocutor almost overwhelmed with feeling. “ Do you really believe that this news or any other news like this does not terrify me? But as I am determined to face this danger and have courted it deliberately, I have now grown impervious to it. Had you have been in the same plight, you would have proved as resolute as myself. For every one can crush such experiences on the threshold of his strong mind. All the same, I am grateful to you, indeed, for your help and sympathy.” Just then I heard some one coming. The gentleman instantly left my room and went his way in the opposite direction. I withdrew a few steps in my cell and kept standing. The word ‘fifty’ kept on ringing in my ears. In a moment those, whose footsteps I had heard coming near my cell, appeared on the scene. The Officer opened the door and his attendant served me my meal. Till the decision of the Hague Tribunal, I was not treated as a prisoner either in food or clothing. Today I had my usual meal. Perhaps the goaler had not yet received the order of the Court. I finished my food but did not that day touch the nice things in it. The Officer questioned me about it- “ Why, why, Sir, have you not touched these things? Why don’t you dine as usual?” “ Of course I had my fill. But I have taken such things as are common to all prisoners here. For, who knows, I may be put tomorrow to do the work that they do now. Then I may not get the food that I have now. The dirty food of a regular prisoner is to be my lot henceforward. Why not, then, make friends with it from now? It will last me for life.” I replied with a smile. To it the Officer impatiently retorted, “ No, no, that shall not be. The order has already been received, I hear to send you back to France. You, to serve your sentence as a prisoner! Never, never. God will not grant it.” At that instant a watchman came up running, and said that the Jamadar was following. The door was slammed. The warder and his attendant proceeded further. Soon after came the Superintendent and informed me, albeit courteously that thenceforward I was to wear the prisoner’s uniform and would be given the food he ate. He conveyed the news that my life-sentence of fifty years commenced from that day. I got up, took off the clothes I had worn so far, and began putting on those that I was to wear as a prisoner. A thrill of horror vibrated through my whole being. These clothes, I felt, I was to use all my life. No longer I was to part from them. Perhaps in these very clothes my dead body may be taken out from the prison door. Faint, shadowy thoughts these-but the mind was overcast by them. The Superintendent kept on walking on sundry things and I tries to divert my mind by engaging myself in that conversation. As if not to give me the solace I was seeking for, a sepoy brought to the Superintendent what looked like an iron plate. It was the badge, with the number marked on it, which a prisoner has to wear on his breast. The badge shows the date of his release. What was my date? Am I ever to be free, or death alone was to be the date of my release? I cast my look on the badge and its number with mingled feelings on longing and despair, humour and curiosity. The year of my discharge was 1960. for a moment I did not take in the full significance of that writing. But, in a minute or two, it flashed upon my mind. I was sentenced in 1941 and I shall have my discharge in 1960! The British Officer grimly observed, “No fear about it, the benign government was to release you in the year 1960!” To him I replied in the same vein, “But Death is kinder. What if it lets me off much earlier?” Both of us laughed. He laughed spontaneously while mine was a forced laugh. After discussing a few matters with me, he left the place. I sat down; we two alone were in that cell confronting each other; myself and my punishment. In that gloomy room we were staring each other in the face. The rest of the day’s story and the turmoil within, I have depicted in my poem, ‘The Saptarshi.’ Its first part contains it and I need not dwell upon it here. The Second Day “It is just day”, so the Jamadar greeted me, “ although your sentence started from yesterday, the Saheb has asked me to take out for your morning walk as usual, and so I am here.” I went down with him to have my constitutional. During my absence my cell was searched through and through. My kit and my books were removed from that place. I was having my perambulations in the open square downstairs. My former clothes were not on my person. I was dressed in the garb of a prisoner. And curious eyes were looking on me to see how I appeared in my new vestments. From the hospital, along the passage, and through the windows, they observed me finding out one excuse or another to do so. Some to satisfy their idle curiosity and others full if compassion for me! The goal of Dongri is in the very heart of the town. For I could see high up and around me, chawls and other tenements on all sides of it. Everyday when I was brought down for exercise, I had noticed people from these neighbouring houses standing in the windows and the galleries to have a look at me. Men and women were there peeping and whispering. They stayed there till I had done my morning walk. Sometime, evading the watchman, I used to look up, and exchange salutations with them. I was pleased in my heart by the regard they had shown to me. I felt then that we, who had worked for their liberty, were rotting in jails, while they were silently looking on without the least notion of taking revenge. Once I learnt that the guard had administered a stern rebuke to the landlord of one of these chawls. So I decided to walk in the square and never once look up so that none of them should suffer on my account. During my walk I used to recite the whole of the Yoga Sutras, and recalling each text to my mind used to meditate on it. Today, while I was thus absorbed, the guard pulled me up saying that the time was up and I must return to my cell. I climbed up the stairs and went to my room. Being lost in thought I sat in one part of the room for a long time to come. Suddenly, I heard the knocking on the door and looking up saw an Havildar coming in. he had a prisoner with him who carried a bundle on his head. The reverie had made me oblivious of my surroundings; so I kept on looking at him with vacant eyes, whereupon the Havildar said to me, “Sir, do not please be anxious. God will make the days easy for you. He is a witness to the dire distress, and he will be your stay in it. I and mine, I assure you, were full of tears