much ado about nothing PDF

Preview much ado about nothing

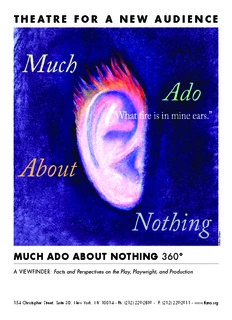

T H E A T R E F O R A N E W A U D I E N C E er as Gl n o Milt MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING 360° A VIEWFINDER: Facts and Perspectives on the Play, Playwright, and Production 154 Christopher Street, Suite 3D, New York, NY 10014 • Ph: (212) 229-2819 • F: (212) 229-2911 • www.tfana.org TABLE OF CONTENTS The Play 3 Synopsis and Characters 4 Sources 8 The Comedy and Society of Wit 14 Perspectives 16 Selected Performance History The Playwright 19 Biography 20 Timeline of the Life of the Playwright The Production 23 From the Director 25 Costume Design 28 Cast and Creative Team Further Exploration 32 Glossary 34 Bibliography About Theatre for a New Audience 36 Mission and Programs 37 Major Institutional Supporters Theatre for a New Audience’s production of Much Ado About Nothing is sponsored by Theatre for a New Audience’s production is part of Shakespeare for a New Generation, a national initiative sponsored by the National erer Endowment for the Arts in GlasGlas cooperation with Arts Midwest. on on MiltMilt Notes This Viewfinder will be periodically updated with additional information. Last updated February 2013. Credits Compiled and written by: Carie Donnelson, with contributions from Jonathan Kalb | Edited by: Carie Donnelson and Katie Miller | Additional research by: Jacqueline Tralies and Kathleen Hefferon | Literary Advisor: Jonathan Kalb | Designed by: Milton Glaser, Inc. | Copyright 2012 by Theatre for a New Audience. All rights reserved. With the exception of classroom use by teachers and individual personal use, no part of this study guide may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Some materials published herein are written especially for our guide. Others are reprinted by permission of their publishers. 2 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE: 360° SERIES TH E P LAY : SY NOP SI S AND CH AR ACTER S Characters Fresh from a military victory, Don Pedro, Prince of Aragon, arrives with his army in the town of Messina, where his friend Leonato is governor. LEONATO, governor of Messina A “merry war” of wits has long raged there between Beatrice, Leonato’s BALTHASAR, a follower of Don Pedro niece and ward, and Benedick, one of Don Pedro’s officers. Claudio, BEATRICE, niece of Leonato, an orphan another officer who is Benedick’s best friend, falls instantly in love with HERO, daughter of Leonato Leonato’s daughter Hero upon seeing her, and Don Pedro offers to help DON PEDRO, Prince of Aragon win her hand. It briefly seems to Claudio as if the Prince is wooing for BENEDICK, a soldier from Padua himself, but that worry is soon assuaged, Leonato and Hero agree to the DON JOHN, Don Pedro’s bastard brother match with Claudio, and a wedding is scheduled for the following week. CLAUDIO, a soldier from Florence To fill the intervening time, Don Pedro proposes a plan to trick Beatrice and Benedick into marriage by gulling each into believing that the other is in ANTONIO, Leonato’s brother love with him/her. CONRADE, a follower of Don John BORACHIO, a follower of Don John Don John the bastard, Don Pedro’s disgruntled brother, is determined to MARGARET, gentlewoman attending on Hero vex the Prince and everyone in the merrily legitimate aristocratic circle that URSULA, gentlewoman attending on Hero excludes him. He sees an opportunity in Claudio’s youthful jealousy. Don DOGBERRY, a constable John tells Don Pedro and Claudio that Hero is wanton and says he can prove it if they meet him outside her window that night. There they witness VERGES, a headborough Borachio, Don John’s sycophantic follower, addressing Hero’s maidservant THE WATCH Margaret as Hero, and conclude that Hero has been unfaithful. Shortly FATHER FRANCIS* thereafter, Borachio and his friend Conrade are overheard describing A SEXTON this plot and arrested by the oafish town watchmen, but the blundering MUSICIAN constable Dogberry is unable to bring the crime quickly to light. At the altar the following day, Claudio cruelly denounces Hero as a whore and she *changed from Friar to Father Francis for the production falls unconscious. Her distraught father at first believes the accusation and wishes her dead, but Friar Francis has doubts. He suggests a scheme to seclude Hero while publicly announcing that she has died, in the hope that the truth will reveal itself. Beatrice and Benedick, united in believing Hero wronged, confess their love for one another, and Beatrice demands that he kill Claudio to prove his love. Benedick, after hesitating, challenges Claudio to duel, but they are never forced to fight because the crime is revealed. News arrives that Don John has fled Messina, and Borachio confesses all. Claudio, believing Hero to be dead, is guilt-stricken and begs forgiveness from Leonato, who offers it on several conditions: Claudio must write an epitaph to Hero, hang it in her tomb, and agree to marry Leonato’s heretofore unseen niece, described as “almost the copy” of Hero. All this is done, and Hero is revealed as the mysterious “niece” at the wedding, where Beatrice and Benedick move toward marriage too. Don John is captured and brought back to Messina under guard, but Benedick calls for his punishment to be put off “till tomorrow,” after the dancing. MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING 3 TH E P LAY : SOU R CES Under the deceptively cavalier title, Much Ado About Nothing, Shakespeare conceived of comedy that totters on the edge of tragedy, where brothers-at-arms seek to murder one another and an innocent bride must “die defiled”1 in order to live with an unsullied name. Written around 1598, Shakespeare twists two found plots involving Hero and Claudio and Beatrice and Benedick together via the machinations of Don John and Don Pedro, respectively, and resolves them through the discoveries of Dogberry and his Watch. As director Arin Arbus states, “The myriad plots and the fact that nobody is speaking directly, lead to 0 0 confusion, misunderstanding and injury.” The sources of both the main 16 g, plot involving Hero and Claudio and the secondary romantic plot of hin ot N Beatrice and Benedick may have been drawn from the Italian literature ut o that had made its way to England as the last waves of the Italian Ab o d Renaissance entered early modern English culture. But Shakespeare not A h only draws the dual plots from Italian literature; he also drew the setting Muc o, of Messina, a city on the northwestern coast of Sicily, and, as many art u q scholars have noted, the philosophy on which the world of the play is First based. Furthermore, it is believed that Shakespeare sketched Don Pedro and Don John from real-life historical figures and the events that connect ttlAatAihhht lreeeevtihrm oaamHosr tutietauoeogrrjt’o oeyshth/ r Oao seCstnf oo rlcdcaluraiui tureypnlcdts doueo ioorlosfie t fioMFs pca,fuls oe rm tdhoisto seoeffs irc sntoophtea m,lesia .vcw yewMhs rdeoroiotv eltrlaeerovlderrnevsa aet iilhnanr l I a g atawa1nr nle5p hidjaeiru1c on sa6thft h o s ,“asS oualmtahun nSaunrddchcdk e khaeeMsn skr,apeoe aiddewsnttopa eclbe erloaueeda db lBgrolieioaenvv unee gdotddd efLne. roe otilhvldxtoeheoi’s idsvnt igLicna,o ” urioso by Ludovico Ariosto, translated by he Shakespeare Birthplace Trust - Library, FrAWPadeurdedidrmchaoieaoip almesdat oe penPMd adtcib oru oaeAtcnennfhr. otdi ad or AAieeesn dtxnsloMeop ’si s aunNti ocsntse rohtdsioreu eeeArvstsdy edti o inilnbolsfe gy Mdti. hs eSdO eebciis rferesfs leJepialonirtetnteaihiovdnnn’ensogc d ,He w F ij anteubao rarerw iihmnlotowhags,ui ovtecosree heynw nl ,b at aihmeSnxesee hi 1sntdasrt5t aa,kow 9kenbreryss1uipln ta,ttt e eactlieeandkods.reeu2se sn r i’O ttntsplhiy ttraolyM,al a nwcaEu nennacod.dgh r ol l di s h, “Ariodante and Dalinda” in Orlando FSir John Harrington, third ed., 1634; TStratford-upon-Avon, UK of Messina, Ariosto’s is set in Scotland, with cold, valiant knights and imprisoned ladies. Ariosto’s is a much more medieval setting and story than is Shakespeare’s second possible source, Bandello’s La Prima Parte de le Nouvelle. Bandello’s work, which may have come to Shakespeare through mid- sixteenth century English adaptation, is closer to Shakespeare’s; it supplies the setting of Messina, the character and name of Leonato, the name of Don Pedro of Aragon (King Piero of Aragon in Bandello), 1 5.4.63; all Act, scene and line numbers from Much Ado About Nothing in The Riverside Shakespeare. Ed. G. Blakemore Evans. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1974. Pgs. 332-362. 2 Humphreys, A R., ed. “Sources” in Much Ado About Nothing. Gen. eds. Richard Proudfoot, Ann Thompson, and David Scott Kastan. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 1981. Pgs. 5-25. 4 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE: 360° SERIES TH E P LAY : SOU R CES and more material for the Hero/Claudio plot.1 Further, scholar Claire de es McEachern states, nn a h o The social universe of Bandello’s novella is certainly more by J akin to Shakespeare’s Messina. Rather than court intrigue nsulis or the accidental landscapes of romance, he chooses to set bus i Trahcei emr,hspwa”mirj3hsoo a iaxsrcl tlinhod mtd riotfiyh ftwSye eii rnn rien n, Gn to hpwcteialerah obsgci,nlceo edhhss o o asrbiw rupOeemeys lm tvoe cesruuouirrco,nis ht f aeVi[ ndrsnaeie oclt seot]t eh n oadaczfrr, tie e aa“m a nbBloteoaoinis—rnstgnludy trte haehblendleyo d D ’hse setooa rnvanuces snheJreso s homiohootfnihn tlt dse ecoir dshi.cn 2a,im arianaul cchte r— Maltae et Gozae, cum circumjacention the northwestern coast of Sicily ssdBtoeeaunvinreecsldeo hispc i kspw .rHohevaritdo me’s a Shnhoyan ksoecrhs iponel aoarrrsde b ewre lititoeh v daei sftcaoom buierlia ahgrie ss traoe raryilv uiannlt defoererr shwt,e hrBi eclohav tehri.ec eTch aaenns de Siciliae et insulae Messina is located Regni 690; Tmhaey s htoarvye o tfh Beiera rtorioctes ainn dw hBaetn Heduimckp’hs rreoyms acnaclles ,“ otwr oa tt rlaeadsitti othnesi…r rtehpea rtee, Detail, Ram, 1 scorner of love…and of the witty courtiers in many Renaissance stories exchanging debate or badinage.”4 He links both traditions to Baldasar u d Castiglione’s pamphlet on courtesy, Il Cortegiano (The Book of the e é us Courtier), published in 1528 and translated into English in 1561.5 M © Castiglione describes an urban city “the spirit of [which] is one of 8; 2 5 1 intelligent happiness,” where its inhabitants “dance, cultivate music, o, c. and enjoy ‘wytty sports and pastimes.’ Accomplishments are achieved bin Ur ‘rather as nature and trueth leade them, then study and arte.’”6 This a d o calls to mind Dogberry’s remark, “to be a well-favoured man is the gift nzi a S of fortune, but to write and read comes by nature.”7 Scholar Stephen o ell a Greenblatt writes, aff R by The courtier, as [Castiglione’s characters] envision him, must one nce basuebb leetl qetotuie aasll syos ifas dtd tiehppelot Pmartai nmccyae kaainnndgd twoto a sdrin aagnn cidne mae laepkglienaagns tallyon,v t,eto .u ngHareaf fsmepcu ttsehtd eb e Baldasar CastigliLouvre, Paris, Fra voice, to engage in philosophical speculation and to tell amusing after-dinner stories. In order perform all of this without seeming “stilted and artificial… he must practice what Castiglione calls sprezzatura, a cultivated nonchalance…a technique for the manipulation of appearance.”8 Castiglione also illustrates a woman who comes to love a man “she had not shown the slightest interest in” simply because it was said by 1 Humphreys 6-7 2 “Introduction” in Much Ado About Nothing. Gen. eds. Richard Proudfoot, Ann Thompson and David Scott Kastan. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2006. Pgs 11-12. 3 Humphreys 8 4 14 5 Greenblatt, Stephen. “Introduction: Much Ado About Nothing” in The Norton Shakespeare, gen. eds. Stephen Greenblatt, Walter Cohen, Jean E. Howard. New York: Norton, 1997. Pg. 1382. 6 Humphreys 17 7 3.3.14-16 8 1382 MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING 5 TH E P LAY : SOU R CES others that they “loved together,” meaning they loved each other but did not know it.1 He also writes of a society in which “dark forces lie just outside the charmed circle of delighted lords and ladies.”2 Shakespeare’s play contains these sorts of “dark forces,” making Beatrice and Benedick into much more than the pleasant witty couple modeled in Castiglione’s work; Beatrice pushes the comedy to the edge of tragedy with her “Kill Claudio;” and Benedick, instead of choosing his male companions over a woman as good courtiers should, challenges his friend Claudio, with the full intention of killing him. n ai p Shakespeare’s understanding of the history of Messina may have d, S also influenced his setting and the relationship of two of its major adri M characters, Don Pedro and Don John. Situated on the northwest coast al, av N of Sicily, Messina was a major port that lay between Italy and North o e Africa, and Italy and Spain. Scholars such as Richard Paul Roe and Mus 1; Murray J. Levith have maintained that the English would have specific 7 5 1 associations connected to the city. Levith writes that the English would a. o, c have seen Messina as “the launching point for the last galleys war in ell o C naval history,”3 known today as the Battle of Lepanto, which was fought z e h in 1571. The battle was so famous that most of Europe commemorated ánc S the victory with a holiday. A special celebration was held in Messina nso o to honor the Captain General of the victorious fleet, Don John of by Al Austria—the illegitimate son of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and ustria half-brother of Phillip II of Spain. The uneasy peace between Don John of A n and Don Pedro at the beginning of the play could have been inspired by ua n J an uneasy alliance between the brothers after the Battle of Lepanto. In Do England, Elizabeth I was said to have shown romantic interest in John, but he had other notions. Don John of Austria was a staunch Catholic and his interest in England lay with Mary Queen of Scots, a prisoner held at the pleasure of her Imperial cousin. John schemed to rescue Mary, marry her and proclaim her England’s rightful Catholic queen with himself as England’s king. The plot was abandoned when Phillip II refused to condone his half-brother’s play. In fact, Phillip consistently thwarted his brother’s attempts to gain power. Although Shakespeare’s Don John is only named a bastard once in the play, Roe writes, “Elizabethans…attending a performance, would have sensed early on who this John the Bastard…is meant to be.”4 Whether or not the real Don John—who was handsome and quite popular in Catholic Europe— was a “flattering honest man” or a “plain-dealing villain”5 is not known. It is quite clear, however, that Shakespeare had no difficulty borrowing from the circumstances of his life; neither did he have qualms about capitalizing on Don John’s illustrious reputation. 1 Humphreys 15 2 Greenblatt 1382 3 “Beyond the Signory: Much Ado About Nothing” in Shakespeare’s Italian Settings and Plays. New York, US: 1989. Pg. 80.; Galleys were types of ships used in warfare that were propelled by rowers. 4 “Much Ado About Nothing: ‘Misfortune in Messina’” in The Shakespeare Guide to Italy. New York: Harper Perennial 2011. Pg. 232. 5 1.3.31-32 6 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE: 360° SERIES TH E P LAY : SOU R CES It is within the context of these cultural, political and literary sources of Much Ado About Nothing that one can view the events of the play not as a good deal of fuss over insignificant occurrences, but as scholar A.R. Humphreys writes, “… elements loosely similar but so markedly variant in tone and incidents that only the shrewdest of judgments could co-ordinate them into a theme of such tragicomic force.”1 Perhaps it is this that makes Much Ado About Nothing as fresh and alive today as it was over four-hundred years ago. Considering that Much Ado is, after all, about the fragility of the human heart, and the games humans play to protect it, it is easy to understand why the play itself has become a major source for uncountable works of art. 1 13 ar, m Wei ek, h ot bli Bi a ali m A a n n A n gi o z er H 3; 9 5 1 g, er b n e g o H ns a d Fr n a n u a Br g or e G by m u ar bis Terr Or es at Civit n Messina” iermany “G MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING 7 TH E P LAY : TH E COM ED Y AND SOCI ETY OF W I T Of all of Shakespeare’s plays and characters, few of them can be said to have spawned a genre of comedy—save Beatrice and Benedick in Much 9 Ado About Nothing. From Restoration comedies to Hepburn and Tracy 94 1 movies, these characters have inspired generations of writers to create Rib, their own witty couples who resist their own coupling and use language m’s a d A as an armor and a weapon in order to protect what director Arin Arbus or calls their ‘fragile hearts.’ But it is more than just their fully realized oto f h p personas or their fragile hearts that have sparked imaginations—it is their al n o use of language, their wit, that has engendered such emulation. It is clear oti m o that Shakespeare understood the delights and dangers of language; one pr n, need only hear the gulled Benedick ruminate on Beatrice’s language bur p e with “Ha! ’Against my will I am sent to bid you come in to dinner’— e H n there’s a double meaning in that”1 or ponder over “Kill Claudio”2 to hari at K immediately see examples of both. But where did Shakespeare learn this d n a language? And why were these characters such “meet food to feed it as acy Signior Benedick” and “my dear Lady Disdain”?3 Perhaps some basic er Tr nc answers lie in the early modern obsession with language and, in turn, pe S in how Shakespeare used his predecessors’ theories on the comedy and language of wit. Defining ‘wit’ now, just as in early modern England, is no easy task. It takes up no less than four and a half pages of the first edition of Oxford English Dictionary. At its most fundamental definition, the word wit is a noun that is “the seat of consciousness or thought, the mind.” But it is also “the faculty of thinking and reasoning,” as well as “the faculty of perceiving” as in, the use of one’s five wits or senses.4 Furthermore, wit also represents the quality of the mind, and the ability of the user to express himself quickly and aptly, usually “calculated in order to surprise or delight by its unexpectedness.”5 Wit, therefore, will be defined as the faculty and quality with which a person uses calculated language in order to surprise or delight, even deceive, the listener. It is a definition that the so-called University Wits—a group of university-educated playwrights active in the 1580’s and early 90’s that included Christopher Marlowe, Robert Greene and John Lyly—might have approved. In Shakespeare’s England, the faculty and quality of a person’s wit depended greatly on their status within the society and the education that accompanied their status. Still, a man could rise above his station on his wits. This can be seen with Shakespeare’s steady rise from an anonymous, provincial upstart to a wealthy shareholder in James I’s patented company of players—a playwright whose name was so valued that his name was placed in a prominent position on his printed plays. His name then, as now, had become a commodity, and his use of 1 2.3.257-259; all Act, scene and line numbers from Much Ado About Nothing in The Riverside Shakespeare. Ed. G. Blakemore Evans. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1974. Pgs. 332-362. 2 4.1.289 3 1.1.121, 118 4 II.1a, 2a, 3a, 3b 5 II.7a, 8a 8 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE: 360° SERIES TH E P LAY : TH E COM ED Y AND SOCI ETY OF W I T language was legendary, possibly infamous as Ben Jonson recalled in n, o d his posthumously published notebook of 1640, Timber, or, Discoveries; on Made upon Men and Matter ery, L all G He was, indeed, honest, and of an open and free nature; had ait an excellent fancy, brave notions, and gentle expressions, Portr al wherein he flowed with that facility that sometime it was on ati N necessary he should be stopped...His wit was in his own © power; would the rule of it had been so too.1 17; 6 1 “His wit was in his power,” Jonson wrote, but it can also be said that h, c erc his wit was his power. It is perhaps telling of the value of language b n e and wit within a society—especially one as stratified as England—that Bly n a a young man could rise in both fortune and station based primarily on m v a h his wits. Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries and break with the a br A Catholic Church may have confused the country’s spiritual life; but with by n Protestantism, which lacked an intermediary between the people and nso o God and thus required an individual familiarity with religious texts, n J mi a came an interest in literacy and education. As England’s prominence BenjUK and wealth grew during Elizabeth’s reign, the humanist Renaissance of Europe’s great kingdoms spread to England, primarily in the form of Greek and Latin literature. A new sense of English-ness was developing, along with an interest in exploring the limits of the English language. By the time Shakespeare entered London, conditions, both among the commoners and aristocracy, were ripe for a writer who could appeal to both. If Christopher Marlowe set the stage with his “mighty line,” Shakespeare and his company were able to borrow from the newly explored literature that, by then, was known even by the groundlings, while inventing new English words and phrases that also appealed to the lords and ladies in the box seats. As Shakespeare illustrated in Twelfth Night’s Sir Andrew Aguecheek and his notebook of found words, Londoners—and fashionable society in particular—were preoccupied with expanding their vocabulary, and showing it off. Just because a writer or speaker could invent new words, however, did not mean they could use their wits, as evidenced by Sir Andrew. Here, they found theories of language in Greek and Latin Literature, and they illuminated and expanded upon the theories, making them distinctly English—if not in theory than in practice. The English found many of these theories in the second book of De Oratore, written by Cicero, the Roman senator famous for his oratory skills, in 55 BCE. In the sixteenth-century, school children were taught from De Oratore, as evidenced by Roger Ascham posthumously published work The Schoolmaster (1570). Ascham was a prominent scholar and tutor to young Princess Elizabeth Tudor.2 He writes, There is a way, touched in the fine book of Cicero, De 1 “Documents: Ben Jonson on Shakespeare (1623-37)” in The Norton Shakespeare, gen. eds. Stephen Greenblatt, Walter Cohen, Jean E. Howard. New York: Norton, 1997. Pgs. 3360-61. 2 McDonald, Russ. The Bedford Companion to Shakespeare: An Introduction with Documents, 2nd edition. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2001. Pg. 64. MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING 9 TH E P LAY : TH E COM ED Y AND SOCI ETY OF W I T Oratore, which, wisely brought into schools, truly taught… would also, with ease and pleasure…work a true choice and placing of words, a right ordering of sentences, an easy understanding of the tongue, a readiness to speak, a faculty K U to write, a true judgment, both of his own and other men’s n, o d doings.1 on m, L Composed in the form of a dialogue, Cicero describes comedy and eu us M laughter, among many other linguistic and rhetorical tropes that a good h speaker should employ. Further, he describes several types of wit, Britis 0; namely “’one employed upon facts, the other upon words.’ The former, 40 1 wit ‘upon facts’ is of two types: the anecdotal narrative [a true account e, c or at of a tale]…and the technique of impersonation.” Of primary concern to Or e early modern English writers and dramatists was “the latter, wit ‘upon e, D g words,’ which produces laughter through ‘something pointed in a phrase pa d or reflection.’”2 It is thought that Shakespeare would have read Cicero’s ate n mi work in Latin, absorbing its theories and making them his own. u Ill Another influential Italian work was The Book of the Courtier, written o, d bisy b Bealiledvaesda rto C baes ttihgeli obnaes iisn o1f 5B2e8a.t rTicrea nasnladt eBde ninetdoi cEkn’gs lwishit ians 1w5e6ll1 a, si t del Praa, the Movaf eltuhseseis n boaof’ osl eksa,o rscncieihntoygl ,a( srce iRevui l“istSsy o,M ugrcrcDaecose”nf auinlldn te hwsissr, i gtewusii,td ,“ eai)tn .p dDr oethmseco rditbeigisn ntghit eyth hoeuf cmmoaanntnei.sn”tt 3 Museo Nacional Don Juan d’Austri TocovaGpahofnnai eulveearut el’c ideBscdnd s ou…mtmtbW wieo.eoatol ohmatraaC ileaksthtdoire klsp esaivlyigyo,yeca n los ,t ouci fBh s tdoi boihooyeedtageeuhite r m h tatltsbdsaeir i onee odetim eenros grCrsniigtr dsvercswet: e o hace tenmlsow eaouedi’pten ssebru uolixi Pty nntgriltdfupeiher aac nhceinfacerniguvgh s tdon ebcoilecac ,s.ude cy rr o slor diBsl’ba tpowtust iriieauhs Cesrwt ijicertgetsteroiaiehanisedichscnrps—isuret t na te e feoesrosoa lrrooealawfhf,r ynu n ’ot onB ssiadnlt na hr uu et o a chgnefcvlpwndororeeh aiewis oomd sr ngridvmytlnnaaiosieauit sdtsctnesdcdarhri iekcugnirouitnroace,ircd elfs e ulo s ttt mwr iditos sffaocohaost e as euegn,thnos fe snsi iaaoisdlrnc ms ;o cnichhh itntomaht oiduaniheisoinnnn mtiaovetq qnyl ugeafysstou.su ahuek p a ritehTelee oph.—pmws hisd.efssH e4e eo a hiw iamgr fe nnona ur ii wge tfiwcst,ntihre e nhetgriae h,sdoiol t d yeeiilgfesvd s su i e,idin sugea l The Buffoon called ‘Juan de Austria’ by Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez, c1632; Madrid, Spain; The subject was a clown in the court of Phillip IV. His impersonations of illegitimate son of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor who died in 1578, were legendary in devising impossible slanders. None but libertines delight in him, and the commendation is not in his wit, but in his villainy; for he both pleases men and angers them, and then they laugh at him and beat him.5 1 in McDonald 65 2 Galbraith, David. “Theories of Comedy” in The Cambridge Companion to Shakespearean Comedy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. Pgs 7-8. 3 73 4 in McDonald 74 5 2.1.127 10 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE: 360° SERIES

Description: