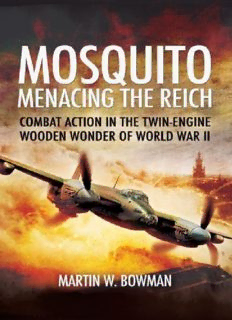

Mosquito: Menacing the Reich: Combat Action in the Twin-engine Wooden Wonder of World War II PDF

Preview Mosquito: Menacing the Reich: Combat Action in the Twin-engine Wooden Wonder of World War II

First published in Great Britain in 2008 by Pen & Sword Aviation An imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd 47 Church Street Barnsley South Yorkshire S70 2AS Copyright © Martin W. Bowman 2008 ISBN 978 1 84415 823 2 eISBN 978 1 84468 435 9 The right of Martin W. Bowman to be identified as the author of this work have been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Printed and bound in England by CPI UK Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper. For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED 47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk Contents List of Plates Chapter 1 Down Low Chapter 2 On High Chapter 3 Finders, Markers and Light Night-Strikers Chapter 4 Berlin or Bust Chapter 5 Fast Night-Striking Force Chapter 6 The Banff Strike Wing Chapter 7 Star and Bar Chapter 8 The Reich Intruders Chapter 9 The Shell-House Raid Chapter 10 ‘The Forgotten Front’ Notes CHAPTER THREE Finders, Markers and Light Night- Strikers O riginally formed from 3 Group, using volunteer crews, 8 Group had started as a specialist Pathfinder Force (PFF) on 15 August 1942 under the direction of Group Captain D.C.T. ‘Don’ Bennett and was headquartered at Wyton. On 13 January 1943 the PFF became 8 (PFF) Group and ‘Don’ Bennett was promoted Air Commodore (later Air Vice Marshal) to command it. The tough talking Australian ex-Imperial Airways and Atlantic Ferry pilot wanted Mosquitoes for PFF and target-marking duties. No.105 Squadron’s few B.IX bombers, which were modified B.IVs with Oboe radar, which no one wanted, helped him achieve his objective.91 Gee-H (from 1944, HS)-equipped B.IXs of 2 139 Squadron and Oboe II-equipped B.IXs of 105 Squadron spearheaded the Main Force bombing raids. Oboe had first been used on 20 December 1942. No. 139 Squadron went in with the target-marking Mosquitoes of 105 Squadron, sowing bundles of the thin metal strips called ‘Window’, which produced a ‘clutter’ of blips on German radar screens to give the impression of a large bomber force. They made diversionary attacks called Spoofs on other targets to attract enemy night fighters anything up to 50 miles away from the Main Force during the attack. Bennett’s Mosquitoes were to prove so successful that ultimately, eleven Mosquito-equipped squadrons operated in 8 (PFF) Group (the other eight squadrons being equipped with Lancasters). In addition, 1409 (Met) Flight was established at Oakington on 1 April 1943 using Mosquitoes and crews from 521 Squadron, Coastal Command at Bircham Newton. ‘Nuisance’ raiding had begun in April 1943 and was so successful that by the summer a Light Night-Striking Force (LNSF) of Mosquitoes was established. Mosquitoes went in up to an hour before the main attack, descended slowly and released their Spoof cargoes of two 500lb bombs, two target indicators (TIs) or ‘sky markers’ (parachute flares to mark a spot in the sky if it was cloudy)92 and bundles of Window. German fighter controllers sent up their night fighters, so that when the ‘heavies’ did arrive, the Nachtjagdgeschwaders were on the ground having to refuel. No.139 Squadron first tried Spoof raiding on the night of 18 November 1943 when flares and bombs were dropped on Frankfurt. Various plain colours with starbursts of the same or a different colour prevented the enemy from copying them. On 26 November three Mosquitoes of 139 Squadron, flying ahead of the Main Force, scattered Window on the approaches to Berlin and returned to drop bombs. After having converted to the Mosquito at 1655 MTU at Marham, Flight Lieutenant Jack Richard ‘Benny’ Goodman93 and his navigator, Flying Officer Arthur John Linzee ‘Bill’ Hickox (after ‘Wild Bill Hickok’ of American West fame) were posted in October 1943 to 139 Squadron at Wyton. Benny Goodman had completed a tour of thirty-seven operations and 1,300 hours on Wellingtons. Bill Hickox had also completed a first tour on Wimpys, although he had been shot down and had to walk back through the desert. Their first operational sortie in a Mosquito took place on 3 November 1943, the target being Cologne. Benny Goodman recalls: Marking was to be done by 105 and 109 Squadrons, using Oboe. Our bomb load was four 500lb HE bombs and the attack was to be an all- Mosquito affair. Out first operational takeoff in DK313 was only marginally longer than out takeoffs from Marham in Mosquitoes without bombs. The acceleration was rapid and in next to no time we were at the unstick speed of around 100 knots and climbing smoothly away. We climbed rapidly to 28,000ft, levelled out and settled down to an economical cruising speed of around 250 knots (true airspeed). As we neared Cologne the first of the Oboe-aimed target indicators began to cascade down ahead of us. Bill took his place at the bombing panel and began the time honoured verbal directions: ‘Left, left, Steady...’ and ultimately, ‘Bombs gone.’ We then turned for home, more bacon and eggs and bed. The post-flight interrogation was much the same as on any operational squadron in Bomber Command, with one important exception. 139’s full title was 139 (Jamaica) Squadron and we were all offered a tot of rum on return from every operational sortie the rum being provided by the good people of Jamaica. When I was on 139 we had with us a Jamaican named Ulric Cross, a flight lieutenant navigator, highly efficient and well liked. Later he became Lord Chief Justice of Jamaica. The best Oboe crews could place a bomb within a few yards of the aiming point from 28,000ft. However, since they had to fly straight and level for several minutes in the final run to the target they were vulnerable to flak and fighters. Moreover, they could only approach a given target from two directions; in the case of Ruhr targets, almost due north or south. The Germans quickly realized this and set up searchlight cones over the aiming point which they plastered with heavy flak. Another little trick was to position Ju 88s near the searchlight cones, at a higher level than the Mosquitoes. Thus, when coned, a Mosquito might first be blasted with heavy flak and then the barrage could suddenly cease. If the pilot wasn’t in a position to react instantly, the next happening would be a highly unpleasant squirt of cannon fire from the night-fighter. The average time for a trip to the Ruhr was 2½ hours, while a run to Berlin took about 4½ hours. To carry out such sorties in a Wellington had taken something like 5½ hours and 8 hours respectively. For this reason alone, Mosquitoes were greatly to he preferred to Wellingtons, it is better to be shot at for a short time than for a long time! At Wyton on 24 November 1943 ‘C’ Flight in 139 Squadron and its B.IVs were used as the nucleus to form 627 Squadron at Oakington near Cambridge. Benny Goodman and Bill Hickox were among the crews posted to the new squadron as Bill Hickox recalls: We went down to the flights after breakfast as usual. We were called in by the Flight Commander and told to go back and pack our bags, as we were to take an aircraft [DZ615] to Oakington, where we were posted to a new squadron being formed; 627. We duly arrived at Oakington, where we were told that we would be operating that same night. So without having time to unpack our bags, or go through the normal arrival procedures, we went to briefing, where we learned that we would be operating to Berlin along with two other crews. This was only my second trip to the ‘Big City’, but everything went well. Benny Goodman adds: It was a rule in Bomber Command that every new squadron became operational as soon as possible after it was formed and when we arrived, Bill and I found out that we were on the Battle Order for that night. The resident squadron at Oakington was No.7, a Lancaster squadron of the PFF force and on the day of 627’s arrival, the station was a hive of industry. A Bomber Command maximum effort was in preparation and Lancasters were being made ready for ops that night. To the Oakington effort would now be added six Mosquitoes of 627 Squadron. As the day wore on it became apparent from reports from the Station met office that operations that night had become questionable; a warm front was spreading in from the south-west more quickly that had been expected. At tea time the Lancasters were stood down, but 627 remained on standby and after tea we were briefed for an all-Mosquito attack on Berlin in company with 139 Squadron. Early that evening Bill and I boarded DZ615 and set off for the ‘Big City’, a trip which turned out to be completely uneventful except that on returning to the airfield we were flying in thick cloud and pouring rain. We broke cloud at 500ft, still in heavy rain and approached and landed very carefully. On reporting to the Operations Room for debriefing, we were astounded to be told that DZ615 had been the only RAF aircraft over Germany that night. Ops had been cancelled by Bomber Command at a very late stage but two of us were already airborne and were left to get on with it. The other pilot had trouble with his aircraft and turned back, which left me on my own. Bill Hickox has no doubts, as to what gave 627 its Esprit de corps It seems to me that 627 had it from the very start. Mind you, we had everything in our favour. We were flying the finest aeroplane in the world (Ah, de Havilland) and lived in comfort in the pre-war messes of a permanent station near the beautiful city of Cambridge. Cambridge provided good entertainment for nights off, ‘The Bun Shop’, ‘The Baron of Beef’ and even ‘Dorothy’s Tea Rooms’ being particularly memorable. Our CO, Roy Elliott, was the finest squadron commander I ever knew in a long RAF career.94 His Navigation Leader, William M. ‘Bill’ de Boos DFC, was a splendid Aussie character and even the Adjutant was a good type, as were all the other air and ground crews. We were a small, close knit community, proud of being members of PFF and of being part of the Light Night-Striking Force operating practically every night, even when the Main Force were stood down. We didn’t even mind being known as the ‘Model Aeroplane Club’. On the rare occasions on which we were stood down, it was great to pile into the Hillman flight vans and blunder through the blackout until we came to the bank of a river. There we would pull ourselves across on a chain ferry to a delightful pub called the ‘Pike and Eel’. How was it that it was always the Aussies who fell in on the return crossing? Benny Goodman continues. The winter of 1943-44 was famous, or infamous, depending on your point of view, because it saw the Bomber Command offensive against Berlin. Our C- in-C said that if we could lay waste the Big City the Germans would be brought to their knees.95 Sixteen major attacks were mounted but Berlin was not destroyed. The truth is that the target area was too vast and the weather, which could often be worse than enemy action, was appalling. Bill Hickox and I took part in seven of these attacks against the German capital and also busied ourselves with spoof raids against other targets, for example Kiel and Leipzig. We knew only too well that we were engaged in a battle of attrition, as was the US 8th Air Force and the outcome could be defeat for the bombers. During the Battle of Berlin we lost Squadron Leader ‘Dinger’ Bell, our Flight Commander. However, he and his navigator managed to bale out and became PoWs.96 At this time, Bill and I began to wonder if the sands were also running out for us when, on the way home from the Big City, the oil pressure on the starboard engine suddenly began to drop and the oil and coolant temperatures increased. Eventually the readings reached their permitted limits and I throttled back the engine and feathered the propeller. Now we were in the cart with a vengeance, for we had to lose height and were eventually flying along at a height and speed comparable to that of our heavy brothers, but with no means of defending ourselves if attacked. Moreover, since the only generator on the Mosquito was on the starboard engine we had to turn off our internal lights, the Gee box and our VHF set. So we drove on through the darkness with our fingers and toes slightly crossed and feeling very tense. Wouldn’t you? Eventually our ETA at the Dutch coast came and Bill switched on the Gee. We were in luck. It worked and Bill quickly plotted a fix. So far, so good. Next we turned the Gee box off and I called up the VHF guardian angels on Channel ‘C’ – the distress frequency. At once there came that voice of reassurance, asking me to transmit for a little longer. She then gave us a course to steer and shortly afterwards said, ‘Friends are with you.’ Bill and I took a good look round and spied a Beaufighter, which stayed with us until we reached the English coast. We motored on eventually and got down fairly expertly which drew from the imperturbable Mr Hickox the comment, ‘Good Show’. Praise indeed. Shortly after this effort came another indication that Lady Luck was on our side. We were briefed for yet another trip to Berlin, but during the afternoon the raid was cancelled and a short-range attack on a Ruhr target was substituted. This was to be an all-Mosquito affair, led by 105 and 109 Squadrons. Our CO, Wing Commander Roy Elliott, decided that this was an opportunity for new crews to have a go and Bill Hickox and I were stood down in favour of two ‘makey-learns’. We had air-tested the aircraft that morning and were satisfied that it was in all respects serviceable. Yet as the Mosquito lifted off at night and entered the area of blackness just beyond the upwind end of the flare path both engines failed and there came the dreadful sound of a crash as the aircraft hit the ground. Both crewmembers were killed. Would this have happened if Bill and I had been on board? We shall never know. On the night of 2/3 December 627 Squadron lost its first Mosquito when Flight Sergeant Leslie ‘Doggie’ Simpson and Sergeant Peter Walker who were on their first operation since joining from 139 Squadron, failed to return from a raid on Berlin by 458 aircraft. Peter Walker recalls: Before leaving the English coast it was found that the Gee set was unserviceable but it was decided to carry on using Dead Reckoning navigation with forecast winds. This proved to be highly dangerous as, instead of Southerly winds, it was later reported that the winds had veered to the North and strengthened. Apart from the occasional burst of flak nothing amiss happened until, 100 miles from Berlin, in the region of Magdeburg, a predicted burst of flak took out the starboard engine. Doggie Simpson decided to carry on to the target on one engine. At a much-reduced height and twenty minutes late on target Berlin was bombed and the aircraft turned for the journey home. Unfortunately there was no way of obtaining a visual pinpoint and those unreliable winds were used. At approximately 23.59 hours a terrific barrage of flak was encountered during which time the aircraft was continuously hit. The aircraft was then at a very low altitude with a considerable number of pieces missing from the airframe. After passing through this area, later presumed to be the Ruhr, we continued for a further 50 minutes when at 00.50 hours the aircraft was abandoned. ‘F for Freddie’ had flown 2 hours l0 minutes with both engines functioning and 4 hours 2 minutes on a single engine, a total of 6 hours 12 minutes. The approximate fuel consumption was 70 gallons per hour.97 Although it was a tight squeeze in the bomb bay, by early 1944 suitably modified B.IV Mosquitoes were capable, just, of carrying a 4,000lb Minol bomb, which went by the more familiar names of ‘Cookie’ or ‘Blockbuster’. To

Description: