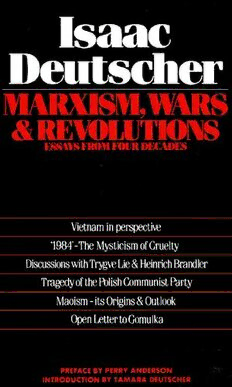

Marxism, Wars and Revolutions: Essays from Four Decades PDF

Preview Marxism, Wars and Revolutions: Essays from Four Decades

Isaac Deutscher Vietnam in perspective '1984' -The Mysticism of Cruelty Discussions with Trygve Lie & Heinrich Brandler Tragedy of the Polish Communist Party Maoism -its Origins & Outlook Open Letter toGomulka Isaac Deutscher Verso lsAAC DEUTSCHER was born in 1907 near Krakow and joined the Polish Communist Pany in 1926. After his expulsion in 1932, he maintained his opposition to the general drift of Comintern policy in the 1930s. He moved to London in 1939 and continued his journalistic activity until 1946, devoting the rest of his life to historical research and the writing of books and essays. Isaac Deutscher's prolific output includes Stalin (1948); a trilogy on Leon Trotsky: The Prophet Armed (1954), The Prophet Unarmed (1959) and The Prophet Outcast (1963); The Unfinished Revolution (1967), The Non-Jewish Jew (1968), and numerous essays on Russia, China and contemporary com munism. Isaac Deutscher died in 1967. TAMARA DEUTSCHER, who has edited several collections of her husband's essays, is herself a writer specializing in Soviet and East European affairs. v Marxism, Wars and Revolutions: Essays from Four Decades Edited and introduced by Tamara Deutscher With a preface by Perry Anderson British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Deutscher Isaac Marxism, Wars and Revolutions I. Communism - 1945-- Case studies 2. Communist state - Case studies I. Title 320.5'32'0722 HX44 First published 1984 • Tamara Deutscher and Verso 1984 Verso 15 Greek Street London WI Filmset in Garamond by PRG Graphics Ltd Redhill, Surrey Printed in Great Britain by The Thetford Press Ltd Thetford, Norfolk ISBN 0 869010954 978-0-86091-803-5 Contents Preface by Perry Anderson Introduction by Tamara Deutscher XX:l I. The USSR 1. The Moscow Trial 3 2. 22 June 1941 18 3. Reflections on the Russian Problem 26 4. Two Revolutions 34 II. Cold War 1. The Ex-Communist's Conscience 49 2. '1984' - The Mysticism of Cruelty 60 3. The Cold War in Perspective 72 III. Europe 1. The Tragedy of the Polish Communist Party 91 2. An Open Letter to Wladyslaw Gomulka 128 3. Dialogue with Heinrich Brandler 132 4. Conversation with Trygve Lie 169 IV. China 1. Maoism - Its Origins and Outlook 181 2. The Meaning of the 'Cultural Revolution' 212 V. Marxism and Our Time 1. The Roots of Bureaucracy 221 2. Marxism in Our Time 243 3. Violence and Non-Violence 256 4. On Socialist Man 263 Preface Isaac Deutscher, who died seventeen years ago, was one of the greatest socialist writers of this century. He was a Marxist and a historian. But in the way in which these two vocations were con nected in his work, the place he occupies in the literature of each is unlike any other. Deutscher's fame rests above all, of course, on his political biographies of Stalin and Trotsky - two masterpieces on the fate of the Russian Revolution. In them, all Deutscher's powers were concentrated on the object of his life's study; and it is there that readers new to his legacy will continually start. This volume serves a complementary purpose. The collection of essays and addresses that it contains gives us the best intellectual portrait of the biographer himself - that is, of Deutscher as a mind. For the essayist, in the nature of the genre, could speak more directly and personally, and over a more various and unexpected range of topics, than the historian: subjective experience and conviction find greater expres sion in these interventions than in the major objective reconstruc tions of the past themselves. From them, we can see Deutscher as he was, a much more complex and multi-dimensional figure than the terms by which he became best known in his life-time would suggest: not simply a scholar, but a thinker, of the Left; and not only a commentator on events, but a committed participant in them. Thanks to the care of Tamara Deutscher, the symposium of texts below - which includes several that have never before been published, or collected, in English - presents a more comprehen sive view of Isaac Deutscher, as a fighter and a critic, an intellectual and militant, than any previously available. What do they reveal? In the first instance, through their prism, the original context that nurtured Deutscher comes into view. The uni versalism of the mature writer tended to conceal these origins: but it was in fact a very. particular regional experience that made possible the later cosmopolitanism. However, like that of another master of English prose, Joseph Conrad, his Polish past long lay partly hidden from sight, and can easily be misunderstood. Deutscher was born in the province of Krakow in 1907, and as a boy grew up in natural sympathy with Polish traditions of literary experiment and political emancipation. But his family was not from the patriotic gentry, but from the Jewish middle-class, where his father owned a printing business; and his youthful politics were early on socialist. A genera tion earlier, Rosa Luxemburg had come from a similar background in the neighbouring province of Lublin, where her father was in the timber-trade. 1 Like her, Deutscher entered the Polish revolutionary movement while still in his teens, joining the Polish Communist Party in early 1927. Between the experiences of the two lay, of course, the change that had confounded one of Luxemburg's life long perspectives - the independence of Poland. But as Deutscher explains in The Tragedy of the Polish Communist Party, the pre dominant tradition in the political milieu in which he became a militant was still Luxemburgist. The way in which that tradition was weakened, compromised and finally snuffed out forms, in fact, the leitmotif of his moving evocation - at once analytically sharp and acutely felt - of the fate of pre-war communism in Poland. Deutscher's own formation, however, was in close continuity with Luxemburg's heritage. From it he took its moral independence, its spontaneous internationalism, its uncompromising revolutionary spirit - a Marxism that was as classical in ease with the theory of historical materialism (Luxemburg had been the first Marxist to criticize the schemas of reproduction in Capita~, as it was vigorous in its connection with the practical life of the workers' movement. To these historical bequests there was added a specific geogra phical endowment as well. Poland lay between Germany and Russia, the two great powers that had decisively shaped - or misshaped - its destiny since the days of Napoleon. Luxemburg's career as a socialist had passed in the ambience of all three nations: organizing the clandestine labour movement in Poland from her student days, intervening in the debates of the Russian movement during the Revolution of 1905-1907, and leading the Left in the German move ment in the final decade of her life. Nor was her case an isolated one. Her contemporary Karl Radek, from Brest, was equally at home from Bremen to Moscow. For a socialist of Deutscher's generation, Versailles Poland no longer afforded this kind of possibility. But the ' The principal difference between the two was the language spoken at home: Polish in Luxemburg's case, Yiddish in Deutscher's. geopolitical position of the country still ensured that any Polish Marxist would be formed against the imm~diate horizons of events in Germany and Russia: in some ways more so than ever, as the October Revolution had now given birth to the USSR, the first workers' state in the world, while the Communist International focused its greatest hopes and efforts on a second breakthrough in Weimar Germany. It was thus quite logical that Deutscher's service in the Polish Communist Party should have come to an end, not over national issues as such - tortuously mishandled though these were by the Party under Soviet pressures, as his retrospect recalls - but over the growth of fascism under the neighbouring capitalist state. In 1932, he formed part of a minority opposition that attacked the sectarian passivity of the German Communist Party, imposed by the Stalinist leadership of the Comintern, towards the rise of Nazism - while at the same time criticizing the results of the same 'third period' line, and the bureaucratic regime that accompanied it in the Polish party. These positions came to coincide with those of Trotsky in exile: and Deutscher was expelled from the Polish Communist Party, as Trotsky's warnings of the terrible threat posed by Hitler's gangs to the European working-class reached their crescendo. If Germany was the immediate occasion for Deutscher's break with the official Communist movement, Russia was to be the abiding concern of his mature work as a Marxist. Already in 1931 he had travelled to the USSR for the Polish party, and witnessed at first hand the ravages of collectivization and famine, as well as the industrial feats of the first five-year plan. By this time, the policies of the Third International were entirely subordinated to the twists and turns of the Soviet party leadership, as Stalin remorselessly consolidated his power in Russia. With the victory of Nazism in Germany in 1933, the direction taken by the Russian Revolution would be decisive for the fate of the European labour movement as a whole. The text that opens this collection, the pamphlet Deutscher wrote in October 1936 on the first of the great Moscow Trials, set the agenda for the rest of his life. Written with searing indignation, his hand - as Tamara Deutscher puts it - 'trembling with rage', Deutscher's protest nonetheless already displayed some of the distinctive qualities that were to mark his later work as a Marxist historian. Thus he was not content with dismantling the circumstantial absurdities of Stalinist 'evidence' at the Trial: even more conclusively, he dwelt on the psychological impossibility of an alleged 'terrorism' that abased itself before its accusers, an audacious 'conspiracy' collapsing into abject