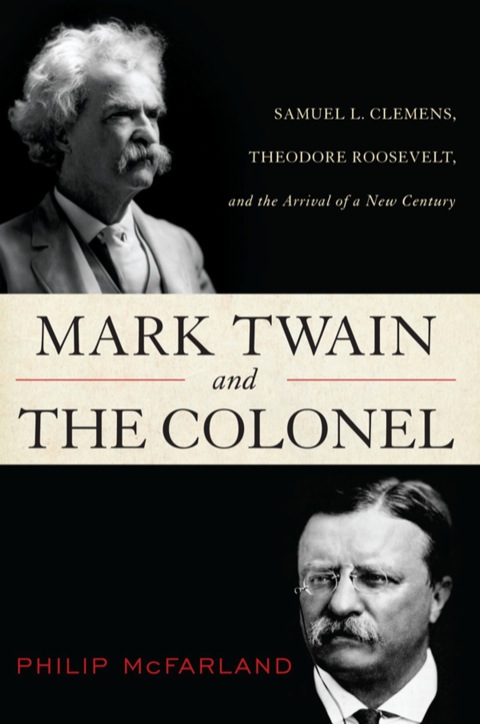

Mark Twain and the Colonel: Samuel L. Clemens, Theodore Roosevelt, and the Arrival of a New Century PDF

Preview Mark Twain and the Colonel: Samuel L. Clemens, Theodore Roosevelt, and the Arrival of a New Century

For most of a decade Mark Twain lived in Europe, returning at last to America and a joyous welcome on an October night in 1900. Ten years later, in the spring of 1910, he returned once more, only days before his death, carried down the gangway as reporters on the New York piers waited, yet again, to welcome him home a final time. In those two decades last of the nineteenth and first of the twentieth our modern nation was formed. Men whose names have become legendary Rockefeller, Carnegie, Edison, Wright, Ford exemplified the great changes taking place in America at the time. But only one name rivaled Mark Twain s in the love of his countrymen. Theodore Roosevelt dominated the politics of the era just as the author of Huckleberry Finn dominated its culture. The celebrities were well acquainted, and in public neither spoke ill of the other. But Roosevelt once commented in private that he would like to skin Mark Twain alive, and the humorist recorded his own opinion (although not for public consumption until later) that Roosevelt was far and away the worst President we have ever had. Philip McFarland s Mark Twain and the Colonel describes the prickly relationship between these beloved figures by focusing on two tumultuous decades of abiding relevance, decades to which no Americans were more responsive than Colonel Roosevelt of San Juan Hill and the humorist Mark Twain.