Table Of ContentPenguin Books

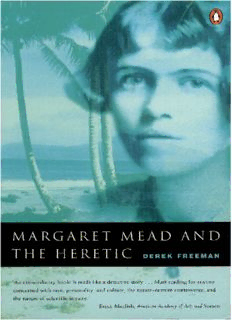

Margaret Mead and the Heretic

Derek Freeman was born in Wellington, New

Zealand, in 1916. After studies in the Universities

of New Zealand and London he took his PhD in

anthropology at the University of Cambridge in

1953. Since 1955 he has been an Australian citizen

and a member of the Research School of Pacific and

Asian Studies in the Institute of Advanced Studies

of the Australian National University. As well as

having done extensive field research among the

Iban of Borneo, he has taken a special interest in

the history of biology and anthropology. He has

visited Samoa on seven occasions since 1940, and

spent six years working in various parts of the

Samoan archipelago. He has thoroughly investi

gated Margaret Mead's Samoan researches, both in

Manu'a (where she worked in 1925-26), and in her

field notes and other papers now held in the Manu

script Division of the Library of Congress in Wash

ington, D.C.

In 1964 he had detailed discussions with Mar

garet Mead when she visited the Australian

National University. In 1983 his formal refutation

of Mead's conclusions about Samoa was published

by Harvard University Press as Margaret Mead and

Samoa. It was given worldwide attention and led to

what has been called "the greatest controversy in

the history of anthropology". Today, Derek Freeman

and his wife Monica live in Canberra, where

Freeman, as an Emeritus Professor, is actively

working towards the realization of a new anthro

pological paradigm.

What is heresy, and who are the heretics? The word itself

is instructive. The Greek term hairesis originally meant a

taking or conquering, especially the seizing of a town by

military force. But the meaning shifted to indicate the

taking for oneself, that is, the making of a choice. A heretic

is one who prefers to make a personal choice rather than

accept and support the view held by the majority of his

community.

T. W. Organ, Third Eye Philosophy: Essays in East

West Thought, Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio,

1987

DEREK FREEMAN

MARGARET

M E A D

AND THE

HERETIC

The making and unmaking

of an anthropological myth

Penguin Books

Penguin Books Australia Ltd

487 Maroondah Highway, PO Box 257

Ringwood, Victoria 3134, Australia

Penguin Books Ltd

Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

Viking Penguin, A Division of Penguin Books USA Inc.

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Canada Limited

10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd

182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand

First published as Margaret Mead and Samoa by Harvard University Press 1983

Published as Margaret Mead and Samoa, with addendum to preface, by Penguin Books 1984

Reissued as Margaret Mead and the Heretic, with new preface, by Penguin Books 1996

10 9 8 7 6 54 3 2

Copyright © Derek Freeman, 1983, 1984, 1996

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright

reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored

in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form

or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior

written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this bciok.

Made and printed in Australia by Australian Print Group

The line quoted on pxiii) of the preface from Robert Bolt's play, The Common Man, is reprinted by

permission of Heinemann Educational, a division of Reed Educational and Professional Publishing Ltd.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Freeman, Derek.

[Margaret Mead and Samoa]

Margaret Mead and the heretic.

Includes index.

ISBN 0 14 026152 4.

1. Mead, Margaret, 1901-1978.2. Ethnology-Samoa. 3. Samoa-Social life and customs. I. Title.

II. Title: Margaret Mead and Samoa.

306.089994

For David Williamson

Foreword

MEAD'S SAMOA AS OF 1996

MY BOOK of 1983 is being republished, under a new title, to

coincide with the staging in Australia of David Williamson's play

Heretic. Since it was first published, over thirteen years ago, our

knowledge of Margaret Mead's fieldwork in Samoa, and in

particular our knowledge of what befell her on the island of Ofu

in 1926, has been radically transformed. It becomes vitally

important therefore to present a brief account of what historical

research has finally revealed about Margaret Mead's much dis

cussed Samoan researches of the mid 1920s.

In my book of 1983 evidence was amassed to demonstrate that

Margaret Mead's conclusion in Coming ofA ge in Samoa, because

it is at odds with the relevant facts, cannot possibly have been

Foreword vii

correct. It had become apparent that the young Margaret Mead

had, somehow or other, made an egregious mistake. At that time,

however, no credible explanation could be given of how this

mistake had come to be made.

I noted then that the explanation most consistently advanced

by the Samoans themselves for the magnitude of the error in

Mead's depiction oftheir sexual morality was, as Eleanor Gerber

had reported in 1975, "that Mead's informants must have been

telling lies in order to tease her". But I then went on to say that

plausible as this might seem, we could not "in the absence of

detailed corroborative evidence be sure about the truth of his

Samoan claim". In 1983, any such "detailed corroborative evi

dence" was entirely lacking. The situation dramatically changed

however in 1987 when I revisited American Samoa in the

company of Frank Heimans, the Australian documentary film

maker.

At that time, the Secretary for Samoan Affairs of the Govern

ment of American Samoa was Galea'i Poumele, a high chief from

Fitiuta in Manu'a. When I called on Galea'i Poumele in his office

in Pago Pago on 12 November 1987, he announced that he would

be flying with us to the island ofTa'u (the site of Mead's research

headquarters in 1925-1926) where there was someone in the

village of Fitiuta whom he wanted us to meet. When we reached

Fitiuta the next morning, we were approached by a formally

dressed, dignified Samoan lady, who had obviously been expect

ing us. Having greeted Galea'i, she announced that she had

something to say, and would like to have it recorded on video so

that all might know of it.

She was, to my great surprise, Fa'apua'a Fa'amu, Margaret

Mead's foremost Samoan friend of 1926, and at 86 years of age

still mentally alert and active. Fa'apua'a Fa'amu, although I

had read about her in Margaret Mead's Letters from the Field

of 1977, was someone I had never previously met. Nor had I

been in any kind of communication with her. During my pre

vious visits to Manu'a she had, unknown to me, been living in

Hawaii. She had gone there in 1962 with her husband Telemu

Togia and all but one of their seven children. It was only on

the death of Telemu Togia in June 1986 that she decided to

viii Foreword

return to her birthplace. In March 1987 she had taken up

residence back in Fitiuta with her daughter Lemafai, the only

one of her children to have remained in Samoa.

The key excerpt from Galea'i Poumele's conversation with

Fa'apua'a Fa'amu on 13 November 1987, translated into

English, runs as follows:

Galea'i Poumele: Fa'amu, was there a day, a night or an

evening, when the woman [i.e. Margaret Mead] questioned

you about what you did at nights, and did you ever joke

about this?

Fa'apua'a Fa'amu: Yes, we did. We said that we were out

at nights with boys. She failed to realize that we were just

joking and must have been taken in by our pretences. Yes,

she asked, 'Where do you go?' And we replied, 'We go out

at nights!' 'With whom?' she asked. Then your mother,

Fofoa, and I would pinch one another and say, 'We spend

the night with boys, yes, with boys!' She must have taken

it seriously but we were only joking. As you know Samoan

girls are terrific liars when it comes to joking. But Mar

garet accepted our trumped up stories as though they were

true.

Galea'i Poumsle: And the numerous times that she ques

tioned you, were those the times the two of you continued

to tell these untruths to Margaret Mead?

Fa'apua'a Fa'amu: Yes, we just fibbed and fibbed to her.

Fa'apua'a had made this confession, she later explained, because

when she had been told by Galea'i Poumele and others about

what Margaret Mead had written about premarital promiscuity

in Samoa, she suddenly realized that Mead's faulty account

must have originated in the prank that she and her friend Fofoa

had played on Mead when they were with her on the island of

Ofu in 1926. Innocuous though it seemed at the time, it was a

prank, she had come to realize, which had had the unintended

consequence of totally misleading very many people about

Samoans. She had decided, she said, to set the record straight

by making a formal confession in the presence of the Secretary

Foreword ix

for Samoan Affairs about the way in which she and

Fofoa had totally misinformed Margaret Mead when she

questioned them about the sexual behavior of Samoan girls.

In 1988 Fa'apua'a's statements of 1987 were investigated in

great detail and her memory of other events of 1926 carefully

checked by Leulu Felise Va'a, who holds a PhD in anthropology

from the Australian National University, and is a lecturer in

Samoan language and culture at the National University of

Samoa. For Samoans, like Fa'apua'a Fa'amu, who are devout

Christians, swearing on the Bible is the most serious of sanc

tions. It is believed that the punishment for swearing falsely is

etemal damnation. On 2 May 1988, in a formally witnessed dep

osition, Fa'apua'a swore on the Bible that all parts of her testi

mony were true and correct.

In December 1989, my report on the testimony of Fa'apua·a

Fa'amu was published in the American Anthropologist, and, a

few months later, in British Columbia, I had the great good

fortune to meet Douglas Cole, a Professor of History at Simon

Fraser University, who is working on a definitive biography of

Franz Boas. Professor Cole generously presented me with copies

of the correspondence of Franz Boas and Margaret Mead for the

years 1925-1926 which he had obtained in the course of his own

researches. These, and the additional letters for 1927-1928

which I obtained from the archives of the American Philosoph

ical Society in Philadelphia (where the Boas papers are held),

contained much vitally significant information, and I was left in

no doubt at all about the importance of making a thoroughgoing

historical study of Mead's Samoan fieldwork.

Mead's Samoan fieldwork of 1925-1926 was conducted as a

National Research Fellow in the Biological Sciences of the

National Research Council of the USA. In 1991 I secured from the

archives of the National Research Council copies of all the doc

uments referring to Mead's tenure of this research fellowship, as

well as copies of her correspondence with the National Research

Council for the years 1925 to 1930. Then, in 1992, I flew from

Canberra to Washington to research thoroughly the relevant sec

tions of"the papers of Margaret Mead" in the Manuscript Division

of the Library of Congress. Among my principal discoveries were

Description:In 1928 Margaret Mead announced her discovery of a culture where free love flourished, and jealousy and adolescent turmoil were unknown. In this work Derek Freeman provides evidence that Mead made a series of errors in her analysis of the Samoan people. Over years of research, Freeman found the Samo