Marching Dykes, Liberated Sluts, and Concerned Mothers: Women Transforming Public Space PDF

Preview Marching Dykes, Liberated Sluts, and Concerned Mothers: Women Transforming Public Space

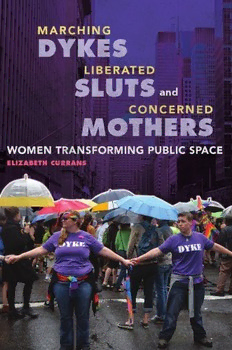

MARCHING DYKES LIBERATED SLUTS and CONCERNED M OTHERS WOMEN TRANSFORMING PUBLIC SPACE ELIZABETH CURRANS Marching Dykes, Liberated Sluts, and Concerned Mothers Marching Dykes, Liberated Sluts, and Concerned Mothers Women Transforming Public Space ElizabEth Currans © 2017 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Currans, Elizabeth, 1973– author. Title: Marching dykes, liberated sluts, and concerned mothers: women transforming public space / Elizabeth Currans. Description: Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifiers: lccn 2017011914 (print) | lccn 2017025041 (ebook) | isbn 9780252099854 (ebook) | isbn 9780252041259 (hardback) | isbn 9780252082801 (paper) Subjects: lcsh: Feminism—United States. | Protest movements— United States. | bisac: social science / Gender Studies. | social science / Women’s Studies. | history / United States / 21st Century. Classification: lcc hq1236.5.u6 (ebook) | lcc hq1236.5.u6 c87 2017 (print) | ddc 305.420973—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017011914 Cover illustration: New York City Dyke March, 2015. Photo by Elizabeth Currans. Background photo of Manhattan by Phillip Capper. Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments xiii Introduction: Regendering Public Spaces 1 Part I. resPondIng to danger, demandIng Pleasure: sexualItIes In the streets 1 Safe Space? Encountering Difference at Take Back the Night 21 2 Enacting Spiritual Connection and Performing Deviance: Celebrating Dyke Communities 41 3 SlutWalks: Engaging Virtual and Topographic Public Spaces 60 Part II. gendered resPonses to War: dePloyIng FemInInItIes 4 Demonstrating Peace: Women in Black’s Witness Space 91 5 Uncivil Disobedience: CODEPINK’s Unruly Democratic Practice 109 Part III. engenderIng CItIzenshIP PraCtICes: Women marCh on WashIngton 6 Embodied Affective Citizenship: Negotiating Complex Terrain in the March for Women’s Lives 135 7 Participatory Maternal Citizenship: The Million Mom March and Challenges to Gender and Spatial Norms 159 Conclusion: Holding Space: The Affective Functions of Public Demonstration 177 Notes 185 Works Cited 197 Index 215 Preface Sitting next to my computer as I write is a memo to “members of proposed settle- ment in class action lawsuit involving the 2004 Republican National Convention.” Within this document, I’m supposed to find myself in “Mass Arrest Subclass Six: August 31, 2004, on 16th Street between Union Square East and Irving Place, be- tween 7:00 p.m. and 10:00 p.m.” I was with seven others. Most of us were part of a direct action–oriented group created in response to the 2003 bombing of Iraq called ARISE, which I’ve written about elsewhere.1 We’d discussed the possibil- ity of arrest, left contact information with a local ally, and buddied up based on different comfort levels with risks of bodily harm and arrest. As part of the more risk-averse half of our group, I was paired with another graduate student, Frank. Our buddy system became particularly important once we arrived at Union Square, where we planned to take part in a street party. This party, one of many simultaneous protests around the city, sought to demonstrate collective playful- ness in the face of stern warnings from the New York City Police Department. We wanted to enact another way of being in the city and in the world, an impetus similar to the now iconic protests against the World Trade Organization (WTO) in Seattle and anarchist events worldwide.2 The party was short-lived; we hadn’t even moved a block out of the park before we were met by police in riot gear. As they closed in on us from both sides, Frank and I were among a group of people pushed up against a wall on the south side of 16th Street. As the police advanced, they told us to disperse, yet there was no place to go. This tactic, I now know, is called “kettling.”3 In front and on both sides of us were police holding orange netting; behind us was a concrete wall. I held Frank’s hand as we were pressed tighter and tighter against the wall. My feet left the ground as I was mashed be- tween other bodies, and I lost hold of Frank’s hand. I don’t recall how we peeled viii . preface ourselves apart and found ourselves sitting on the sidewalk in small groups with arresting officers assigned to us. I do remember Frank being led away with some other men. I remained on the sidewalk with two other women from our group. As we were searched, we watched people being led away with their hands bound behind them. Soon we too were cuffed, herded onto waiting buses, and driven to a holding facility at Pier 57. There I was separated from the rest of the women in my group and spent ten hours inside a large cage made out of chain- link fencing on the grease-covered floor of a former airplane storage facility. We women watched from our cages as the men were led, group by group, out of the facility. We later learned from a guard that the city had more official facilities for holding men, which is why they could be booked and moved through more quickly than women. After fifty-two hours I was released to find my seven friends and one friend’s mother waiting outside. We took the subway uptown, giddy with exhaustion. Frank and the other two men in the group serenaded us with pirate-inspired songs as we walked from the subway station two blocks west and five floors up to my friend’s apartment. I begin with this story to set up a few important features of the time period during which most of the events discussed in this book occurred. First, the na- tion was at war, and military aggressions abroad were at the forefront of public discussions. (As I write in 2016, we’re still at war, a fact that seems so normal as to be unremarkable.) Then, many people were actively engaged in defending or contesting U.S. military presence in Iraq and Afghanistan, as chapters 4 and 5, focused on Women in Black and CODEPINK, explore in more depth. Second, protesting was a contested activity fraught with risk of arrest and abuse by by- standers. This affected how people approached their public presence and the tactics they employed. Protesting was also not new. As Don Mitchell and Judith Butler each reminds us, public space is not given; it is always the result of struggle.4 The state is also closely involved in regulating who can say what and when and where they can say it.5 Third, and most important for this text, gender matters even in mixed-gender events focused on seemingly ungendered issues. Our gen- dered socialization affects how we interact with others. Additionally, criminality is primarily associated with men, especially men of color and working-class white men. Our judicial and prison systems, like most social institutions, also rely on a rigid gender binary that not only treats men and women differently but also fails to recognize genders that depart from narrow understandings of masculine men and feminine women. All these factors affect why and how women engage in protest activities and how people respond to women’s public presence. In the United States and globally, 2004 was a particularly fraught moment. Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were at the forefront of many people’s minds; there was still widespread debate about how the United States should respond internation- preface · ix ally and domestically to the attacks of September 11, 2001; and it was a presidential election year complete with large conventions for both major political parties. Not only did the U.S. media have a lot to say about such issues, but commentators around the globe did too. Like people in the United States, people in numerous other countries took to the streets and published commentary in newspapers and magazines addressing U.S. militarism and their hopes and fears for the U.S. election. Accordingly, the demonstrations described in this book provided an opportunity to think about how women-dominated groups addressed a variety of issues at a time when civil liberties were being renegotiated. Feminism in the Twenty-First Century Activists in 2004 struggled with long-held anxieties about feminism and activ- ism, as well as the issues particular to the post-9/11 era. The comment below from Heather, a forty-four-year-old white heterosexual officer in the Twin Cities (Minnesota) chapter of the Million Moms March, highlights some of the per- ceptions of activism in U.S. culture at the time, views that have changed little in the past decade. I hate to say that us being active as moms is a way of us keeping our role, but it is less threatening for a lot of women to be out there marching as a mom than marching as an activist. It’s my guess that a lot of Million Moms don’t consider themselves activists. And for me, I think I got to be more comfortable using [the term “activist”] being involved in the peace movement, where to be an activist is really something you work towards, where with the Million Moms it’s more like we’re volunteers. There is a real difference there. Obviously, in the peace movement you’re volunteers too. But really you’re a peace protester. You’re a peace activist. You’re an antiwar activist. And we’re Million Moms. We’re volunteers. We’re or- dinary people. . . . It’s a less threatening way to be seen in the general public, it’s a more open and inviting way to bring more people in. As her comments indicate, “activist” is not a label all people are willing to accept even if the work they do is seen by others as activist. Additionally, people who might be seen by outsiders as activists have distinct relationships to the term and to cultures of respectability. Antiwar protesters see themselves as contesting the status quo and therefore are more likely to embrace a label such as “protester” or “activist.” The Million Moms, who enter the political sphere in the name of children, are invested in maintaining ties to people who see activists as outside of acceptable norms. This respectability might have felt more important in 2004 than in early 2001. Media scholar Marita Sturken explains: “September 11 has become a marker of change, the day when the society we live in was divided into