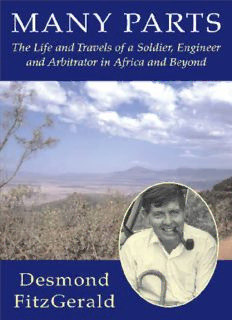

Many Parts: The Life and Travels of a Soldier, Engineer and Arbitrator in Africa and Beyond PDF

Preview Many Parts: The Life and Travels of a Soldier, Engineer and Arbitrator in Africa and Beyond

MANY PARTS MANY PARTS The Life and Travels of a Soldier, Engineer and Arbitrator in Africa and Beyond Desmond FitzGerald The Radcliffe Press ⋅ LONDON NEW YORK Published in 2007 by The Radcliffe Press 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU In the United States and in Canada distributed by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St Martin’s Press 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Desmond FitzGerald, 2007 The right of the estate of the late Desmond FitzGerald to be identified as the licensor of this work has been asserted by the licensor in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978 1 84511 306 3 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress Catalog card: available Typeset in Sabon by Oxford Publishing Services, Oxford Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall Contents Acknowledgements vi Preface viii Introduction ix Lineage xi Part I: Tale of Four Families 1 1. My immediate family 3 2. England and India 20 3. My school years in England, 1925–35 29 4. Further education: the RMA, SME and Cambridge 66 Part II: Away to the War 79 5. Phoney War 81 6. Dunkirk, Leeds and Skegness 91 7. Round Africa convoy 100 8. Middle East posting 114 9. Tripoli, Tunis and preparing for Italy 126 10. Italy and training for Europe and Overlord, 1943 135 Part III: Peacetime Soldiering 157 11. Military service in East Africa, 1945–48 159 12. Back in the UK 175 Part IV: Kenya: my second career, 1955–99 193 13. Down to earth 195 14. Family life and DF&A, 1965–76 218 15. Nomad roaming from place to place, 1976–81 240 16. Life on Ol Olua Ridge and Kamundu, 1979–89 258 17. The last lap: 1990–2000 267 Index 271 v Acknowledgements The end of the Second World War and then 40 or more years of silence on the part of most participants. Who wants to provoke that glazed look that labels you the bore of the century if you dare reminisce? History books, of course, there are in plenty; but you don’t have to read them, and for that matter, who does? Then gradually one senses a thaw. Don’t ask why, but young people begin to listen, actually to invite one to open up. They don’t actually ask the dreaded question: ‘What did you do?’, but if you tell them a good story they start asking for more. One’s family, of course, are the most curious. I remember wondering about my father, who married my mother when he was 40. Did life really start for him in 1915? What was he up to during all that lost time? No good, no doubt. So it is with our daughter Katie, although she has already heard most of what follows during her 30 odd years. Our grandchildren are not old enough yet to be curious; Charlie wants eventually to own my ceremonial sword, and so he shall, one day. My story is meant mostly for their mother and for them when they are old enough to read it – and perhaps their children. What about a wider audience? This was where the idea of a memoir became exciting. I had the luck to befriend a young Irish colleague in the company for which I work, named Sue Lawless. She liked my tales (anecdotes you could call them, though I dislike the word), and kept on encouraging me to put them on tape. I might have done so at that, if I had had her beside me when I recorded; but she went and got married and left for Uganda, and I could not relate anything just into thin air. It was not that Sue was interested in the war as such; in fact the idea of war repels her. What excited her were the tales of human interest. She loved the sad story of Lucy the hen – she even wanted me to tell it at her wedding. It was her particular enthusiasm that made me think that even the story of vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS my childhood might attract a wider audience; but others, particu- larly my wife Barbara, have encouraged me to prune that part very thoroughly. I am leaving that to an editor. Sue Lawless, then, is responsible, if not for the memoir, for the enlarged form it has taken. Barbara, along with Sarah Cape, Bridget Evans and Joanna Hechle (who have been typing it) is reading it. They have all kept their opinions of it very much to themselves. Bridget, when in a moment of despair I threatened to bin the whole thing, said she thought that would be a pity – otherwise, silence. Barbara is my critic. She would like to have typed it, but with all her activities, including coping with my business correspondence, there would never be time. I would not be writing it at all if it were not for her. She is the one to whom I owe it all. I owe a deep debt of gratitude, of course, to the ladies who have actually taken on the onerous task of interpreting my awful writing and typing it. I am especially grateful to my two sponsors, my ex-brother-in-law W. R. (Bill) Horne who put up most of the funding and my ex-wife Buff (Elizabeth) FitzGerald who also contributed. I must also acknowledge the involuntary help I have had from other amateur authors. I’ve collected a little library of books of this kind, and have rather shamelessly plundered the best of them for ideas on style and construction. I am particularly grateful to Hugh Holmes, John Millard (who has read and commented on the war section) and Michael StJohn, whose books I treasure and hope to emulate. The late Roger StJohn’s family reminiscences have also been an enormous help. My son-in-law, Philip McLellan, told Ian Parker about my book and he expressed interest. When he had read the first draft Bridget passed to him he told me he would like to edit it. He noted that the book stopped in 1955, 45 years ago. ‘Why?’ I said I was thinking of stopping it in 1964, the year of my second marriage. ‘That is not much of a compliment to Barbara.’ ‘Well what can possibly interest anyone in an account of domestic ups-and-downs, let alone bliss?’ ‘What about your grandchildren, and your great grandchildren?’ That’s it then, the whole story as edited by Ian. So, here’s to Sue and Sarah and Bridget and Jo, and to Hugh and John and Michael and Roger and Ian; and most of all to Barbara, my wife, for being my critic and having to put up with me for so long and for enabling me to survive happily to tell the tale. vii Preface Henry Ford I opined: ‘History is bunk’. Tony Blair seems to hold the same view. ‘Call me Tony’ he bleats. Why not ‘Blair’ for God’s sake? What’s wrong with a distinguished Highland Scottish clan name? I am Desmond John Otho FitzGerald. At my prep school I was ‘FitzGerald’. My friend, John Gaskell, had an elder brother there, and was therefore known as ‘Gaskell Minor’. Nobody addressed us as ‘Desmond’ and ‘John’. Similarly, at Wellington. I believe they got this right. Now I am mostly ‘Desmond’, even in the office. This marks me as a person, that’s all. FitzGerald links me to a family 1000 years old, and to 1000 years of history. It is nothing to boast about, but something surely to live up to? That is why I have written a few paragraphs about my Geraldine and Goodbody forebears. viii Introduction Apologies all round. Clinton apologizes for slavery. Aus- tralians say sorry to the Aborigines. Her Majesty of the United Kingdom, it is true, bucks the trend over Amritsar and the Emperor of Japan dissatisfies the British survivors of Japanese prisoner-of-war camps; but we lesser lights are expected to follow the fashion and don sackcloth and ashes. The FitzGeralds, including the Glin clan, have nearly a millen- nium of misbehaviour to account for. A FitzGerald was one of Strongbow’s lieutenants in the 1169 invasion of Ireland – out- rageous aggression – followed by the illegal seizure of great tracts of land in southwest Ireland. They even had pretensions to (petty) kingship. The FitzGeralds, it is true, didn’t have to pretend not to be English – they were not; but to claim to be Irish, that was another matter. They were, are, Normans, with roots in Italy and the Mediterranean islands – ‘not one of us’ in the recent words of a truly Irish lady. Some of the FitzGeralds, the Kildares for example, sucked up to the English/Hanoverian monarchs and became earls and dukes. Thank God we Glins do not have to plead guilty to that; but what about our adoption of the Protestant religious rite, just to hang on to what was left of the lands we had pinched? Tut tut! Nearer to the present, we Glins fell into the bad habit of joining up and fighting British wars. There were FitzGerald officers in George III’s household brigade; and more recently still my own father fought in the second Anglo–Boer war. He could have been forgiven for this if he had realized he was fighting the oppressors of the South African Bantu, but he did not. He thought he was fighting for Queen and Country. How confused he was! He then compounded his errors by joining the colonialists in East Africa and became part of a mercenary African army, the King’s African ix

Description: