Male trouble PDF

Preview Male trouble

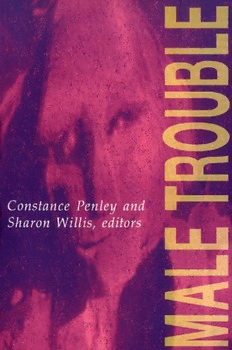

Male Trouble A camera obscura book MALE TROUBLE Constance Penley and Sharon Willis, editors PRIVATE SCREENINGS Television and the Female Consumer Lynn Spigel and Denise Mann, editors CLOSE ENCOUNTERS Film, Feminism, and Science Fiction Constance Penley, Elisabeth Lyon, Lynn Spigel, and Janet Bergstrom, editors Male Trouble Constance Penley and Sharon Willis, editors University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis London Collection copyright 1993 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota Parveen Adams, "Per Os(cillation)," reprinted from James Donald (ed.), Psychoanalysis and Cultural Theory: Thresholds (New York: St. Martin's Press; London: Macmillan Education Ltd., 1991), pages 68-87; by permission. Material from Camera Obscura, volumes 17, 19, and 25-26, © The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988, 1989, and 1991, respectively. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 2037 University Avenue Southeast, Minneapolis, MN 55455-3092 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Male trouble / Constance Penley and Sharon Willis, editors. p. cm. — (A Camera obscura book) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8166-2171-3 (hc : acid-free) ISBN 0-8166-2172-1 (pb : acid-free) 1. Men in motion pictures. 2. Sex role in motion pictures. 3. Rubens, Paul, 1953- . I. Penley, Constance, 1948- . II. Willis, Sharon, 1955- . III. Series PN1995.9.M46M27 1993 791.43'652041-dc20 92-25407 CIP The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. Contents Introduction Constance Penley and Sharon Willis vii Per Os(cillation) Parveen Adams 3 Fellowdrama Ray Barrie (with introduction by Mark Cousins) 27 Masochism and Male Subjectivity Kaja Silverman 33 Male Hysteria and Early Cinema Lynne Kirby 67 Male Narcissism and National Culture: Subjectivity in Chen Kaige's King of the Children Rey Chow 87 DOSSIER ON PEE-WEE'S PLAYHOUSE The Cabinet of Dr. Pee-wee: Consumerism and Sexual Terror Constance Penley 121 The Playhouse of the Signifier: Reading Pee-wee Herman Ian Balfour 143 "Going Bonkers!": Children, Play, and Pee-wee Henry Jenkins III 157 The Sissy Boy, the Fat Ladies, and the Dykes: Queerness and/as Gender in Pee-wee's World Alexander Doty 183 v vi Contents Masquerading as the American Male in the Fifties: Picnic, William Holden and the Spectacle of Masculinity in Hollywood Film Steven Cohan 203 "Crisscross": Paranoia and Projection in Strangers on a Train Sabrina Barton 235 Disputed Territories: Masculinity and Social Space Sharon Willis 263 Melodrama, Masculinity, and the Family: thirtysomething as Therapy Sasha Torres 283 Contributors 305 Index 309 Introduction Constance Penley and Sharon Willis Male Trouble is a very different volume from the special issue of Cam- era Obscura on which it is based. Not only has new material been added but the context in which it appears has changed dramatically. When the issue came out in 1988 the feminist debates about masculini- ty were already well under way and beginning to take specific shapes. Although some critics and theorists felt the study of masculinity was as crucial as that of femininity, others expressed consternation about what it meant for feminists to be giving so much attention to the com- plex, heterogeneous, and conflicted construction of masculinity at a moment when it was becoming clear that renewed, concerted an- tagonisms toward feminism were legitimating numerous attacks on women's equality and freedom. Or, as some put it even more strongly, wasn't there a danger that a theoretically sophisticated study of mascu- linity, which would necessarily involve positing male subjectivity as nonmonolithic and even capable of positive or Utopian moments, could entail a significant digression from a feminist project that remains un- derdeveloped in its attention to differences among women? The Camera Obscura issue aimed to contribute to the increasingly animated discussions on masculinity within feminism and gay studies. These discussions and debates suggest that most found the risk of focusing on masculinity more than worth taking, and in fact crucial to understanding a world where power is divided unevenly along gen- dered lines. Male Trouble thus appears in a newly redefined territory of gender relations, a territory mapped by the burgeoning of feminist work on masculinity but also by events that have marked the public conscious- ness and demonstrated once again the great gulf between feminists, in their claims for women's equality and self-determination, and those who believe those claims to be illegitimate. The list of those traumatic yet galvanizing events is a long one, and because the media representa- tion has tended to put mostly women on one side of the divide and mostly men on the other, the issues tend to get trivialized as successive vii viii Introduction episodes of a spectacularized and romanticized "battle of the sexes." So too, the media's tendency to structure these events as melodrama or soap opera versions of the battle of the sexes often means that differ- ences other than sexual ones get lost unless they also can be made into the stuff of melodrama, as was, for example, the narrative of Clarence Thomas's rise out of rural poverty into national prominence. These events—all of which, we are claiming, demonstrate the urgen- cy of examining male subjectivity—include, to be sure, the Clarence Thomas-Anita Hill hearings, in which for the first time in this country an issue of sexual politics claimed national attention through minute- by-minute television coverage; the media pairing of the William Kenne- dy Smith and Mike Tyson rape trials, which raised serious questions about the judicial system's capacity to deal adequately with the com- plexities of race, class, and gender as well as about the media's own ca- pacity to treat these issues without sensationalism; the steady erosion of reproductive rights; a dramatically deteriorated economy, which al- ways exacerbates sexual and racial scapegoating; Supreme Court deci- sions that follow the lead of the Reagan and Bush administrations in dismantling affirmative action; the Gulf War's construction of national identity as a virile, aggressively posturing masculinity; and the media prominence of a men's movement whose appeal is a nostalgic return to a reactionary and retrograde patriarchal masculinity as a defense against a debilitating femininity. At the same time as women are losing ground some men too are the objects of an escalated violence, as we can see in the alarming rise of gay bashing as well as systemic violence against African-American men. Because the editors of this volume are also professors, we have to include in this list the right-wing and media recruitment of Camille Paglia — in a tide of simplistic conservative at- tacks on "political correctness" —to trivialize or quash the nascent ad- vances of feminists in the academy. And because we are professors of film, we have to add the storm of media protest against Thelma and Louise that accompanied feminist debates about its political value as well as its runaway popularity with women audiences. Although the topic of this book is "male trouble" readers will find very little internal struggle over the now rather thoroughly discussed question of "men in feminism," or who gets to speak about masculini- ty. Although it is true that one recurring theme in this volume is straight masculinity (usually straight white masculinity) caught between fear of women and fear of homosexuality, the essays printed here aim to ex- amine the structure and bases of those fears rather than hesitating over the value of turning our attention to them. The book opens with four essays that introduce and explicate the recurring theoretical concerns of the volume. Not coincidentally, all of Introduction ix them examine masculinity by taking up psychoanalytic categories usually associated with femininity: hysteria, masochism, and narcis- sism. The idea is not simply to reverse these terms and "apply" them to masculinity. Rather, what we see here is a continuation of a move already begun by Freud and renewed by Lacan to understand these psy- chical positions or states as descriptive of subjectivity itself, rather than characterizing a uniquely feminine subject position. So too, the empha- sis here on understanding masculinity through hysteria, masochism, and narcissism represents a move away from a sometimes narrow view of masculinity as structured primarily around voyeurism and fetishism. Such a view assigned too much masterful agency to the position of the male voyeur or fetishist—a position often theorized over the last fifteen years as the position of cinematic spectatorship—with a consequent pacification of the position of the female viewer or character, reduced to "to-be-looked-at-ness." What is also apparent from the first four essays is the urgency of the wish to move toward an understanding of the ways the psychical for- mations and positions described by psychoanalysis are already social as well. In "Per (Os)cillation," for example, Parveen Adams shows that Freud in fact has no account of the fixing of sexual positions in relation to the femininity and masculinity that are supposed to be constituted by the Oedipus complex. Adams uses Freud's claims about masochism in "A Child Is Being Beaten" to demonstrate the arbitrariness in the way he assigns certain forms of the fantasy to men and others to women. She sees the same arbitrariness at work in Freud's attempt to show how the multiple possibilities of identification available for the subject get channeled into the relatively stable sexual positions called "masculini- ty" and "femininity." Where then, she asks, "do masculinities and femi- ninities come from?" If Freud gives no theoretical proof of how these sexual positions are arrived at, he does give some idea of what mascu- linity means for him in three anecdotes, cited by Adams following Neil Hertz, in which it is clear that Freud's own identification is with a scien- tific discourse culturally designated as masculine. For Kaja Silverman, too, the psychical and the social are entirely bound up with each other. In "Masochism and Male Subjectivity" she, like Adams, questions the way Freud asserts rather than proves the sex- ually differentiated paths taken in the masochistic fantasy of "A Child Is Being Beaten." She then goes on to describe masochism as a perver- sion that reflects what it undermines: "By projecting a cruel or imperi- ous authority before whom he abases himself, the masochist only acts out in an exaggerated, anthropomorphic, and hence disruptive way the process whereby subjects are culturally spoken." She characterizes the masochist who stages this culturally charged scenario as possessing an