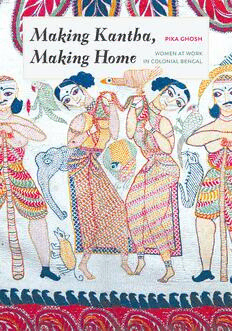

Making Kantha, Making Home: Women at Work in Colonial Bengal PDF

Preview Making Kantha, Making Home: Women at Work in Colonial Bengal

Padma Kaimal K. Sivaramakrishnan Anand A. Yang SerieS editorS GGhhoosshh--tteexxtt--FFIINNAALL..iinndddd 11 55//44//2200 44::0088 PPMM GGhhoosshh--tteexxtt--FFIINNAALL..iinndddd 22 55//44//2200 44::0088 PPMM Making Kantha, Making Home WOMEN AT WORK IN COLONIAL BENGAL PIKA GHOSH UniverSity of WaShington PreSS Seattle GGhhoosshh--tteexxtt--FFIINNAALL..iinndddd 33 55//44//2200 44::0088 PPMM Making Kantha, Making Home was supported by a grant from the McLellan Endowment, established through the generosity of Martha McCleary McLellan and Mary McLellan Williams. Copyright © 2020 by the University of Washington Press Design by Katrina Noble Composed in Minion Pro, typeface designed by Robert Slimbach Photographs are by the author unless otherwise noted. 24 23 22 21 20 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound in Korea All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. UniverSity of WaShington PreSS uwapress.uw.edu Library of CongreSS CataLoging-in-PUbLiCation data Names: Ghosh, Pika, 1969– author. Title: Making kantha, making home : women at work in colonial Bengal / Pika Ghosh. Description: 1st. | Seattle : University of Washington Press, 2020. | Series: Global South Asia | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCn 2019038426 (print) | LCCn 2019038427 (ebook) | iSbn 9780295746999 (hardcover) | iSbn 9780295747002 (ebook) Subjects: LCSh: Kanthas—History. | Kanthas—Themes, motives. | Kanthas—Social aspects. | Art, Bengali. | Art and literature. Classification: LCC nK9276.a1 g46 2020 (print) | LCC nK9276.a1 (ebook) | ddC 746.44—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019038426 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019038427 The paper used in this publication is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, anSi z39.48–1984.∞ GGhhoosshh--tteexxtt--FFIINNAALL..iinndddd 44 55//44//2200 44::0088 PPMM For Ma GGhhoosshh--tteexxtt--FFIINNAALL..iinndddd 55 55//44//2200 44::0088 PPMM ContentS Acknowledgments ix A Note on Transliteration xv INTRODUCTION Kantha, Comfort, and Canon 3 CHAPTER 1 Layers, Thickness, and Resonance: Making Home, Making Whole 53 CHAPTER 2 Manadasundari’s Gift: Worlds in the Household 85 CHAPTER 3 Kamala’s Mandala: A Space of One’s Own 125 CONCLUSION Some Loose Ends 159 Notes 165 Bibliography 211 Index 253 GGhhoosshh--tteexxtt--FFIINNAALL..iinndddd 77 55//44//2200 44::0088 PPMM aCKnoWLedgmentS A book with a long gestation accrues many debts of gratitude, many stories along its journey, and this one is no exception. At the top of my list are Darielle Mason and Les- lie Essoglu of the South Asian Art Department at the Philadelphia Museum of Art for providing the first wonderful opportunity to examine the kantha in the Stella Kram- risch and Jill and Sheldon Bonowitz collections for the 2009 exhibition Kantha: The Embroidered Quilts of Bengal. It was an extraordinarily stimulating experience to work closely with spectacular textiles, and I quickly fell in love with the material. I thank the Costumes and Textile Department for generous access to textiles, files, and ideas. Dilys Blum looked at several textiles with me and offered an invaluable sounding board for ideas. Barbara Darlin facilitated opening up the same textiles and checking object files many times in the past few years. I thank Sara Reiter and Bernice Morris for their conservators’ eye and tools in looking at Kamala’s kantha with me. Tim Tiebout offered his expertise as I struggled with my own photographs of the textiles. Susan Bean not only gave me access to the many objects and images at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, that helped me understand the range of mate- rial I was mulling, but read drafts, offered astute comments at conference panels, and popped images to me via email from her own fieldtrips. Rosemary Crill, Nick Barnard, and Suhasini Sinha at the Victoria and Albert Museum generously accommodated many requests, as did Richard Blurton at the British Museum. Sona Datta and Yuthika Sharma, during their tenure at the British Museum, helped unfold many textiles and scrolls. Shailendra Bhandare at the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology at Oxford University kindly helped me make sense of an embroidered image. At the Yale Center for British Art, during my month-long stint, I received extraordinary research support from Gillian Forester and Elizabeth Fairman, who introduced me to things I had assiduously avoided, urging me to consider sketchbooks and drawings for English samplers, along with narrowing my list of manuscripts with a degree of precision I could not have anticipated. Francis Lapka and Katherine Chabla, along with many others, helped me learn to appreciate the worlds of copies and floating images, their GGhhoosshh--tteexxtt--FFIINNAALL..iinndddd 99 55//44//2200 44::0088 PPMM lines and methods of making. Bindu Gude and Stephen Markel gave me generous access to material at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Sonya Rhie Mace at the Cleveland Museum of Art. At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I thank Melinda Watt, John Guy, and Kurt Behrendt. At the Ratti Textile Center, I thank Giovanna Fiorino-Iannace, Eva DeAngelis-Glasser, Eva Labson, and Isabel Kim, the only textile conservator who shared her technical toys and gave me views into textiles I could not have imagined possible. Her enthusiasm when I spent time in the basement of the Met filled my week with thrilling discoveries and deepened my sense of Indo-Portuguese trade textiles. In Kolkata, Ashis Chakraborty and Bijan Mondal at the Gurusaday Museum at Bratacharigram offered me refuge and quiet to sit with an exceptional collection. I gratefully acknowledge Aroti Dutt, who, in her last years, had opened many invis- ible doors, mostly for her old school friend, my grandmother, as they supported my work with avid interest and passion. Ruby Palchoudhuri and the many designers and embroiderers affiliated with the Crafts Council of West Bengal, including Pritikana Goswami, Bina Dey, and Mahua Lahiri, answered many queries that have greatly enriched my interpretation of stitchwork. Jayanta Sengupta at the Victoria Memorial Hall Museum in Kolkata invariably facilitated many last-minute requests to see and photograph objects. Darshan Shah and Madhurima Chaudhuri were extraordinarily generous in opening up the Weaver’s Studio collection over several visits. Shubhodeep Chanda helped photograph material in several collections with me with much humor, flexibility, and understanding during a hot and wet summer in Kolkata. In Bishnu- pur, Gangadhar and Malati Das opened up their home for this project as they had for earlier ones. In Delhi, I thank Shilpi Goswami at the Alkazi Foundation for her enthusiasm and generosity in sharing access to materials and people. Dr. Joyoti Roy at the National Museum, Dr. Nidhi Harit at the Crafts Museum, Dr. Subhashini Aryan and B. N. Aryan at the K. C. Aryan Collection, and Mr. Chhote Bharany expanded my experience of kantha and generously shared many insights. Romila Thapar offered many questions of the material I was gathering over several cups of tea over the years. I owe an equal debt to Rahul Jain at the Calico Museum in Ahmedabad, Perveen Ahmad at the National Museum, and Dhaka and Teresa Pacheco Pereira at the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon. At the University of North Carolina, two research and study semesters and a leave from the Carolina Women’s Center gave me the time to read and research. A Humani- ties and Fine Arts Award from UNC along with research support from the Philadelphia Museum of Art supported the fieldwork in India in 2007–08. A second award from the University of North Carolina Humanities and Fine Arts Award facilitated the field- work undertaken to review comparative material in the United Kingdom. A Mellon Medieval and Early Modern Studies Research and Travel Grant supported the work in Spain and Portugal in 2011. Research in Bangladesh was funded by fellowships from GGhhoosshh--tteexxtt--FFIINNAALL..iinndddd 1100 55//44//2200 44::0088 PPMM the Social Science Research Council and the American Institute of Bangladesh Studies. My time at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Yale Center for British Art were supported by an American Philosophical Society Franklin grant. Aspects of this material has been presented at Emory University, Jadavpur Univer- sity, Calcutta University, the Birla Academy of Fine Arts in Kolkata, Syracuse University, Middlebury College, the College of Charleston, Washington and Lee University, North Carolina Central University, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the New University of Lisbon, the University of Pennsylvania, the University of California at Berkeley, the Asian Civilization Museum in Singapore, the Courtauld Institute, the annual meetings of the College Art Association, and the Association for Asian Studies. Qamar Adamjee, Molly Aitken, Ian Barrow, Sugata Bose, Rebecca Brown, Dipesh Chakrabarty, Pallabi Chakravorty, Edward Cooke, Paul Courtright, Deepali Dewan, Brian Hatcher, Joyce Flueckiger, Ann Gold, Katherine Hacker, Brian Hatcher, Mary Beth Heston, Sylvia Houghteling, Deborah Hutton, Ananya Jahanara Kabir, Barbara Karl, Melissa Kerin, Scott Kugle, Rochona Majumdar, Walter Melion, Cynthia Packert, Elisabeth Pastan, Leela Prasad, Neeraja Poddar, Sumathi Ramaswamy, Yael Rice, Tamara Sears, Ajay Sinha, Mrinalini Sinha, Christina Smylitopoulos, Ramya Sreenivasan, Sudipa Topdar, and Susan Wadley answered questions, heard and read fragments, and offered valuable insights that have made the book richer than I had imagined at its inception. At the University of North Carolina, Sahar Amer, Glaire Anderson, Bernie Her- man, Amanda Hughes, Wei-Cheng Lin, Susan Harbage Page, Dorothy Verkerk and Lyneise Williams offered valuable suggestions, only some of which I have been able to pursue here. More ineffable but steeped into the fabric of this manuscript is the faith of Jaroslav Folda, Mary Sturgeon, and Darryl Gless. I thank them for believing in me, and in the importance of this study. I have had the pleasure of fruitful dialogues with a generation of students including Saydia Kamal, Klint Ericson, and Tammi Owens. I am grateful to Beth Fischer for her assistance with assembling images for a preliminary version of the manuscript. The generous support of Ken and Naomi Koltun-Fromm, Richard Freedman, Ellen Schulteis, and Elana Wolff, in my brief time at Haverford College, made the completion of the manuscript a pleasurable process. Another genera- tion of students—Emily Chazen and Courtney Carter—helped me stay organized with pictures and citations. The formidable task of obtaining photographs from museum collections was eased by many kind colleagues. For their extraordinary generosity, I thank Siddhartha Shah at the Peabody Essex Museum, Conna Clark and Richard Sieber at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Imogen Laing at the British Museum and Avalon Fotheringham and Jack Glover Gunn at the Victoria and Albert Museum helped me track down material and supplied images. I thank Husna Moudud for permission to use her father’s poetry. Prashanta Bhat, a stalwart throughout my life, prepared the two drawings of kantha embroidery. Michelle Mielke reviewed the index at a critical point. GGhhoosshh--tteexxtt--FFIINNAALL..iinndddd 1111 55//44//2200 44::0088 PPMM At the University of Washington Press, Lorri Hagman shared her quiet strength, patience, and faith, the qualities that I imagine makers of kantha acquired through their work. Caitlin Tyler-Richards supported the interminable and intimidating process of assembling intractable illustrations with much-appreciated kindness and humor. I am deeply grateful for the two readers who responded empathetically and raised issues that needed attention to thickening the layers of these pages. This book would not have been possible without the handful of people who have been there from the beginning. Pallabi Chakraborty’s many thoughtful observations both intensified and alleviated my search for balance in narrative voice and ethical stance, to acknowledge the vibrancy of the accounts, the humanity of the people who shared them, and the complexities of my own subjective position in gaining insights, interpreting, and reframing them. Attuned to the nuances of our shared middle-class Bengali experiences, Pallabi has equally impressed upon my conceptualization of the material over many conversations. Ian Barrow read and re-read the same chapter, offer- ing immensely thoughtful and valuable insights, and Ned Cooke’s astuteness, perhaps best exemplified in bibliographies and images, has immeasurably shaped my think- ing. Padma Kaimal firmly told me to prioritize this project over another half-finished manuscript, and also encouraged me to live and breathe, to value my children, the grief of personal losses, and the solace of walks in the woods even as the book needed to be finished. Rebecca Brown held my hand through the bumpy stretches yet again, as with several earlier projects. I am fortunate to have received some of her gift for intuitively hearing what I wanted to say and suggesting it with the lightest editorial touch. The dogged reassurance from Michael Meister is beyond measure. This project also returns, full circle, to my first days of graduate study under his guidance at the University of Pennsylvania. In hindsight I appreciate the preliminary exploration of domestic imple- ments at the Newark Museum, which, with his enthusiasm and supervision, became the exhibition Cooking for the Gods in 1995. At that time, such domains were becoming worthy of art historical investigation and museum display. The turn to textiles in my current work is therefore a fabrication thickened and layered, recycled with strands of thoughts developing over the decades between these two projects. I cherish the Bengali women, named and unnamed, who opened their doors and lives for this project with infinite warmth, graciousness, and trust. These opportunities would also not have been available without the people who introduced some of them to me, including Anima Nag Chaudhuri, Banasree Nag Chaudhuri, Sagarmoni Sarkar, Papia and Samit Das, Subroto Sardar, Bulbul Basu, Gangadhar Das, Gitanjali Deb, Rajat Deb, Purabi Basu, Nibedita Basu, Chandra Basu, Priyadarshini Basu, and Aditi Basu. Sumita Bhattacharya, who always offered me a home in New York while I worked at the Met, also gave me her children’s kantha. Many Bengalis from my life in Cha- pel Hill contributed with thoughtfulness and kindness over conversations and casual interactions including Sharif Zubaer and Laila Banu, Kaberi Das, Indrani Nandy, and GGhhoosshh--tteexxtt--FFIINNAALL..iinndddd 1122 55//44//2200 44::0088 PPMM