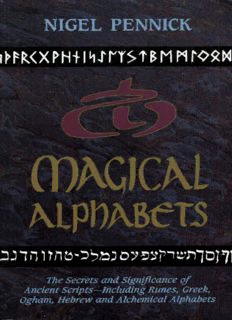

Magical Alphabets: The Secrets and Significance of Ancient Scripts -- Including Runes, Greek, Ogham, Hebrew and Alchemical Alphabets PDF

Preview Magical Alphabets: The Secrets and Significance of Ancient Scripts -- Including Runes, Greek, Ogham, Hebrew and Alchemical Alphabets

NIGEL PENNICK ~WEISERBOOKS l!J Boston, MA/York Beach, ME First American edition published in 1992 by Red Wheel/Weiser, 1.1.(' York Beach, ME With offices at 368 Congress Street Boston, MA 02210 www.redwhee/weiser.colll 07 06 05 04 03 14 13 12 II 10 Copyright © 1992 Nigel Pennick All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans mitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical. including pho tocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Red Wheel/Weiser. Reviewers may quote brief passages. This work was first published in England by Rider Books, a division of Random House U.K. Limited, London, under the title The Seerel Lor!' of Runes lind mha Ancielll Alp/wbels. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pennick, Nigel. Magical <Jlphabets / Nigel Pennick, p. cm, Includes bibliographical references, J. Magic, 2, Alphabets-Miscellanea, I. Title, BFI623.A45P46 1992 I 33.4'3-dc20 92-7859 CIP ISBN 0-87728-747-3 BJ All illustrations in this book were made by the author, except for Ilumbcrs (" 7, 10, 15,24,25,36, 43, 55,56,57,61-63, which arc historic illustratiolls from the author's picture collection, Printed in the United States of America The paper used in the publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printer Library Materials Z39.4K-19K4. Contents Introduction 1 1 The Hebrew Alphabet 7 Qabalistic speculations 8 The meaning of Hebrew letters 13 Qabalistic letter manipulations 21 Hebrew magic squares and grids 31 Hebrew letter squares and other amulets 38 Medieval Hebrew-derived alphabets 39 2 The Greek Alphabet 43 Greek alphabet traditions 57 Greek gematria 60 Christian Greek gematria 64 The Etruscan script 73 3 The Runes 74 The Gothic alphabet 111 Runes and trees 116 4 The Celtic Oghams and Bardic Alphabet 123 Cryptic Oghams and other variant forms 148 The Bardic alphabets 154 The Gaelic alphabet 166 Variations in Northern European alphabets 168 5 Magical and Alchemical Alphabets 171 The Vehmgericht, the Inquisition and the alphabet of Westphalia 177 House, holdings and stonemason's marks 182 Magic grid ciphers 186 Magical uses of the Roman alphabet 188 6 Magic Squares, Literary Labyrinths and Modern Uses 203 The magic square and the word labyrinth 203 Ramon L1ull, magic squares and the Talismanic art 212 Esoteric alphabets in the modern and post-modern era 216 Postscript 223 Appendices I The Meaning of Hebrew Letters 229 II Greek Letter Meanings 230 III The Runic Correspondences 231 IV Runes and Tarot Major Arcana 233 V Ogham Correspondences 234 VI Gaelic Alphabet Correspondences 235 VII Magic Square Correspondences 236 VIII The 72 Names of God 237 Glossary 239 Bibliography 241 I call strong Pan. the substance of the whole, Etherial. marine. earthly. general soul. Undying fire; for all the world is thine, And all are parts of thee, 0 pow'r divine ... All parts of matter. various form'd, obey, All Nature's change thro' thy protecting care. And all mankind thy lib'ral bounties share, For these where'er dispersed thro' boundless space, Still find thy providence support their race. The Orphic Hymn to Pan Fig. 1. Letter-trees: the Hebrew name of God. the Buddhist mantra Hum. and the Northern Tradition tree bind-rune. Introduction A symbol is ever, to him who has eyes for it, some dimmer or clearer revelation of the God-like. HELENA BLAVATSKY At a first, cursory glance, the subject of alphabets, secret or otherwise, may not appear to tell us much about the world and ourselves. But another, longer, look will show anyone of this opinion that he or she is wrong. Alphabets are one of the most highly sophisticated means by which we humans can try to gain some understanding of the world, and our place within it. When constructed properly, as all ancient ones are, each alphabet is metaphorical in nature. Language itself is a metaphor, for it represents objects and concepts whilst it is not those objects and concepts themselves. The very basis of language is metaphorical. We usually distinguish things by comparison; our basic description of the world around us is full of examples. When we ask, 'What is it?', we tend to reply by making a comparison: we say it is like another thing which resembles it in some way, real or imagined. Within the described thing, object or quality, we seek some character by which it can be fitted into some human conceptual framework. We can see this process in action with reference to the human body. We speak of a body of water, a body of work, even a body of men. We speak of the head of a bed, a table, a page, a nail, a stream of water, a household or an organization. A clock has a face, just as does a playing card, a rock and a piece of planed wood. A hill has a brow, a cup possesses a lip, as does a crater; combs and gear-wheels have teeth, and a page has a foot. Weapons are called arms. A race or a contest may be divided into a number of legs. A shoe may have a tongue, as does a certain type of carpentry joint, and 1