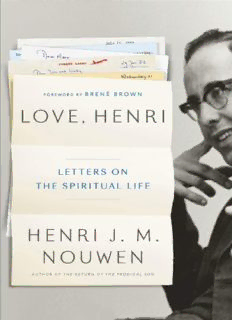

Love, Henri: Letters on the Spiritual Life PDF

Preview Love, Henri: Letters on the Spiritual Life

Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Preface Foreword A Note from the Editor Part I Part II Part III Epilogue Acknowledgments FOR SUE MOSTELLER When Henri Nouwen died in 1996, he left us thirty-nine books and hundreds of articles on the spiritual life and what he called his “adventures with God.”*1 He also bequeathed a treasury of personal papers. The largest part of the cache was correspondence. Over his lifetime Henri received more than 16,000 letters. He kept every postcard, piece of paper, fax and greeting card that arrived in his mail. And he responded to each of them. Managing his correspondence was an integral part of his working day. The sheer volume of mail made it necessary to employ an administrative assistant to sort, preread, and highlight what needed an immediate response. Henri would then read them himself and reply into a Dictaphone for transcription. Letters to close friends were usually handwritten, often on postcards from his large collection of art cards. His penmanship was neat and flowing. He never wrote drafts and rarely made corrections. Shortly after I started as Henri’s archivist in the summer of 2000, I was taken to the attic of a house at L’Arche Daybreak, the community near Toronto where Henri had made his last home. After climbing a steep staircase into an overheated attic, I confronted a dozen or more filing cabinets—tall, short, in a variety of colors—lined up in the middle of the room. Along the walls and in every corner were stacks of boxes. All were filled with letters. For the next fifteen years, I identified, numbered and catalogued each page in this remarkable collection. It was a daunting task, but one that evolved into a labor of love. The letters now form part of the Henri J. M. Nouwen Archives and Research Collection at the University of St. Michael’s College, University of Toronto. Housed in their new acid-free folders and boxes, they extend to sixty- five linear feet! It has been slow work, but the time has come to share them. This first volume is being released to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of Henri’s death in 1996. It celebrates his lasting legacy both to original readers and to a new generation of spiritual seekers. It is a testament to his deep need to connect with others, knowing that in any genuine encounter we are reaching out to the Divine. Though some of the letters are drawn from his personal archive, most come from the original recipients. In the twenty years since his death, over three thousand letters have been collected from the homes, offices, basements and attics of his correspondents. Although the letters began as an intimate exchange between two people, their power today speaks to Henri’s belief that what is most personal—our brokenness, our insecurities, our jagged edges—is most universal. For Henri, letter writing was an integral part of friendship. In 1996, just months before his death, he recorded in his journal: This afternoon I wrote many postcards. While writing I experienced a deep love for all the friends I was writing to. My heart was full of gratitude and affection, and I wish I could embrace each of my friends and let them know how much they mean to me and how much I miss them.*2 He attached great importance to words to reach out across solitudes of experience. “I can’t tell you how healing and consoling your gentle and loving words are to me,” he wrote to his friend Jim.*3 Words, he felt, had the power to give life and when offered in friendship could be a source of grace. “Your letter is a real oasis in my desert,” he confided.*4 Henri wrote generous and intimate letters. In response to people seeking his advice he never condemned or judged but instead used stories from his own experience to inspire or teach. At the same time, he could be challenging, even demanding. He called his readers to be faithful to choices they had made and to practice the spiritual disciplines of prayer, community and solidarity with the poor. He cautioned against the temptations that pulled people off the “narrow path” and emphasized the importance of making choices that took the needs of others into account. He had a gift for deep listening. After reading a pain-filled letter, he identified the struggle with precision and responded with compassion. “You have been heard. You are loved. You are not alone” was the implicit message. After receiving a letter from Henri on how to care for her dying mother, a woman wrote back: I am so grateful to you for helping me to find and make meaning of my journey on earth….My heart is bursting with gratitude for the comfort you have provided me during my mother’s illness and death last month….You gave me insight and courage to stay with the pain and wait with her for God. I feel transformed by my experience and I want to thank you for helping me to endure her suffering, and therefore be with her, really be with her….So you see why I feel such community with you? You have helped me to hope in and not wish for, and I feel I have really learned to be present in the lives of my mother and father, from who I first learned about God.*5 Henri created a safe place for vulnerabilities because he was honest with his own. “You probably realize,” he wrote to a woman struggling with a chronic illness, “that I have no answers for all your questions, but I receive your questions more as an invitation for a relationship between two searching Christians than as a request to be taught.”*6 As I considered what letters to include in this volume, my guiding question was: What do people need to hear right now? The times we live in have changed —there are now email and text messages—fleeting forms of communication; few people put pen to paper anymore—but our human challenges remain the same: loss, sickness, injustice, finding and losing love, discerning a career path, handling conflict, managing our emotions and coping with self-doubt. Yet Henri believed that it is precisely in those struggles that we ultimately find God. It is in the big questions—who is God, and what is the meaning of our life?—that we are drawn to know ourselves better. Henri’s responses to readers are powerful because he drew from his own lived experience. He wrote to a friend: Jesus’ invitation to “lay down my life for others” has always meant more to me than physical martyrdom. I have always heard these words as an invitation to make my own life struggles, my doubt, my hopes, my fear and my joys, my pains and my moments of ecstasy available to others as source of consolation and healing. To witness for Christ means to me to witness for Him what I have seen with my own eyes, heard with my own ears and touched with my own hands.*7 Whereas others hid their vulnerabilities and weakness, Henri drew on them to form a community of solidarity with his friends and readers. The letters in this volume trace twenty-two years in Henri’s life journey— from his time as a teacher to an interlude as a visiting Trappist monk to his time as a Latin American missionary and finally to pastor of a community with people with disabilities. We see that in spite of outward success and popularity, he suffered from what he called “his demons”—loneliness, restlessness, falls into depression and feelings of rejection. Yet it is how he lived those lifelong struggles that makes him an inspiring guide for our own lives. He lived with courage and self-awareness, gradually learning to befriend his pain and ultimately being redeemed by it. He knew that the only way out of suffering is through it. Where did his “demons” come from? His early life was filled with opportunity and privilege. Even the German wartime occupation of Holland left his family relatively unscathed. He received his academic education—in theology, philosophy and psychology—from some of the most eminent teachers in his home country and the United States. He had a curious mind and an artist’s eye. What troubled him was an inner contradiction on how he was meant to live his life. As a young man he heard two voices in his head: One voice said, “Henri, be sure you make it on your own, be sure you can do it yourself, be sure you become an independent person. Be sure that I can be proud of you.” And another voice said, “Henri, whatever you are going to do, even if you don’t do anything very interesting in the eyes of the world, be sure you stay close to the heart of Jesus, be sure you stay close to the love of God.”*8 He was torn between the two imperatives of upward and downward mobility. As a Catholic, he experienced it as a struggle between the priorities of his earthly father and his heavenly father. Could he please both? Did he deserve to be loved? His feelings of inadequacy were exacerbated by an unusual degree of emotional sensitivity that left him with little insulation from the abrasions of life. A close friend, Sue Mosteller, CSJ, observed: He is truly a man whose heart is so open and so vulnerable, so receptive and so giving that our own little hearts feel solidarity and safety when he speaks to us and calls us to grow in like manner. It is the authenticity of his own heart which we recognize, identify with, and hope to imitate.*9 He also struggled with intimacy and conflicting feelings about his sexuality. The vocation of celibate priest exacted a heavy price. His desire for a “unique friendship”*10 conflicted with his vow to give his heart only to Jesus. He never publicly acknowledged his homosexuality, deciding that coming out in public would eclipse his larger mission of connecting people with God.*11 Nor did he leave the Church, as many of his generation of Catholic clergy did. His letters document the painful effort to live out this choice. Toward the end of his life he wrote: My sexuality will remain a great source of suffering to me until I die. I don’t think there is any “solution.” The pain is truly “mine” and I have to own it. Any “relational solution” will be a disaster. I feel deeply called by God to live my vows well even when it means a lot of pain. But I trust that the pain will be fruitful.*12 He never entirely transcended his struggles. In spite of his insights into solitude and silence, busyness dogged him throughout his life. Though often fatigued, he rarely took proper care of himself. For all his ability to listen deeply to people in crisis, he could be impatient with those around him. His longing for human affection and frequent slides into self-rejection made him a needy and demanding friend. However, by the end of his life, he had grown to accept his “unresolvable struggle”:*13 I know that I do not need to be ashamed of my needs, that my demons are not really demons but angels in disguise, allowing me to love generously, to be faithful to my friends, to be sensitive to the many forms of human suffering and to live my priesthood with courage and confidence.*14 In his final years, his letters became shorter and lighter. We sense his increasing capacity for “childlike” wonder. To a friend struggling with aging, he wrote: Personally I believe that being an elder can be a real grace. After having seen so much of life and having “made it” in so many ways there is still that possibility of growing into a second childhood, a second naiveté. I think that is quite an exciting possibility and I pray that God will allow you to be reborn in such a new way of being.*15 Each letter in this volume tells a story. Together they serve as an inspiration that peace and inner freedom are attainable. Henri saw our struggles not as “problems” to be overcome but as gateways through which we can learn generosity and tenderness. By living our struggles well, we move beyond a life of constriction to a life that is expansive and generative. Our goal, Henri felt, is to move from the house of fear to the house of love: Hardly a day passes in our lives without our experience of inner and outer fear, anxieties, apprehensions and preoccupations. These dark powers have pervaded every part of our world to such a degree that we can never fully escape them. Still it is possible not to belong to these powers, not to build our dwelling place among them, but to choose the house of love as our home. This choice is made not just once and for all but by living a spiritual life, praying at all times and thus breathing God’s breath. Through the spiritual life we gradually move from the house of fear to the house of love.*16 As a trained psychologist in the complexities of the human psyche, Henri unmasks our hidden motives. As a pastor, he calls us to reach for a higher level that acknowledges the spiritual dimension of life. As a fellow pilgrim, he honors our flawed lives and allows space for our failures and bad choices. His letters have transformed the way I live my own struggles. My hope is that they will do the same for you.

Description: