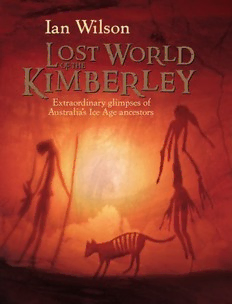

Lost world of the Kimberley: extraordinary glimpses of Australia's Ice Age ancestors PDF

Preview Lost world of the Kimberley: extraordinary glimpses of Australia's Ice Age ancestors

LOSTWORLD 22/8/05 4:04 PM Page 1 Australia’s Kimberley was the cultural hub of the Ice Age world. Today it holds within its bounds the world’s largest collection of Ice Age figurative art, giving us vital clues to the origins of other cultures and civilisations right across the world. Back at a time when most of Europe lay deep beneath ice sheets,a people in the remote and rugged Kimberly Ranges of north-west Australia created figurative paintings of such verve and talent that they surpass all other ofthe world’s rock art. Known as ‘Bradshaws’,after pioneer farmer Joseph Bradshaw who chanced upon the first examples in 1891, the Kimberley paintings feature lithe,graceful human figures depicted in a fashion altogether different from that of even the oldest traditional art, providing extraordinary visual insights into the everyday lives ofIce Age people. So who were these Bradshaw people? When did they live? What happened to them? Ian Wilson describes the early research on the Bradshaw paintings, and explains how advanced dating techniques have shed new light on the findings. He explores the theories put forward on the origins of these seafaring people; one possibility is that they arrived from the Andaman Islands,where pygmy-like tribes still survive.Farther afield still,the author draws connections with Saharan peoples,and he even unearths startling similarities with South American tribes. Lost World ofthe Kimberleyis a wide-ranging and provocative look at the very Australian,yet also potentially international,mystery ofthe Bradshaw paintings ofthe Kimberley—one ofAustralia’s least known, yet most extraordinary,national treasures. A L L E N & U N W I N www.allenandunwin.com Cover design: Zoë Sadokierski AU S T R A L I A N H I S T O RY Lost World 1-4 12/1/06 4:17 PM Page i Lost World 1-4 12/1/06 4:17 PM Page ii IAN WILSON has been a professional author since 1979 and has published more than twenty books, including The Turin Shroud, Jesus: The Evidence, and The Blood and the Shroud. He emigrated to Australia in 1995 and lives in Brisbane. L o s t W o r l d 1 - 4 1 2 / 1 / 0 6 4 : 1 7 P M P a g e i i i Lost World 1-4 12/1/06 4:17 PM Page iv First published in 2006 Copyright © Ian Wilson 2006 All rights reserved. No part ofthis book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. TheAustralian Copyright Act 1968(the Act) allows a maximum ofone chapter or 10 per cent ofthis book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. Allen & Unwin 83 Alexander Street Crows Nest NSW 2065 Australia Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100 Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com National Library ofAustralia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Wilson, Ian, 1941- . Lost world ofthe Kimberley. Bibliography. Includes index. ISBN 1 74114 391 8. 1. Rock paintings - Western Australia - Kimberley. 2. Aboriginal Australians - Western Australia - Kimberley - History. 3. Kimberley (W.A.) - Antiquities. I. Title. 759.0113099414 Set in 12/15 pt Bell MT Regular by Midland Typesetters, Victoria Printed by South Wind Production, Singapore 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Lost World 1-4 12/1/06 4:17 PM Page v CONTENTS Author’s preface vii Chapter 1 Drop-in at Reindeer Rock 1 Chapter 2 Early rock art encounters 10 Chapter 3 Modern-day encounters 28 Chapter 4 Twenty-nine in a boat 45 Chapter 5 Hands of time 55 Chapter 6 ‘Mother’ and her ‘dogs’ 66 Chapter 7 ‘Breadbaskets’ and puppets 84 Chapter 8 Boat design pioneers 102 Chapter 9 Time of the spears 115 Chapter 10 Odes to the boomerang 135 Chapter 11 A Bradshaw ‘Lost City’? 148 Chapter 12 Follow that river 171 Chapter 13 Putting people to the paintings 186 Chapter 14 Putting dates to the paintings 205 Chapter 15 Putting genes to the paintings 221 Chapter 16 Tracing where they went 241 Chapter 17 Window on the world’s oldest culture 257 Picture credits 279 Notes 281 Bibliography 299 Index 308 Lost World 1-4 12/1/06 4:17 PM Page vi Lost World 1-4 12/1/06 4:17 PM Page vii AUTHOR’S PREFACE In 1994 my wife Judith and I visited Australia for the first time at the invitation of the Sydney Writers’ Festival. In the course of a brief but unforgettable tour we so fell in love with the country and its lifestyle that we applied to emigrate, and after due process moved house from Bristol, England to a pleasant suburb of Brisbane, Australia. It was a decision that many of our friends and acquaintances greeted with near disbelief. ‘But you’re a historian!’ they exclaimed. ‘What on earth are you doing going to a country that has no history?’ Now, ten years on, perhaps this book will help set to rights some of those all-too-prevalent misconceptions. This said, the extremely ancient, enigmatic and so talented paintings that form my subject are not of the stuff immediately to be put on every future tourist itinerary. Even by Australian standards the still scant-explored Kimberley region where the paintings are located is remote, vast, and almost completely lacking in any of the normal tourist amenities. And as anyone who manages the trip quickly appreciates, that is the way it also needs to stay. But these paintings exist in literally tens of thousands across an area almost the size of Spain. And an awareness and even partial understanding of them is arguably fundamental to our understanding of the whole history of humankind in its Ice Age infancy. Unless there is some fatal flaw to the dating of these paintings, back at a time when most of Europe lay deep beneath ice sheets a people in Australia were creating elaborate garments for themselves, building ocean-going boats, cultivating root crops and enjoying a rich ceremonial life. Not least, they were creating figurative paintings of verve and talent that surpasses all other of the world’s rock art, and would not be seen again until the rise of the ancient Egyptian and Near Eastern civilisations. Though in tackling this subject I have strayed into the field of the prehistorian, rather than the historian, in this particular instance I make no apology. The paintings in question are so full of details of the remote era from which they derive that they actually represent a far more vital and vivid documentary source than could any dry or dusty chronicle. Lost World 1-4 12/1/06 4:17 PM Page viii LOST WORLD OF THE KIMBERLEY Two most redoubtable women qualify as equal first among the individ- uals to whom this book is indebted. My wife Judith has been at my side through 38 years of marriage and 28 years of my book writing, but this par- ticular book has undoubtedly demanded more from her than anything previously. Hanging out of helicopters and crawling beneath narrow rock overhangs to photograph paintings in wild terrain is not for the faint- hearted. But Judith coped magnificently to create the great majority of photographs reproduced in this book, as well as making interpretative drawings, checking the text, and innumerable other chores. No less invalu- able has been the help of archaeologist Lee Scott-Virtue of Kimberley Specialists, Kununurra. Most cheerfully and capably she took on the tasks of being our expedition leader, guide, cook, bush lore specialist and driver throughout the full-scale four-wheel drive expedition that was demanded by our need to view the remotely located paintings at first hand. She has similarly been a tower of support and strength throughout. Amongst others to whom I am indebted are Joc Schmiechen for checking the book manuscript, directing me to important sources that I had missed, and very freely volunteering his wealth of first-hand knowledge and photographs; Russell Willis of Willis’s Walkabouts for generously allowing use of his photographs and data in Chapter 12; John Bradshaw for supplying the photograph of his great-uncle Joseph Bradshaw, and for checking the chapter describing Bradshaw’s discovery; Adrian Parker for supplying the photograph of the panel discovered by Bradshaw; Slingair helicopter pilot Tim Anders for introducing us to the previously undocumented rock painting sites of Reindeer Rock and Wullumara Creek; Bruce and Robyn Ellison of the Faraway Bay Bush Camp for making it possible for us to access hitherto undocumented rock art sites on the Kimberley’s north-west coast; Steve McIntosh of Faraway Bay for guiding us to these sites; and Pawel Valde-Nowak of the Institute of Archaeology, Kraków, Poland, for providing difficult-to-obtain data on Poland’s unique Ice Age boomerang. My warmest thanks, also, to the following people for innumerable other crucial points of assistance: sculptor John Robinson of Yeovil, Somerset, England; Len Zell, author of the excellent Guide to the Kimberley Coast; Ian Levy; Christopher Chippindale; John Taylor of Tasmania; John Presser of Tasmania; David viii Lost World 1-4 12/1/06 4:17 PM Page ix AUTHOR’S PREFACE Owen, author of Thylacine; Dr Stephen Wroe of the University of Sydney; Tim McIntyre of the University of Queensland; Dr Michael D. Coe of Yale University; Jean-Michel Chazine of the University of Marseille; Dr John Prag from Manchester Museum; Dr Robert Paddle of the Australian Catholic University; Dr Lawrence Blair; Dean Goodgame; Barrie Schwortz; Ju Ju ‘Burriwee’ Wilson; photographer Peter Eve; Aboriginal artist Warren Djorlom; Helen Bunning; Grahame Walsh; Nadia Donnelly of Kununurra Visitor Centre; Sheryl Backhouse; Barry Hart; James Sokoll; Ian Thomson; Vrony Kern; Ian Holmes; Philip Courtenay of ADFAS; Adriennne Alexander; Natasha Pearson of Lord’s Kakadu and Arnhemland Safaris; Conrad Stacey; Jean-Claude Bragard; Petra Collier; Brisbane City Library (in particular the ever-helpful staff of our local mobile library); University of Queensland Library; the Mitchell Library, Sydney. And not least among all these, Patrick Gallagher, Managing Director of Allen & Unwin, Sydney, for giving the project the vital push-start ofa book commission, and for being so patient and understanding during its long gestation. Authors can make all kinds of gaffes and mistakes in putting together a book manuscript, and this author is certainly no exception. A good publisher provides a suitably literate and eagle-eyed copy editor to spot these errors. In fulfilling this all too often unsung task, Karen Ward has not only been one of the very best whom I have come across, she has also made a number of helpful constructive suggestions. I am deeply grateful to Karen and to Allen & Unwin editor Jeanmarie Morosin for all their care and their patience steering this book towards publication. In the case of my attempted interpretations of the Bradshaw paintings, whatever errors these may contain will be entirely from my own shortcom- ings, and I will welcome all suggested corrections to these. The intention of this book is not in any way to provide some sort ofdefinitive authority on the subject. Rather, it is to open it up to the widest possible, intelligent debate. Ian Wilson Moggill, Queensland July 2005 ix