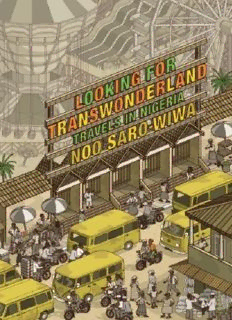

Looking for Transwonderland: Travels in Nigeria PDF

Preview Looking for Transwonderland: Travels in Nigeria

Table of Contents Title Page Dedication Prologue Chapter 1 - Centre of Excellence Chapter 2 - Oil and People on Water Chapter 3 - Total Formula for Victory Over the Hardships of Life Chapter 4 - Under the Light of Fading Stars Chapter 5 - Transwonderland Chapter 6 - In the Chop House Chapter 7 - Spiderman, Rock Stars and Gigolos Chapter 8 - Straddling Modernity’s Kofar Chapter 9 - Where Are Those Stupid Animals? Chapter 10 - Hidden Legacies Chapter 11 - Kingdom of Heaven Chapter 12 - Masquerade Mischief Chapter 13 - Spoiling Nature’s Spoils Chapter 14 - Behind the Mask Chapter 15 - Tending the Backyard Chapter 16 - Truth and Reconciliation Epilogue Acknowledgments Sources Copyright Page In loving memory of Sara Al-Bader (1976 – 2010), my dear friend and inspiration. You’ll never be forgotten. Prologue The deep voices boomed loudly enough to jolt me from my mid- morning snooze. My eyes opened up to a predominantly male crowd of Nigerians clustered near the information desk in the centre of Gatwick Airport’s departure lounge, gesticulating angrily. ‘You are treating us like animals!’ one man barked at the blond airport official, who absorbed the verbal barrage with a passive, slightly bemused smirk. ‘Are we not human beings, like you?’ A mechanical fault had delayed our flight to Lagos indefinitely, and some of the Nigerian passengers – always alive to the whiff of conspiracy – smelt something fishy. They gathered in a circle around a fellow passenger who had appointed himself as spokesman for their suspicions. Angling his head towards the mezzanine, this oga sermonised at maximum volume about Gatwick’s strategy to humiliate us, and Virgin’s stinginess in not providing a replacement aircraft. Others waved their compensatory food vouchers at the information desk staff, shouting at point-blank range about Gatwick’s deliberate withholding of information. They huffed and pontificated, everyone offering a theory on why the plane was grounded, gradually transforming the tranquillity of the departure lounge into the tumult of an angry football terrace. But whoever decided to send in armed police to monitor the situation was taking an unnecessary precaution. I wanted to tell them not to panic: Nigerians like to shout at the tops of our voices, whether we’re telling a joke, praying in church or rocking a baby to sleep. I also wanted to tell them that we’re not crazy – decades of political corruption have made us deeply suspicious of authority – but there was no one to discuss this with, so I had no choice but to sit and watch our national image sink further in the eyes of the world. When two Italian men walked past, one of them giggled to his friend, tapped his forehead and said the word ‘mentale’ before swinging round to take one last derisive glance at the spectacle. The English travellers, more understated in their feelings, shrugged their shoulders at one another and smiled with their eyes, while two spiky-haired employees at a nearby electronics shop chatted amongst themselves and gestured their condemnation of the crowd’s behaviour. An hour later, the airport information officer switched on the tannoy to inform the Nigerian passengers of a 50 per cent discount on our next return flight. ‘We apologise for the delay,’ the woman began, but her words were drowned out by the disgruntled crowd, which was now clamouring for extra food vouchers. She tried again, this time half bellowing down the microphone. ‘Can you please be quiet, I’m trying to help you!’ The entire departure lounge flinched in surprise. ‘We lack discipline,’ an older Nigerian lady murmured to me as she shook her head in shame. She and I, along with the silent majority of Lagos-bound passengers, watched from one side, not sure whether to laugh or cry. Being Nigerian can be the most embarrassing of burdens. We’re constantly wincing at the sight of some of our compatriots, who have committed themselves to presenting us as a nation of ruffians. Their efforts are richly rewarded at airports, where the very nature of such venues ensures that our rowdy reputation enjoys an extensive, global reach. I’ve always dreaded airports for that reason. They are also places where, as a Nigerian raised in England, I’m forced to watch the European and African mindsets collide in a way that equally splits my loyalty and disdain towards both: I wanted to spank that Italian for misunderstanding our behaviour and revelling in his sense of superiority; I also cringed at the noisy Nigerian passengers for their paranoia, ill discipline and obliviousness to British cultural norms. But the embarrassment and sense of cultural dislocation were nothing new. These airport fiascos began for me back in 1983, when a similar scenario saw my family and 300 irate Nigeria Airways passengers bussed like low-grade cattle to a faraway hotel in Brighton until our delayed flight was ready. I was too young to understand the circumstances surrounding the delay, yet I remember the shouting, chaos and feelings of national shame with visceral clarity. From that day onwards, travelling from England to Nigeria became a source of anxiety for me, a journey I repeated only under duress. As a teenager, I virtually had to be escorted by the ankles onto a Nigeria Airways flight at the start of the summer holidays, not only because I wanted to avoid all that airport angst, but also because I didn’t want to reach the ultimate destination. Having to spend those two months in my unglamorous, godforsaken motherland with its penchant for noise and disorder felt like a punishment. I wanted a real holiday, riding banana boats in Barbados or eating pizzas by the Spanish Steps, like my school friends. But my parents didn’t have the money or the inclination for that sort of thing. ‘We’re going home,’ they insisted with the firmness of people who knew better than to waste exotic travel on the very young. Come July each year, I would pack my bags and prepare to serve my annual sentence in a country where the only ‘development’ I witnessed was the advance of new wall cracks and cobwebs, and where ‘growth’ simply meant larger damp stains on the ceiling. Nothing ever seemed to change for the better politically or economically in 1980s Nigeria. I would arrive at an airport that hadn’t been refurbished in twenty years. The humid viscous air, pointlessly stirred by sleepy ceiling fans, would smother me like a pillow and gave a foretaste of the decrepitude and discomfort that lay ahead. Back then, when international flying was considered the height of sophistication, many of the child passengers were dressed as if attending a black-tie event. Parents tarted up their little girls in frilly party dresses; the boys sweated it out in bow ties and dinner jackets; while armed thieves (otherwise known as government soldiers) rummaged through everyone’s luggage at customs. Only in Nigeria could you see machine guns, tuxedos, army fatigues and evening frocks together at an airport. The insane aesthetic summarised my country’s vanities and bathos

Description: