Life beside itself : imagining care in the Canadian Arctic PDF

Preview Life beside itself : imagining care in the Canadian Arctic

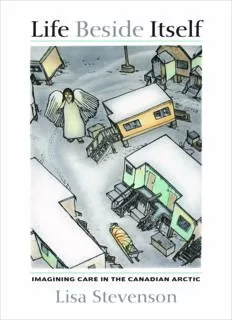

Life Beside Itself Imagining Care in the Canadian Arctic Lisa Stevenson university of california press Life Beside Itself Life Beside Itself Imagining Care in the Canadian Arctic Lisa Stevenson university of california press University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2014 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stevenson, Lisa. Life beside itself : imagining care in the Canadian Arctic / Lisa Stevenson. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-520-28260-5 (Cloth : alk. paper) — isbn 978-0-520-28294-0 (Paper : alk. paper) — isbn 978-0-520-95855-5 (e-book) 1. Inuit—Medical care—Canada—History. 2. Tuber- culosis—Canada—History. 3. Inuit—Health and hygiene—Canada—History. I. Title. rc314.s74 2014 362.19699'5008997124—dc23 2014006556 Manufactured in the United States of America 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 In keeping with a commitment to support environmentally responsible and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on Natures Natural, a fi ber that contains 30% post-consumer waste and meets the minimum requirements of ansi/niso z39.48–1992 (r 1997) (Permanence of Paper). Contents Prologue: Between Two Women vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1. Facts and Images 21 2. Cooperating 49 3. Anonymous Care 75 4. Life-of-the-Name 103 5. Why Two Clocks? 129 6. Song 149 Epilogue: Writing on Styrofoam 171 Notes 175 References 217 List of Illustrations 243 Index 245 Prologue Between Two Women A voice involves the throat, saliva, infancy, the patina of experienced life, the mind’s intentions, the pleasure of giving a personal form to sound waves. What attracts you is the pleasure this voice puts into existing. Italo Calvino, A King Listens In the midst of a Thanksgiving dinner, with people splayed out on the fl oor—a middle-aged man with his back against the legs of a chair recounting a road trip across the southern United States, a teenager twisting her hair around her fi nger and gazing inertly in front of her, a couple of kids lying on their stomachs, engrossed in their own densely laid world of right and wrong—and everyone eating and talking and bickering as most families, happy or sad, eat and talk and bicker, in the midst of all that, two women face each other. The younger one is kneel- ing on the fl oor at the feet of the old woman, a woman whose legs can no longer support her weight, a woman who has been lifted from a car into the house and placed on the living room couch. The two women bring their faces close together—so close they are almost touching, their arms resting on each other’s shoulders. They sway slightly as they begin to kataq. The younger woman starts, and the sounds she makes come from the back of her throat, low and thick, almost growling. Ham ma ham ma, ham ma, ham ma—she breathes in and out in a steady rhythm, intensely, her vocal cords bruising each other. Buzzing, panting, the older woman’s voice comes in and moves up and down as if plucking the lower rhythm, teasing it almost. The sounds and rhythms pass from body to body, echoing and playing with each other, growling, vii viii | Prologue buzzing, yelping. There’s something machine-like and modern about the sounds, which are also archaic and guttural. Ham me, ham ma, ma, ham ma, ham ma, ham ma Ha ha ha, ha he he, ha he he, ha he he ha ha ha ha Then the old lady breaks off and cackles loudly, hooting almost. The younger woman laughs too and wipes away tears. People smile, clap, and go back to what they were doing. A few months later the old lady dies in her sleep. I am in the house when the young woman returns, but I’ve already heard the news. I hear her shutting the door, putting down her purse. The ordinariness of the sounds is hard. “She’s gone,” the young woman tells me, thinking I don’t know. “My anaana is gone.” In my memory it’s as if she is swaying, but not rhythmically, rather as if she might fall over.

Description: