Knight: The Warrior and World of Chivalry PDF

Preview Knight: The Warrior and World of Chivalry

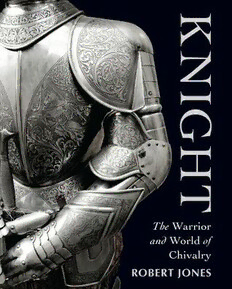

The Warrior and World of Chivalry ROBERT JONES K N I G HT OSPREY PUBLISHING iCS. K N I G HT The Warrior and World of Chivalry ROBERT JONES First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Osprey Publishing, Midland House, West Way, Botley, Oxford, OX2 OPH, UK 44-02 23rd Street, Suite 219, Long Island City, NY 11101, USA E-mail: [email protected] OSPREY PUBLISHING IS PART OF THE OSPREY GROUP © 2011 Robert Jones All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Enquiries should be addressed to the Publishers. Everv attempt has been made by the Publisher to secure the appropriate permissions for material reproduced in this book. If there has been any oversight we will be happy to rectify the situation and written submission should be made to the Publishers. Robert Jones has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Print ISBN 978 1 84908 312 6 Cover and page design by: Myriam Bell Design, France Index by Mark Parkin Typeset in Cochin Originated by PDQ Digital Media Solutions, Suffolk, UK Printed in China through Worldprint 11 12 13 14 15 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Osprey Publishing is supporting the Woodland Trust, the UK's leading woodland conservation charity, by funding the dedication of trees. www.ospreypublishing.com Front cover: Spanish armour from Toledo, (istock images) Chapter openers: pp.6-7Armour for field and tournament of King Henry VIII, dated 1540 (© Board of Trustees of the Armouries, 11.8). pp.28-29 Foot combat armour, English, Southwark, 1520 (© Board of Trustees of the Armouries, 11.6). pp.66—67 (istock images), pp.94-95 Armour for the field and tilt. South German, probably Augsburg, about 1550-60 (© Board of Trustees of the Armouries, 11.87). pp.142—143 Field and tournament armour of Friedrich Wilhelm I, Duke of Saxe-Altenburg. German, Augsburg, t'.1590 (© Board ol Trustees of the Armouries, 11.359). pp.178—179 Tonlet armour. English, Southwark, 1520. (© Board of Trustees of the Armouries, 11.7). pp.210—211 Jousting armour. (Bridgeman Art Libraiy) CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 6 CHAPTER ONE: ARMS AND ARMOUR 28 CHAPTER TWO: TACTICS AND TRAINING 66 CHAPTER THREE: CAMPAIGN AND BATTLE 94 CHAPTER FOUR: CHIVALRY 142 CHAPTER FIVE: BEYOND THE BATTLEFIELD 178 CHAPTER SIX: THE DEATH OF KNIGHTHOOD? 210 GLOSSARY 224 BIBLIOGRAPHY 227 INDEX 235 j T HERE CAN BE NO WARRIOR QUITE SO ICONIC AND IMMEDIATELY recognizable as the medieval knight. More than any other he remains a part ol contemporary culture. Not only does he ride his charger, resplendent in his shining armour and colourful heraldry, through novels and movies, but his armour still decorates museums, castles and stately homes, and his image in brass or stone adorns our churches. Every summer crowds gather to watch the sight of costumed interpreters bringing him back to life in jousting matches and re-enactments. But this image of the knight - the mounted warrior armoured head to toe, bedecked with brightly painted heraldry and mounted on a great charger — is only a snapshot of what the real knight was. The full picture is much more complex. His outward appearance changed over the 500 years of his dominance, as armourers responded to the developments in weapons technology and took advantage of the changes in metallurgy and smithing techniques. The figure he cut in the 11th century — clad in unadorned mail with a nasal helm on his head - was vastly different from that of the 14th, where the mixture of plate and mail was hidden beneath a flowing surcoat and his face was covered by a full helm or the beaked visor of the more lightweight luwcinet; which was as different again from the way he looked as his time on the battlefield came to an end in the 16th century — massively armoured in full plate under a sleeved tabard, with his visored helmet topped with plumes of ostrich feathers. Nor did knights charge hell-for-leather into combat. Whilst the evidence for the tactics used on the battlefield can be frustratingly vague it is clear that, when executed correctly, charges were carefully timed and structured using small-unit tactics to maximize their impact and allow for reforming and the use of reserves. The importance of being ordinate — in good order — and the dangers of being inordinate are regular themes in battle narratives. Knightly commanders could be rash and arrogant, it is true, but they could equally be cunning and careful. The knight's skill was not limited to mounted combat and the knight was as effective a warrior on foot as he was on horseback. The Anglo-Norman knights of the 12th century and the English men-at-arms of the 14th and 15th fought their pitched battles on foot more often than they did on horseback, and other nations' warriors might do the same. Contrary to the traditional view, a knight knocked out of the saddle did not necessarily become as helpless as a turtle on its back, although in certain 8 INTRODUCTION -<}> circumstances he might be at a disadvantage. The armour he wore was purpose built and represented the finest in medieval engineering and craftsmanship. The knight had to be fit, to be sure, but his armour by no means rendered him immobile. The knight was the complete warrior of the middle ages. Not surprisingly, the popular image of the knight is an almost wholly martial one, but the knight was far more than just a warrior. The knight was a part of a martial elite largely because he and his companions formed the social and political elite too. This gave him not only the finances and resources to equip himself with the armour, weapons and mounts that made him so formidable, but also the leisure to be able to train and hone his skills in the hunt and on the battlefield. It also gave him a sense of his own superiority; the arrogance of the knight could lead him to achieve tremendous things but also to make tremendous errors. Understanding the knight's place in society and politics is a more difficult proposition than understanding his military function, but it is no less important. Not only could he be a landowner administering his own estates, he might also serve as a royal officer, acting as juror or judge or a commissioner performing administrative tasks that seem far removed from his martial background. Just as his martial appearance evolved so too did his social status. In the 1 1th century knights were little more than armed servants, their status low. By the 12th century they had risen up the ranks and every lord was a knight (even if every knight was not a lord). By the end of the 13th century the ordinary knight was being called upon to advise monarchs in parliaments. By the 14th century the distinction of the knightly class was already being eroded as lesser men - the esquires and gentry' — began to live, serve and behave as the knight did. By the 16th century these lesser men were being knighted, whilst others achieved the same status by service within royal households that now prized courtliness and political acumen over martial ability. The knight had a rich and vrbrant culture. He was both literate and intellectual. Many knights were writers, and have left us with tales of great deeds or chronicles of the events they had witnessed and people they knew. Others produced legal and religious discourses which show a contemplative and sensitive nature that belies the brutality of their vocation. Their money was spent on fine clothing, music and gardens as much as on fine arms, armour and horses. Of course there was a link between their cultural tastes and martial background. Many of the tales that they listened to were about the deeds of mythical heroes and champions performing great deeds of valour in battle. But these characters were lovers as well as fighters. The stories are often as much about the ladies they loved as about the battles they fought. They can have a religious element too. The Church increasingly sought to redirect and limit the violence and vanity of the warrior by shaping knightly culture in an image more pleasing to itself. 9