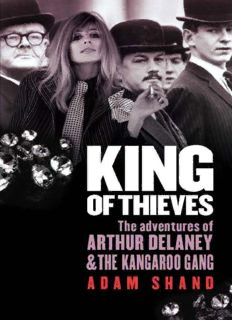

King of Thieves. The Adventures of Arthur Delaney and the Kangaroo Gang PDF

Preview King of Thieves. The Adventures of Arthur Delaney and the Kangaroo Gang

King of Thieves King of Thieves Adam Shand For my children Noliwe and Jack. And for those who live in the moment. 22 June 1990. New Bond Street, London W1 T he long journey had returned the King to where his legend had begun. Lost to authorities in transit, the master thief was back in London. He should have been in a jail cell in Australia, but events had taken a different turn. The next few minutes would write the final chapter of his story, he thought. For now, he was free, walking through the most expensive shopping precinct in the world. En route to the biggest job of his career he felt no fear, just a calm and clear resolve. There was no plan in his mind, only the outcome he desired. The ‘how’ was already in his pocket, a flat piece of lead, the size of a key. What mattered now was to move with the f low without hesitation and to react instinctively to the slightest change. It was a state of mind beyond confidence. It was an acute awareness of everything and everyone around him, even of the energy moving unseen between people. It was an aerial view of the scene. The thief would contrive a moment when he could simply disappear. After 40 years and countless hundreds of jobs, the King was still hoisting to survive—just as he had when he learnt the trade in Sydney. He had never had a bank account or a mortgage, much less owned a home. He lived from a suitcase, hotel to hotel across the globe. Always travelling—always working, gambling, drinking and philandering in an endless cycle. There was no trace of an Australian accent anymore. You would have sworn he was English, a proper gent in his hound’s-tooth jacket. He carried no papers. The well-used passport stored in a bank safe deposit box identified him as James Duffield, 60, a native of North London. But that James Duffield had never left the country. He had never been beyond Southend-on-Sea, in fact. ‘Jimmy Duff ’ was a regular drinker at the Crowndale, a pub in Chalk Farm once notorious as HQ for the best thieves in London and much else besides. The man strolling down Bond Street this grey summer morning was of a different cut. He exuded worldliness, he was a globetrotter, perfectly dressed and groomed. He had left Australia as the Duke in 1962, but now, by virtue of his style and record, he liked to be known as the King. Few would argue. There was a courtly sway from the hips in his walk, reminiscent of the Bond Street loungers of the seventeenth century, the foppish wasters who paraded themselves like gentlemen around Mayfair. A lounger was derided as ‘a man with two suits’ back then and that aptly described the King 300 years later. At 60 he wasn’t up for running. Beneath the floppy hair and tailored clothes, he was gaunt and thin, hollowed out by cancer, but in remission he would have his gaunt and thin, hollowed out by cancer, but in remission he would have his moment, one last hurrah in Mayfair. He was the last of the Kangaroo Gang—the King with his small band of subjects. Most of the Aussies had been cleaned out by the cops or gone into the drug business years before. Many were dead, some of the best of them. In the mid 1960s the Kangaroo Gang had been 60-strong, a network of mercenaries working for five master thieves, elusive, ever changing, a parade of career criminals in their prime. Add to that a bevy of young Australian women seeing the world for the first time. Most of them would return to Australia to lead honest productive lives, but for a short, fabulous time they would enjoy an experience straight out of the movies. Perhaps it was the age or it was something special in these men and women that gave them such confidence. For a dozen years, they had run amok across the globe stealing jewels, furs and any luxury item they could lay their light fingers on. Their success and how it was achieved seems unbelievable, mythical almost. They had stolen more than a hundred million pounds worth of treasure in broad daylight. There was no violence, never a firearm was drawn or even carried. They had never so much as broken a window during a job. It was hard to believe, but the King had been there from the beginning and had seen it all. Now, of the master thieves, only he, Arthur William Delaney, remained. With him today were the remnants of the Kangaroo Gang. ‘Petite Philippe’, a disinherited French count, walked beside him flashing his Gallic charm at women passers-by. The others were coming at the target from various directions. It would not pay to approach in one group. There were a couple of Australians still; John ‘Bimbo’ James and ‘the Colonel’ had been with Arthur since the 1970s. Some ring-ins took the raiding party’s total complement to ten, enough to control the scene. Arthur took his time strolling down New Bond Street. He glanced at his reflection in the windows of the fine stores: Cartier, Dior, Watches of Switzerland, Piaget, Chopard, Van Cleef & Arpels, Yves St Laurent, Gucci, Tiffany and Graff Diamonds. He had robbed them all over the years, if not here, somewhere around the world. Many of the old names were long gone, but there were new brands to replace them, beautiful new treats to mesmerise and captivate. It had always puzzled Arthur why anyone would waste time on ancient ruins, musty art galleries and museums when there were sights like these to enjoy. The street had changed for sure. They hadn’t seen him coming in those early The street had changed for sure. They hadn’t seen him coming in those early days. They hadn’t imagined a thief like Arthur could exist. But in 1990, Mayfair was ready for him, or so the Bond Street Association believed. At every door a burly shop detective stood watch, scanning the street for anything sinister. The former policemen and ex-soldiers kept in contact through their earpieces, relaying observations up and down the street. Any suspicious characters would be noted and tracked before they got halfway down the narrow one-way street. But the thieves were in fact a secondary concern that day. The West End was on high alert as the Irish Republican Army had stepped up its campaign of London bombings in support of self-rule in Northern Ireland. A month earlier, the IRA had detonated a bomb under a mini-bus at Wembley, killing a soldier and injuring another. A month later, the Irish bombers would strike the London Stock Exchange two and a half miles away, blowing a ten-foot hole in the wall. In 1993, after a string of IRA attacks, authorities would create the ‘Ring of Steel’, a network of street-based surveillance cameras around the financial district and the West End which would change life in London forever. In 1990, you could still walk the streets of London without being filmed every few steps as you are today. You could still manipulate reality, if you understood a few simple laws of perception. In a busy street, it’s the person standing still that gets noticed. A piece of wood standing in a fast flowing stream creates an eddy before it that draws the eye. Everything else passes unseen. The amateur thief on Bond Street who stops and hesitates before entering a store has failed before he begins. In his demeanour, he has communicated his anxiety, a sense of impending doom. The more he is noticed by security the more fear he exudes. The professional thief can use this to his advantage. Standing sentry on a fine jewellery house where the prices (not to mention the toffy staff ) exclude 99 per cent of the population is a boring, tedious job. After a while the flow of people must indeed seem like a river, the eddy around the stationary object is a welcome relief to the eye. The diversion allows the thieves to pass right by. As he crossed Conduit Street, where New Bond becomes Old Bond, Delaney could see his destination. This day had been coming since 1962. For all that time he had dreamt of knocking over this store. Asprey was not just an institution but a statement of English achievement. Since 1781, Asprey had offered ‘articles of exclusive design and high quality, whether for personal adornment or personal accompaniment, to endow with richness and beauty the tables and homes of people of refinement and discernment’. It had begun as four separate shops connected by a central discernment’. It had begun as four separate shops connected by a central courtyard. It had been consolidated into one and enclosed by a single roof. Now it sat there brooding and substantial on the corner of Old Bond and Grafton streets, a parade of archways framing gleaming windows, a mirror for passers-by to judge their unworthiness. Looking up, a royal coat of arms: ‘By Appointment to H.M. The Queen, Goldsmiths, Silversmiths & Jewellers’ reinforced the message. When the Duke of York, Prince Andrew, had married Lady Sarah Ferguson in 1986, the wedding gift list had been posted at Asprey. One of the Rolling Stones had spent £30 000 on an engagement ring here. There were no cheap souvenirs to pull in tourists like Harrods had been forced to offer over at Knightsbridge. A box of Christmas crackers cost £500. Other Australians had pulled off jobs at Asprey, but nothing on the scale that Arthur intended. In 1985, another Australian had slipped a sterling silver elephant worth £7000 into his pocket as he left Asprey, but he got nabbed later. He told police the commissionaire Tom Farra had told him to have a nice day. He replied that he already had. He got seven years’ jail and was deported for his trouble, never to return. Everyone said the Kangaroo Gang was now defeated, its modus operandi a quaint reminder of a bygone era. Arthur and Petite Philippe approached the double semi-circular doors of Asprey. Only the uniformed figure of the commissionaire stood between them and the rich interior. Farra had seen these men before; in the weeks prior, they had been in several times. He had been greeting people like this his entire career at Asprey—well-dressed, classy, relaxed people. He could smell a phoney but as Asprey had described its customers in 1851, Arthur and Philippe were obviously ‘people of refinement and discernment’. Farra stepped to one side and the double doors glided open. A warm rich aroma of fine leather and cologne enveloped them immediately. If rich had a smell this was it. A few years earlier writer Christopher Long had imagined himself a thief standing on the same celebrated spot: [Stretching] into the distance, is one of the most sensational sights to be seen in London. Gleaming, glittering, enticing and beguiling is a vast expanse of unique craftsmanship in gold, silver, leather, porcelain, glass, brass, precious stones and rich mahogany. To the right is modern silver, jewellery, watches and the innumerable small, exquisite items that range from money-clips to bejewelled shirt-studs; from cuff-links to the first item on my shopping list—a £15,000 gold wristwatch with a perpetual calendar—so rare that Asprey’s only have two or three for sale each year. Beyond that is the exotic and self-explanatory Gold Room leading on to displays of birds and beasts in gem-encrusted precious metals that are the unique products of Asprey’s own workshops three floors above. Standing at the doorway and looking straight ahead is the sumptuous staircase which leads to

Description: