Kamba Ramayana PDF

Preview Kamba Ramayana

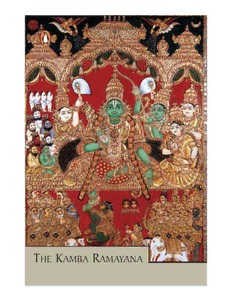

TRANSLATED BY P.S. SUNDARAM Kamba Ramayana Edited by N.S. Jagannathan PENGUIN BOOKS Contents About the Author Preface Introduction A Note on Translation Bala Kandam Ayodhya Kandam Aranya Kandam Kishkinda Kandam Sundara Kandam Yuddha Kandam Notes and References Glossary Copyright Page PENGUIN BOOKS KAMBA RAMAYANA P.S. Sundaram, who took his Master’s degree in English Language and Literature from Madras University (1930) and, later, from Oxford (1934), had a long and distinguished career as a professor of English at Lahore, Cuttack, Bareilly and Jaipur. For a short stint in between, he was Member, Public Service Commission, Orissa. He is the author of two books on R.K. Narayan and has translated an impressive array of Tamil classics into English. In addition to the present work, he has translated into English selected poems of Subramania Bharati, Tiruvalluvar’s Kural, Andal’s Thriuppavai and Nachchiyar Thriumozhi. N.S. Jagannathan holds a First Class Master’s degree in English Language and Literature from Madras University. After a few years of college teaching and a stint in the Civil Service, he became a full-time journalist, working successively in senior positions in the Hindustan Times, the Statesman, the Financial Express and the Indian Express. He retired as Chief Editor, the Indian Express, in 1991. Preface My acquaintance with Professor P.S. Sundaram (1910–1998) began decades ago when, just out of the university, I appeared before the Orissa Public Service Commission for a job in the English department of the Ravenshaw College, Cuttack. As Professor of English in that college, he was the expert among members on the Selection Board. He put me through the wringer with a certain detached cruelty, dictated no doubt by his anxiety to ensure that his future colleague was not a dud. I got the job and thus began a life-long friendship that has been one of the great blessings of my life. Ravenshaw College was founded in the nineteenth century and is one of the oldest and among the highly regarded Indian educational institutions. Being the only government college in Orissa at that time, it has been the alma mater of innumerable distinguished sons of Orissa and has had some of the finest teachers of the country. In my time, besides Sundaram, there was in the English department the genial V.V. John, an irrepressible wit who hid a profoundly serious mind behind an apparent air of levity and high spirits. My own stay in Orissa was a brief one, lasting less than sixteen months. But during this short period, both John and Sundaram exercised a profound influence on me, not only in the shaping of my literary tastes but also in instilling in me the ineffable values of a civilized, intellectual freemasonry. They were much older than me and I, had I lived in Cuttack instead of Madras during my college years, would have been their student. But in their attitude towards me, there was no trace of condescension or hierarchical snobbery so familiar in Indian academia. In the best traditions of Oxford where both were educated, they treated me, a callow youth though I was, as an equal. To my utter consternation, Sundaram made me teach postgraduate classes in Elizabethan literature of which I, then had only the haziest notions. I had to bone up on much dull and wearying stuff trying to live up to his, if not to my students, expectations. In the years following, when my own wayward career did not permit me to be in daily contact with Sundaram, we were in regular touch, writing to each other and meeting from time to time. Such meetings were more frequent in his later years when he moved to Madras and always stimulating, our discussions ranging over a wide area. For example, Sundaram was fiercely Anglophile, the consequence of the stereotypes implanted in his mind by his deep love of English literature and the example of some of the great Englishmen that taught him in India and at Oxford. On the other hand, though I shared with him a love for English literature, I was bred on a different perception of the benefits of the Raj. This was one of the perennial themes of our heated exchanges, conducted on his side with exemplary urbanity and generosity to a much younger man. Sundaram’s academic credentials were of the highest. A brilliant student of Presidency College, Madras, he got a first class Master’s degree in English literature in 1930. As was the almost settled routine of gifted students of the times with a Tamil Brahmin middle-class background, he went to England to join Oxford and, simultaneously, sit for the ICS examination. He tried twice to get into the ICS but on both occasions narrowly missed being chosen to the service, standing fourth or fifth in the ranking. (Unlike in post-Independence India, when selections for the services by competitive examination were a case of mass recruitment in hundreds, those were parsimonious times, with hardly more than five or six being chosen.) So, Sundaram returned to India in 1934 with a degree in English literature from Oxford and launched on a distinguished career as an academician in DAV College, Lahore, in 1934. He joined the Ravenshaw College, Cuttack, as professor in 1938 when he was barely twenty-eight, perhaps the youngest head of the English department at that time. Unlike John and I, Sundaram stayed on in Orissa for over twenty years, giving the best years of his life to the state, as professor, principal and, from 1953, a Member of the Orissa Public Service Commission. By one of those quirky Constitutional provisions, when his term with the service commission ended in 1959, he could not go back to the government in any capacity. Then in his mid- forties, Sundaram was obliged to seek non-government employment elsewhere. He left Orissa to become Principal of the Bareilly College, and still later, of the Maharani’s College, Jaipur, from where he retired in 1974. It was only then that he could return to his first love—classical Tamil literature, which he had perforce put on the back-burner because of his teaching and administrative duties. A lifelong engagement with English literature had given him a profound understanding of all aspects of literary imagination. This enabled him to bring to the study of Tamil literary classics a mind uncluttered by the hang-up of traditional Tamil scholarship. As a result, he was able to apply to these works the categories of a wider and universal aesthetics and poetics. His total command of both the Tamil and English idiom enabled him to embark on a translation enterprise, that, in the retrospect of his actual accomplishment, seems formidable, almost, rash, in its ambition. Obviously, it is a case of one thing leading to another, rather than a premeditated project. Starting with the modern poet, Subramania Bharati, Sundaram took on, successively, Tirukural of Tiruvalluvar and then the mystical poems of Andal and other Aazhwars in the Vaishnavite Bhakti tradition (the last two have been published by Penguin). The last years of his life were taken up with the translation into English verse of the whole corpus of some 12,000-odd verses of the renowned Tamil classic Kamba Ramayana. In itself an awesome feat, considering the hazards of the enterprise, it was, to use the language of the Ramayana, the crest-jewel of his brilliant career in translation. N.S. Jagannathan Introduction I THE GENE POOL1 OF THE RAMAYANA MYTH ‘Perhaps no work of world literature, secular in origin, has ever produced so profound an influence on the life and thought of a people as the Ramayana,’ wrote A.A. Macdonell in the Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics. The unbroken continuity of the Ramayana myth to this day is indeed unique. There is no comparable visible or aural evidence of the presence of the Hellenic heritage in the daily lives of Europeans. Of the other, Hebraic, strand of their cultural inheritance, except among those highly educated in the humanities stream, it would be difficult to find anyone who remembers the details of the Old Testament. This is in stark contrast to the way the story of Rama has been burnt into the memory of every Hindu child, and the invisible presence of the myth in the daily lives of the people. To choose a trivial example, unlike in the West where names may or may not have meanings, children in India, specially in the south, are named directly after Rama or Krishna. The latest issue of the Chennai telephone directory contains over 21,000 entries of Rama and its variants like Ramswami and this does not include Raghava and its variants like Viraraghava. In addition, you have Lakshmana and Bharata in legion, and less frequently, Satrughna. Likewise, Sita and its variants are a favourite name, at least until recently, for the girl child. It is an indication of total and ultimate assimilation that these names are uttered without a consciousness of the epic story. (This practice has an interesting reason. There is a famous story of Ajamila, a brahmin turned profligate, who had forgotten his piety and lived a dissolute life. On his deathbed, he called out ‘Narayana’, his favourite youngest son, for a last embrace, with no thought of the Primal God of that name. And yet, because he uttered the lord’s name with his last breath, all his sins were cancelled and the messengers of Yama couldn’t claim him for hell.) Thus has the Rama story become part of the texture of the collective unconscious, half remembered, if at all, but within easy recall of the Indian people. And there is no lack of other reminders of the myths. There is, for example, the pervasive presence of temples in south India, some of which were built as early as the ninth century. Their titular deities are specifically named after Rama and worship is carried out in the prescribed manner to this day. The famous Ramaswami temple at Kumbakonam in the Thanjavur district of Tamil Nadu is one example among many. These towering temples dominating the locale are a constant reminder of Rama, even if you did not visit them. Temple-associated sacred art has produced magnificent paintings of the Rama story (as on the walls of the Ramaswami temple, already mentioned) and bronze sculptures such as the ‘Panaiyur Rama’ (in the Chennai museum) and others in actual worship at Vaduvur and Tillaivalakam in the Thanjavur district. Historically, the temple culture grew as part of the Bhakti cult of the personalized God that had its origins in south India and spread northwards in the post-upanishadic period of Hinduism. Vaishnavaite and Saivaite mystics in the centuries after Christ were precursors of the formalized Bhakti element in Hinduism. Vishnu and Siva, until then minor gods in the vedic pantheon, overshadowed other gods like Indra and Agni and attained, gradually, the status of members of the primordial Trinity of Brahma, Vishnu and Siva. Of the three, Brahma was in course of time subsumed by Vishnu and became marginalized. (There are only a few temples for him, one in Ajmer in Rajasthan, and a minor shrine in Tamil Nadu.) It is true that latter-day popular religion had myriad gods and goddesses, but they are not the vedic ones and they derive their authority from their association, one way or another, with Vishnu and Siva. The emergence of the Bhakti cult, of a mystical personal love of incarnate God, decisively transformed the Hindu faith. It not only demoted the earlier pluralistic pantheon of gods but also radically modified the late vedic, upanishadic philosophic abstraction of the Brahman or the formless Primal God. This was facilitated by the emergence of the concept of the avatar (‘coming down’), memorably and authoritatively expressed in the fourth chapter of the Bhagavad Gita: ‘Whenever Dharma becomes decadent, I incarnate myself to destroy unrighteousness triumphant.’2 The ten incarnations of Vishnu form an evolutionary sequence from fish to tortoise to boar to man- lion to dwarf to a fully developed anthropomorphic god like Rama, the sixth incarnation, followed by Krishna, and Kalki (yet to come) who will destroy the universe before the birth of a new cycle of creation. (A fanciful identification of this event by some is the nuclear holocaust to come.) Arising out of this neo-Hinduism, based on a personal God, and the immense output of devotional literature and associated new theology, there came into being a wider and popular methodology of public discourse that persists to this day. An important aspect of the Bhakti movement was its popular base and egalitarian thrust which considerably eroded the harsher aspects of the caste hierarchy. God became accessible to all by the passionate devotional poetry in the vernacular of inspired mystics, some of whom belonged to the lesser castes, including the untouchable ones. In the south, the tradition of public discourse or pravachanam (expounding) had two streams. One was a vehicle of theological disputation and the other of popularization, at least from the days when the Bhakti cult had crystallized into the Srivaishnava doctrine of prapatti or total surrender to God. Great commentators like Peria Vachchan Pillai, Manavala Mamuni, Vedanta Desika and their disciples with different sectarian and doctrinal positions regularly used the Ramayana—episodes from it rather than the whole of it—in their, often acrimonious, disputations. The Tenkalai (southern school) and the Vadakalai (northern school) of Ramanuja’s theological view of vishistadvaita or ‘modified monism’ in opposition to Sankara’s advaita or ‘absolute monism’ were often locked in arguments over the subtle nuances of their common faith. For example, a crucial doctrinal difference between the two was on the concept of prapatti or absolute surrender to God mentioned earlier and the nature of ‘grace’. If one simplifies it greatly, the Tenkalai doctrine of grace was somewhat similar to the Calvinist concept of ‘efficacious grace’ of God but without the implication of predestination. God’s grace ‘bloweth as it pleases’ regardless of just deserts: even sinners may be blessed with it, while the virtuous may not. The Vadakalais dispute the randomness of such arbitrary bestowal of grace and insist on deserving it.3 In these controversies, episodes from the Ramayana, such as that of Bharata ruling with Rama’s sandals as a surrogate for Rama’s sovereignty, Rama’s friendship with Sugriva, Vibhishana’s taking refuge with Rama, were subjected to ingenious interpretations in terms of their particular doctrines on the subject. The second and popular version of the Ramayana discourse is what has come to be known as the Kalakshepam, or Harikatha (the latter an importation from Maharashtra into Tamil Nadu in the late eighteenth century). It was a form of musical discourse, giving ample scope for deconstruction of the Rama legend, in which the several written and oral versions were freely retold and reinterpreted as suited the local value system and body of beliefs. Literacy being low and texts limited in number in palm leaf and its substitutes in pre-print days, the oral tradition was strong. The unlettered had access to the Rama legend only through recitation and listening to kathakars (storytellers). It was a very effective form of adult liberal education. Strong mnemonic traditions were built this way and the Ramayana was quietly internalized by the bulk of the population, with music and narrative skills combining to hold hundreds of listeners in thrall in temple yards and elsewhere. The tradition has been so strongly entrenched in people’s consciousness that it has become a part of proverbial folk wisdom. This is tellingly exemplified in the famous Tamil quip about the ignorance of the man who, having heard the Ramayana story all night, asked the next morning whether Rama was Sita’s uncle. Equally important in imprinting the Rama consciousness in the psyche of the people was the role of classical Carnatic music, where episodes from the Ramayana formed a major verbal component of the concerts that are an integral part of the cultural life of elitist Tamils. The moving compositions of Saint Tyagaraja (circa late eighteenth-nineteenth century), the most eminent of Carnatic music composers, draw freely from Ramayana episodes such as, for a random example, Rama’s encounter with the tribal woman, Sabari. In addition, they breathe an impassioned personal intimacy with Rama.4 Another facet of the pervasive presence of Rama and the Ramayana in the daily life of south Indians is associated with their domesticities and the ambience of their homes. Lithographic prints of the original paintings of the royal painter Ravi Varma on Ramayana themes and other reproductions of kitsch art on the same subject are part of puja rooms and even the more secular space of the living room walls. The intimacy of popular art with Ramayana is also seen in the famous Tanjore paintings with their gemstone-set picturization of Ramayana themes, most notably of the Pattaabhishekam (coronation) of Rama after his triumphant return from exile. A different aspect of the internalization of the Ramayana in the domestic life of the people in south India is to be seen in the routine teaching of music to girls from middle-class homes. Till about a few decades ago, households used to resound, morning and evening, with the music teacher drilling young girls into the elements of Carnatic music, largely with Tyagaraja’s compositions in praise of Rama. Some of this music rubbed off aurally on boys (who were themselves not formally taught music) and formed their musical taste—and Rama consciousness—that they carried well into their adulthood.