Judaism and Homosexuality - An Authentic Orthodox View PDF

Preview Judaism and Homosexuality - An Authentic Orthodox View

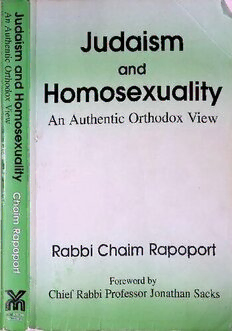

■ > = c > a Judaism 5 Q 2 C/> o —' and 9Q r4 T o a Homosexuality o s;2 s 3 An Authentic Orthodox View « 2 o in (D X c Q » |! l ii ‘ i o o Rabbi Chaim Rapoport o O' o Foreword by Chief Rabbi Professor Jonathan Sacks fn vy/_\!L‘ K JUDAISM AND HOMOSEXUALITY An Authentic Orthodox View RABBI CHAIM RAPOPORT Foreword by Chief Rabbi Professor Jonathan Sacks Preface by Dayan Berkovits VALLENTINE MITCHELL LONDON • PORTLAND, OR First Published in 2004 in Great Britain by VALLENTINE MITCHELL Crown House, 47 Chase Side Southgate, London N14 5BP and in the United States of America by VALLENTINE MITCHELL do ISBS, 920 N.E. 58th Avenue, Suite 300 Portland, Oregon 97213-3786 Website: httn://www.vmhooks.com Copyright © 2004 Chaim Rapoport British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Rapoport, Chaim, Rabbi Judaism and homosexuality: an authentic orthodox view 1. Homosexuality - Religious aspects - Judaism I. Title 296.3'66 ISBN 0-8530-3452-4 (paper) ISBN 0-8530-3501-6 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publicarion Data Rapoport, Hayim. Judaism and homosexuality: an authentic orthodox view/Chaim Rapoport; with a foreword by Jonathan Sacks, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-85303-452-4 (cloth) 1. Homosexuality-Religious aspects-Judaism. 2. Orthodox Judaism-Doctrines. 3. Pastoral psychology (Judaism) I. Title. BM729.H65R37 2003 296'.086'64-dc21 2003057164 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher of this book. Typeset in 11/13pt Sabon by Vitaset, Paddock Wood, Kent Printed in Great Britain by MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall Contents Foreword by the Chief Rabbi vii Preface by Dayan Berkovits xi Author’s Preface XV Acknowledgements xix Approbations xxi 1. The Prohibition of Homosexual Practices 1 2. The Nature of Homosexuality - A Jewish Perspective 18 3. The Formidable Challenge 36 4. Attitudes to the Practising Homosexual 48 5. Understanding and Judgmentalism - A Synthesis 68 6. The Child’s Cry 76 7. Procreation and Parenthood 90 8. Questions and Responses 101 9. Summary and Conclusion 134 Notes 137 Bibliography 200 Index 221 Index of names 227 Foreword At the heart of Judaism is a remarkable idea, that first an individual, then a family, a tribe, a collection of tribes and then a nation entered into a covenant with God to live a life faithful to His word. It would become, in the biblical phrase, a ‘kingdom of priests and a holy nation’. Its collective existence would be devoted to ‘righteousness and justice’ on the one hand, ‘holiness’ on the other, and by its dedication to these ideals it would become a living witness to God’s presence in the world. Needless to say, these were high standards to live up to, and much of Jewish literature is marked by candid acknowledgement of Israel’s shortcomings. Yet in no small measure that is what the people became. Few in numbers, insignificant in power, dispersed and all too often persecuted, they kept faith with the covenant and took immense care to hand on their values to future generations. The chapter they wrote in the history of mankind is a moving testament to the fidelity of the human spirit in response to the call of God. One of Judaism’s fundamental beliefs is that the God of revelation is also the God of creation. There is, in other words, a deep congruence between the life we are called on to lead (revelation) and the universe in which we are called on to live it (creation). Judaism is neither an abandonment of the world nor an abandonment to the world but a struggle to establish God’s presence within it. To put it another way, Judaism is neither a renunciation of pleasure (asceticism) nor an amoral pursuit of it (hedonism) but a way of life that sanctifies pleasure by dedicating it to God and to the wider values of the covenant as a whole. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Judaism’s understanding of sexuality. There have been cultures marked by a profound distrust of sexuality, seeing it as a shameful acknowledgement of the physicality of human existence, to be foregone in pursuit of a more spiritual, other- viii JUDAISM AND HOMOSEXUALITY worldly life. From this came the concept of a monastic existence and the adoption of celibacy as an ideal. At the opposite extreme are cultures that embrace sexuality as the celebration of the physical, in contradistinction to the spiritual, divesting it of any higher purpose than transitory pleasure, unaccompanied by lasting commitment or responsibility. The secular West is passing through such a phase today. Judaism rejects both alternatives, for each contains only half the truth of the human situation. We are physical beings, embodied selves, part of nature, or as the Torah puts it, ‘dust of the earth’. But we are not onlv physical beings. We are self-conscious, reflective persons, capable of moral choice. There is within us the ‘breath of God’. In a bold and original challenge to humanity, the Torah invites those who heed its call to combine sexuality with spirituality. Hence the unusual significance of sexual ethics within the Jewish way of life. Judaism is not puritanical. It does not condemn sexual pleasure; it values it. But Judaism is not hedonistic either. It does not believe that, in a covenantal life, one can divorce pleasure from the moral framework in which it takes place. The institution which the Torah sets forth as its ideal is marriage - not marriage as a social convention but as the human counterpart of Israel’s covenant with God. In marriage, man and woman pledge themselves to one another in a bond of love, and in and through that love bring new lives into existence. The prophets - Hosea, Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel - saw marriage as the supreme metaphor for God’s relationship with His people. The I-and-Thou between man and wife mirrors the I-and-Thou of God and mankind. It need hardly be said that there are few aspects of Judaism more out-of-step with today’s radically individualistic culture than its view of sexual ethics. That, however, has always been the fate of one or other element of Jewish life. To be a Jew has always involved being willing to challenge the idols of the age, whatever the idols, whichever the age. One of the idols of our time is the idea of the sovereign self, navigating the world with no binding commitments beyond personal inclination and private desire. Today’s secular culture resists the idea that there may be boundaries to the life we may legitimately pursue. It finds it difficult to understand that the logic of ‘I ought’ is quite different to that of ‘I feel’ or ‘I want’. At such times, Judaism’s ethics become counter-cultural. To live by the call of Torah is not an easy undertaking. At times, it is little short of heroic. This is particularly so for those with a homosexual orientation. The FOREWORD ix Torah forbids homosexual activity as such: that much is clear from the testimony of both biblical and post-biblical literature. It does not condemn a homosexual disposition, because the Torah does not speak about what we are, but about what we do. It does, however, ask of one who has such a disposition to suppress or sublimate it and act within the Torah’s constraints. What this might involve requires case-by-case counselling: homosexuality is not a single phenomenon but a spectrum of conditions and existential circumstances, and sensitive advice is needed for each individual. Whatever the counsel, however, none of us should under-estimate the difficult journey he or she may have to make. For most, it will be fraught with immense pain. Just as the Torah asks of the homosexual to wrestle with his or her sexual desires, however, so too it asks of the rest of us to understand his or her plight, caught between two identities and two cultures. I, for one, can never forget the fact that lesbians, gay men and bisexuals as well as Jews, were the victims of Nazi Germany and remain the object of prejudice and misunderstanding today. As Jews, therefore, we have special reason to be on our guard against attitudes, words and behaviour that give needless offence or in any other way add to the trauma of those already fraught with great internal conflict. Stereo typing, homophobia and verbal or other abuse are absolutely forbidden. Jewish law and teaching condemn in the strongest possible terms those who shame others. ‘One should rather throw oneself into a fiery furnace’, said the sages, ‘than humiliate someone else in public.’ It is not enough to know that something is forbidden. Our full humanity requires of us that we understand the difficulty - physical, psychological, even existential - that individuals may experience as they engage in inner struggle between instinct and obligation, desire and duty, personal emotion and religious imperative. Compassion, sympathy, empathy, understanding - these are essential elements of Judaism. They are what homosexual Jews who care about Judaism need from us today. That is what lies behind Rabbi Chaim Rapoport’s book. It is a sensitive, thoughtful work on a subject too often either ignored or treated superficially. Although it contains an impressive array of halachic sources, its subject is less halachah than pastoral psychology; not, what is permitted and what forbidden, but how shall an individual cope with profound dissonance between what he feels himself to be and what Judaism calls on us to be. No one should under estimate the depth of that conflict. It is real and painful, sometimes to the point of depression and despair. There are homosexual Jews who X JUDAISM AND HOMOSKXUALITY care deeply about Judaism, who seek to live by its laws and ideals, but at the same time need counsel from someone who has made the effort to listen, enter into their struggle, and find the words which, while not dissolving the problem, ease some of its loneliness and emotional confusion. What makes Rabbi Rapoport’s book invaluable is that he has understood this. He is a courageous figure who has written on a difficult subject that many would rather avoid. Parts of the book will be contro versial. As he himself indicates at various points, there are halachic authorities who take a view different from his own. Nonetheless, this is a work of genuine psychological depth and insight. We pray, in the kaddish de-rabbanati, for rabbis to be blessed with ‘grace, loving kindness and compassion’. In Rabbi Rapoport we have such a man. Judaism can rarely be internalised without prolonged inner struggle. Many of the Psalms speak directly from this tempestuous emotional realm. According to the Torah, the Jewish people acquired its name only when Jacob, alone and afraid, wrestled at night with the angel that had no name. ‘Israel’, the name he was given after that contest, means ‘one who struggles with God and with mankind and prevails’. The great thinkers of Judaism have always known that it is not a faith that brings serenity or peace of mind. The religions that promise these things purchase them at great price: a withdrawal from engagement with the conflicts and challenges of a life that seeks to refashion the physical in response to the spiritual. Judaism never lets us rest because it holds before us two conflicting realities - the world that is and the world we are called on to make, the ‘I’ of human desire and the ‘Thou’ of God’s call. From that cognitive dissonance comes the ‘strife of the spirit’ in which true greatness is born. Those who read this book will not discover that this strife can suddenly be resolved. They will, however, know that in Rabbi Chaim Rapoport they have found a sensitive and sympathetic spirit, prepared to address a real and painful conflict with honesty and the best available guidance; that, in short, they are not alone. This is an important and courageous book, urgently needed, well written, thoroughly researched, and graciously conceived. I congratulate its author. May it bring under standing and insight to all who read it. Jonathan Sacks Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth Preface This is an important and challenging book: probably the first meaningful attempt to articulate a strictly Orthodox perspective on the question of homosexuality. It is written be’safah bemrah u’vin’imah - in a manner which is clear and uncompromising as to halachic values and norms, yet at the same time compassionate and sensitive to the needs of those who find themselves in a religious predicament because of their sexual proclivities. Rabbi Rapoport is to be congratulated for his courage in tackling a topic which is so unenviable in its complexities. The book is a valuable academic study, with a multitude of refer ences and wealth of information. Simultaneously it serves as a practical guide to help rabbis, and others, relate to the homosexual in our midst. Rabbi Rapoport does not shrink from facing up to the difficult issues. The flavour of the book can perhaps best be gleaned from the chapter entitled ‘Questions and Responses’. This chapter, responding as it does to input from the general community, gives us a wide insight as to the complexities of the issues, and the nature of the concerns which need to be addressed. Not everybody will agree, of course, with all of Rabbi Rapoport’s conclusions, or even with the direction of his arguments. There will also be some, no doubt, who are uncomfortable with the book as a whole, or who may think that it should not have been written and publicly disseminated. We grew up, after all, in an age (or so it seemed), of comparative innocence, in which sexual matters were not openly discussed. And even if some topics were not beyond the pale, one recoiled, instinctively, from talking about homosexuality. We can, however, no longer afford the luxury of avoiding the unpalatable. The book is important, because it is timely and