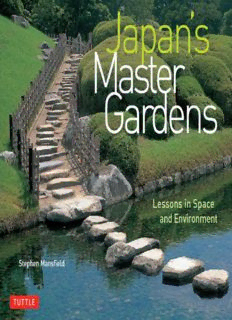

Japan's Master Gardens: Lessons in Space and Environment PDF

Preview Japan's Master Gardens: Lessons in Space and Environment

Japan’s Master Gardens Lessons in Space and Environment Stephen Mansfield TUTTLE Publishing Tokyo | Rutland, Vermont | Singapore Published by Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd www.tuttlepublishing.com Text copyright © 2011 Stephen Mansfield Photos copyright © 2011 Stephen Mansfield All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mansfield, Stephen. Japan’s master gardens: lessons in space and environment/Stephen Mansfield. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN: 978-1-4629-0852-3 (ebook) 1. Gardens, Japanese--History. 2. Gardens--Japan--Design--History. I. Title. SB458.M36 2012 712.0952--dc23 2011019342 Distributed by North America, Latin America & Europe Tuttle Publishing, 364 Innovation Drive North Clarendon, VT 05759-9436 USA Tel: 1 (802) 773-8930; Fax: 1 (802) 773-6993 [email protected]; www.tuttlepublishing.com Japan Tuttle Publishing, Yaekari Building, 3rd Floor 5-4-12 Osaki, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 141-0032 Tel: (81) 3 5437-0171, Fax: (81) 3 5437-0755 [email protected], www.tuttle.co.jp Asia Pacific Berkeley Books Pte. Ltd. 61 Tai Seng Avenue, #02-12, Singapore 534167 Tel: (65) 6280-1330, Fax: (65) 6280-6290 [email protected]; www.periplus.com 15 14 13 12 1111EP 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in Hong Kong TUTTLE PUBLISHING® is a registered trademark of Tuttle Publishing, a division of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. contents 6 Preface chapter 1 A Sense of Nature 8 Introduction 14 Shinjuku Gyoen 20 Koishikawa Shokubutsu-en 24 Gardens of Ohara 30 Kaku-ji Temple 34 Murin-an chapter 2 The Modular Garden 38 Introduction 44 Chishaku-in 48 Ryutan-ji Garden 52 Toji-in 56 Kodai-ji Garden 60 Sekizo-ji chapter 3 Landscape Gardens 64 Introduction 70 Sengan-en 74 Koraku-en 78 Shuizen-ji Joju-en 82 Ritsurin-koen 86 Rikugi-en chapter 4 Requisitioning Space 90 Introduction 96 Kyu Shiba-Rikyu Onshi Garden 100Koishikawa Koraku-en 104Genkyu-en 108Canadian Embassy Garden 112Kiyosumi-teien chapter 5 Healing Gardens 116Introduction 122Mukojima Hyakka-en 126Zuisen-ji Garden 130Nezu Museum Garden 134Isui-en 138Shikina-en 142Bibliography 142Historical Periods 143Glossary 144Acknowledgments PREFACE Garden nature, like human nature, requires care and nurturing if it is not to lead to a kind of inanition. Pondering the fate of the Japanese garden, the Meiji era writer Lafcadio Hearn wrote: “These are the gardens of the past. The future will know them only as dreams, creations of a forgotten art.” In this respect, thankfully, he was wrong. How is it possible, though, to enjoy peace and tranquility, to savor Japanese gardens as healing, regenerative spaces when they have become so popular? Victims of their own success, whatever mystic or higher qualities they once had are at risk of being drowned out by the din of over-patronage. Japanese master gardens, however, may still offer alternative models for environmental enhancement. The purifying sensation one experiences on entering a garden affirms its power to promote a healthy emotional and spiritual life. In mirroring our yearning for stability and peace, our search for a settled place, its paths return us to our original nature. In exploring the garden, we are making renewed contact with Japanese culture. Once we have understood one form, we may more readily appreciate another. In appropriating differing elements of Japanese culture, the Japanese garden prepares us for an examination of other arts and practices. Japanese aesthetics, the fine-tuning of taste, the development of connoisseurship through the appreciation of beauty, came later than the proto-gardens of the pre-Shinto era, but the transition from divine nature to art was relatively seamless. And yet, the revisualization of nature that takes place through the filtration of art in the Japanese garden is often quite different from what we are accustomed to. Disarmed, for example, by the vision of compositions purporting to be landscape works but made entirely of stone and gravel, we are forced to reconsider the place of nature in the garden, where appearances can be deceptive. The painter David Hockney, whose photomontages of the Ryoanji garden in Kyoto are playful reinterpretations of time and space, recognized this when he wrote: “Surface is an illusion, but so is depth.” As a photographer, I am forced to view and analyze the Japanese garden through a lens. While shying away from discussing the variations in approach between Japanese and Western photographers, there do appear to be differences in the way their garden books are illustrated. It may be a case of suggestion and

Description: