James Boswell PDF

Preview James Boswell

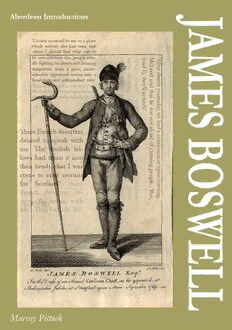

J Aberdeen Introductions A ‘Corsica occurred to me as a place which nobody else had seen, and where I should find what was to M be seen nowhere else, people actu- ‘dtehsrieratsfl‘weeeChillodlsh deoyFeueim rc,firr shraipsgistbc eenehhoalloonietv nip boe ngclosocges chpd afpaufpyno rcr reddeortrel ue mslaseiiadesbnkl s ehledtydaea ore tdfi prywnm psge taaehoneentietoid tndroiarneh ssnn,nfg oo at iif wr nnospmchttrlooaa ielnt cnriebgeea-’ ’of cunning people...’But, (saupon cunning. McLeod said tAfter dinner yesterday, we (said I), they’ll scratch’McLeod said that he was not afraid‘After dinner yesterday, we had a co ES B mltcfFsohoiorrweereme .ind sre c TSh hhtcteah ooodae ddt rltesaasfa,sni opksetdoeeerh’at nla eikr stre ihst‘cIt rwhiwunfdrieiettaetlohess-- id I), they’ll scratchhat he was not afraidhad a conversation of cunning people...’Butnversation upon cunning OS ’ , . me. The foolish fel- W E L L Murray Pittock JAMES BOSWELL Murray Pittock Aberdeen IntroductIons to IrIsh And scottIsh culture AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies University of Aberdeen ©Murray Pittock First published (paperback) in 2007 by AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies 19 College Bounds University of Aberdeen AB24 3UG This electronic edition published in 2015 by Aberdeen University Press 19 College Bounds University of Aberdeen AB24 3UG ISBN 978-1-85752-030-9 (pdf ebook) This title is also available in the following format: ISBN 978-1-906108-01-4 www.abdn.ac.uk/aup A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library The right of Murray Pittock to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 To Alexander Broadie Contents Acknowledgements vii Introduction On Biographers and Biografiends 1 Chapter One Boswell’s Life and the Life of the Mind 9 Chapter Two Self and Other in the Art of Boswell 31 Chapter Three Fratriotism: Boswell, Corsica, Ireland and America 43 Chapter Four Was Boswell a Jacobite? 69 Chapter Five Boswell and Belief 81 Chapter Six Boswell’s Li(f)e? Making Johnson Up 95 Notes 113 Bibliography 119 Acknowledgements The influences on the making of this book were many and varied: it is a part of a more extended research project on Boswell’s Political Correspondence in the Yale editions which has been going on for a number of years. My first thanks are due to Claude Rawson, the Bodman Professor of English at Yale, who first approached me with a view to working on the Yale editions; and to Gordon Turnbull, who as General Editor of the Yale Boswell, enabled me to hold a visiting fellowship at Yale in 1998 and 2000-1. Some of the ideas of this book were first worked out at Yale; others formed the subject of seminar and conference papers in Edinburgh, Oxford and elsewhere. I am grateful to the good offices of the librarians at the Beinecke, the Bodleian Library, the National Library of Scotland and the John Rylands Library for their support in the research that helped to make this book possible: and to Sheriff Neil Gow for the invitation to preside over the Boswell Society in 2001, and to attend the re-opening of Auchinleck House that year by the Landmark Trust. It has been a great pleasure to have been able to discuss Boswell and eighteenth-century Scotland over the years with so many scholars, and to have learnt from the writing and addresses of others. In particular my thanks are due to Tom Crawford, whom I have had the privilege of knowing for over thirty years, and whose outstanding scholarship still does not always receive its due; to Ken Simpson, my colleague at Strathclyde from 1996 to 2003; to James Caudle at Yale; and most sig- nificantly to Alexander Broadie, to whom this book is dedicated in trib- ute to the many evenings we have spent putting the long-dead world of eighteenth-century Scotland to rights. The loyalty of the Faculty of Advocates to one of their famous, if wayward, sons should also be noted, in particular the contribution of Angus Stewart QC, for many years Librarian of the Faculty. As ever, the conversations I have been able to have with my wife, Anne, are the seedbed of many ideas which are found not only in these pages, which will in the chapters that follow provide an interpretation of Boswell as an artist and a Scottish thinker, together with an approach to the nature of that thought and art. For ease of reference, primary texts, particularly those by Boswell, will be mentioned by title in the text while important and frequently cited viii James Boswell secondary text will be referred to by author. Murray Pittock Glasgow, 2005 Introduction: On Biographers and Biografiends James Boswell (1740–95) is often held to be the first modern biogra- pher. This shorthand is indicative of the fact that he is often seen as the first to seek to document his subject, rather than relying on anecdote, tittle-tattle and memory; the first to present his subject in the manner of sympathetic centrality which is so much part of what we now see as the biographer’s art, and which renders it suspicious to some; and the first to use the autobiographical form of the diary to create an account of a third person, shifting the form of the epistolary novel from fiction to biography. Pepys reflects the subject; Boswell creates an object. There is much to be said for this view, even if it is not altogether accurate. As Donald Stauffer pointed out sixty years ago, while it was ‘the rise of the novel’ that ‘radically altered the art of English biography’, Boswell was not the first to benefit from that change. Boswell’s use of dialogue was anticipated by James Thomas Kirkman’s Memoirs of the Life of Charles Macklin (1779); his ethical seriousness in portraying Johnson and the minutiae of the supporting evidence adduced for that portrait were both anticipated by Johnson himself; and the revelation of charac- ter, one of Boswell’s crowning glories, was recommended by Johnson in a 1750 essay in the Rambler (no. 60). Boswell also wrote in opposition to already published and now seldom read lives of Johnson, particularly that of Sir John Hawkins. A tradition of spiritual autobiography under- pins even that marvel of Boswell’s self-revelatory art, his Journal. Yet whatever the influence of novel, stage, spiritual self-revelation, ethical seriousness, the stress on detail, the anticipatory role of the novel or of travel literature, in some sense Boswell, both in his Journal and his Life of Johnson, surpassed them all in creating an imaginative approximation to the cultural performance of eighteenth-century mental and social life, which nonetheless became, despite Johnson’s stress on ‘absolute truth’ in biography, a myth: Boswell’s myth of Johnson and of himself.1 It is this creative representation of reality which renders the very modern biography which is held to be Boswell’s central achievement both popular and suspect. The stark exemplars of Plutarch, the tidbits of Suetonius or Aubrey, the judgement of achievement in Johnson’s own Lives of the Poets, all in their turn give way to an intimacy which com-