Is Israel Apartheid?: Reporting the Facts on Israel and South Africa PDF

Preview Is Israel Apartheid?: Reporting the Facts on Israel and South Africa

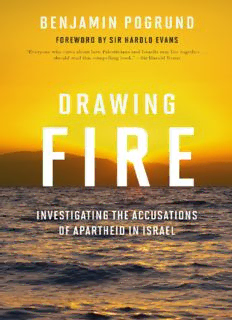

Additional Praise for Drawing Fire ‘While many label Israel “an apartheid state”, Benjamin Pogrund actually experienced apartheid, from Sharpeville to Mandela’s liberation. He is therefore well placed to dissect the easy analogy between Zionist Israel and apartheid South Africa. This critical and detailed account of the complexity of Israel’s situation will not please some, but it will be an eye-opener for many who have hitherto accepted the conventional wisdom. For those who do not think in monochrome, this is an important book.’ —Colin Shindler, Pears Senior Research Fellow in Israel Studies, SOAS, University of London Drawing Fire BY THE SAME AUTHOR Robert Sobukwe: How Can Man Die Better Nelson Mandela War of Words: Memoir of a South African Journalist Shared Histories: A Palestinian-Israeli Dialogue (coeditor) Drawing Fire Investigating the Accusations of Apartheid in Israel Benjamin Pogrund ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com 16 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BT, United Kingdom Copyright © 2014 by Rowman & Littlefield All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pogrund, Benjamin, author. Drawing fire : investigating the accusations of apartheid in Israel / Benjamin Pogrund. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-2683-8 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-1-4422-2684-5 (electronic) 1. National characteristics, Israeli—Political aspects. 2. Israel—Social conditions—21st century. 3. Israel—Politics and government—1993– 4. Israel—Ethnic relations. 5. Zionism. 6. Apartheid. 7. Human rights—Israel. 8. Human rights—South Africa. 9. Palestinian Arabs—Government policy—Israel. 10. Arab-Israeli conflict—Influence. I. Title. DS119.76.P64 2014 956.9405'4--dc23 2014006848 TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America For my parents, Bertha and Nathan Pogrund, who gave me life, and for Anne, who shares it with me Foreword Is Israel an apartheid state? There is nobody to trust more for a dispassionate, informed answer than Benjamin Pogrund. He has unique experience. He has lived the question as a victim of apartheid for twenty-six years of valiant reporting in South Africa and more than fifteen years as an Israeli citizen in Jerusalem, deeply sympathetic to Palestinians under occupation. In Israel, he founded the Yakar Centre for Social Concern in 1997, which was dedicated to fostering dialogue between Jews and Jews, Jews and Muslims, Jews and Christians, and Palestinians and Israelis. In South Africa, he was jailed and persecuted as an enemy of the state and for five years denied a passport. His crime was to recognise and objectively report the lives of blacks under apartheid, the cruelties inflicted on the leaders, and the seeds of the political aspirations that finally led to freedom. The mainstream press was not doing that. The townships were off limits. His brave newspaper, the Rand Daily Mail, was critical of the policies of apartheid, and its owners yielded to government pressure and shut it down in 1985. But it was the scrupulously accurate reporting by Pogrund, of torture in the prisons among much else, that most enraged the Afrikaner government (and eventually stirred world opinion), and it was the honest competence of this straight journalism that impressed the nascent black leadership. Here was a white Jewish reporter prepared to risk his neck to find and reveal what was happening – favourable or not to their movement – and whatever the pressure never reveal his sources. It was a stand for which the government put him in prison, and persecuted and investigated him as a threat to national security. It was also a stand that won Pogrund the trust of the African resistance, in particular, Nelson Mandela and Robert Sobukwe. Pogrund was the first non-family guest in twenty years welcomed in prison by Nelson Mandela. He became a biographer of both Mandela and Sobukwe, and in the later years continued speaking for them. He found it hard to write this book. It had to be hard because when you know both scenes so well, and don’t come loaded with preconceptions, you have to think and find the right words. That’s an exercise in cognition and judgment unknown to the grandiose ideologues and unthinking boycotters prominent on the Left in Europe, and fringe academics and credulous students whose vehemence in indicting Israel as an apartheid state is matched only by the depths of their ignorance of both societies. Far easier for the glib to purloin the odium of ‘apartheid’ than painstakingly to assemble evidence for the indictment and assess it judiciously, sparing no one. Look how Pogrund sets the scene: Each of the two main competing groups, Jews and Arabs, has right on its side, through history, land, religion, geography and tradition. The dilemma is how to satisfy their separate demands and aspirations to a tiny piece of land. The problem is bedevilled because in the long struggle between them, neither side has always behaved well, inflicting death and destruction on the other. He empathises with Jewish fears about annihilation, and he empathizes with Palestinian cries for freedom. He believes in Israel’s right to exist but thinks occupation is wrong. I know the anguish of his ambivalence, but also the determination he brings to resolving the dilemmas. He tracks the history of Israel since its founding, the displacement of Palestinians, the Arab invasions, the intifada, the incursions of the settlers, the attempts to achieve the two-state solution he supports, and the war of extermination by Hamas, who pledged never to recognise Israel. He has compiled an incisive comparative tabulation of all the civil society discriminations against Arabs in Israel and whites against blacks in apartheid South Africa. There is no comparison. The apartheid propagandists stand as vainly naked as the fairy tale emperor admiring his gorgeous raiment. This is not because Israel is without sin, but because the anti-Semitic mob never lets a certainty stand in the way of a slogan. Forget the democratic practices of Israel, its elections and higher education open to all, its free and highly critical press, its independent judiciary, its equal welfare benefits and medical treatments caring for Jew and Arab. Close an eye to all the oppressions of the Arab states surrounding Israel, the suicide bombings by the jihadists glorified by the Palestinian Authority, which poisons the minds of children in its schools and viewers of its television programs. Why do the apartheid propagandists ignore, and thereby implicitly condone, the human rights abuses of others? Why do the United States and Europe continue to finance the odious ‘education’ programs of the Palestinian Authority that expunge Israel from the map? One hears Yeats again: ‘The best lack all conviction while the worst are full of passionate intensity’. Pogrund is gentle in his assessment of the most credible of the campaigners for a boycott of Israel, Archbishop Tutu. How is it, one may ask, that this good man became associated with apartheid defamers? The sad answer is that while he was an inspiring leader in South Africa, he knows too little about Israel. Pogrund has conversed with Tutu. He corrects his factual errors on discrimination in Israel. The archbishop means well, but he is close to selective sanctimony when he says he supports Israel’s right to exist while lending his good name to people who would like to see every Jew dead. Pogrund, by contrast, roundly exposes the liars and hypocrites among the committed enemies of Israel – but he is unflinching in his criticisms of Israel. He condemns the occupation of the West Bank ‘with all the consequent injustice, harshness and cruelty together with the creeping settlement of Jews in the territory and East Jerusalem, plus its siege of the Gaza Strip’. The blindly arrogant settlers and their right-wing supporters are ‘guilty of colonialism, a crime in international law’. They must be checked in discrimination against Palestinians, he says, or they will deserve the apartheid label with consequences grave beyond measure for Israel. The boycott of Israel called for by the apartheid campaigners provides a cheap moral thrill, but it intensifies the fears of Israelis, driving them to the Right, and it does nothing for the Palestinians whose livelihoods are tied to the innovative Israel. The Left’s case for boycotts is that sanctions freed South Africa. It is questionable. The opposite has been argued – that industrial sanctions increased the society’s reliance on the conservative agricultural sector, the core of what became the Afrikaner Volksfront of extremist separatist groups. Pogrund’s view is that apartheid collapsed in South Africa ‘when it became clear to those whites in power that it was not in their own self-interest to perpetuate by force what was clearly an unjust system of oppression, and when black leaders extended the hand of reconciliation to their former oppressors’. He is too modest to underline his part in that. Pogrund’s years and years of reporting of the human rights abuses were surely central to the gradual disaffection with apartheid among decent South African whites and governments worldwide, but especially the US Congress. An opinion formed into a conviction: apartheid could not be tolerated any longer. I have known Pogrund and his work for forty years. As, successively, editor of the Sunday Times of London and the Times, and editorial director of US News and World Report, I came to admire more and more his courage and judgment in reporting for us from South Africa, as I now applaud him for the intellectual integrity that has enabled him to distil what he learned in both the incipient black nation of South Africa and the embattled nation state of Israel. Everyone who cares about how Palestinians and Israelis may live together in the same neighbourhood in freedom and without fear should read this compelling book, but especially the genuine idealists worldwide among the apartheid campaigners. Amid the detritus of the propagandists, the dedication to truth of Benjamin Pogrund, reporter, is morally exhilarating. Sir Harold Evans former editor of the Sunday Times and the Times author of The American Century and My Paper Chase Preface Living in apartheid South Africa was easy in moral terms. Living in Israel is difficult. In apartheid South Africa the choice was clear and beyond escape: it was good versus evil. Apartheid was the Afrikaans word for apartness, which meant racial segregation and discrimination enforced by the white minority on the country’s black, coloured and Asian peoples. It was wrong and inhuman, denying freedom and stunting and destroying lives. The problem for concerned people was not merely to do the obvious thing and reject apartheid, but to decide what to do about it. That is, how far to go in opposing it against an increasingly tyrannous government: from being a passive bystander to imperilling your liberty, even your life. In Israel, the moral choices are many and complex and are a daily challenge. Each of the two main competing groups, Jews and Arabs, has right on its side, through history, land, religion, geography and tradition. The dilemma is how to satisfy their separate demands and aspirations to a tiny piece of land. The problem is bedevilled because in the long struggle between them, neither side has always behaved well, inflicting death and destruction on the other. Each side believes that it is in the right, and each side fears and rejects the other. Jews and Arabs are a mirror image of each other: each believes that force is the only language that the other understands; each believes that the other is trying to wipe it out. That there is some truth in these beliefs on both sides adds to the complexities. I straddle both apartheid South Africa and today’s Israel – not merely by having lived in both countries, but because I have been immersed in the problems and conflicts of each and in search for solutions. I was born in Cape Town and before the age of ten was taking part in Habonim (The Builders), a Jewish socialist youth movement. As a teenager I held leadership positions. In May 1948, as a fifteen-year-old, I was in the Habonim group which performed folk dances at the Jewish celebration in Cape Town of the creation of the State of Israel. I grew up steeped in belief in Zionism as a beautiful and pure creed of Jewish emancipation after centuries of persecution. I was emotionally filled with awareness of my Jewishness: with the knowledge that the aunts and uncles and cousins whom my parents had left behind in Lithuania in the villages of Abel and Dusadt when they emigrated to South Africa in the 1920s had been murdered by the Nazis on 25 August 1941. The report of the SS Einsatzgruppen – Action Groups – signed by Jager, SS-Standardartenfuhrer, on 1 December 1941, recorded the killing of ‘112 Jews, 627 Jewesses, 421 Jewish children’ in Obeliai (Abel). It said: ‘In Lithuania there are no more Jews, apart from Jewish workers and their families. The distance between from [sic] the assembly point to the graves was on average 4 to 5km’. Also in May 1948, I was politically interested enough as a high school pupil to go