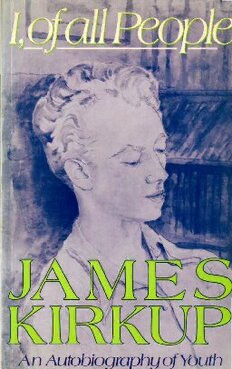

I, of All People PDF

Preview I, of All People

An Autobiography of Youth SELECTED WORKS Of JAMES KIRKUP The Submerged Village A Correct Compassion A Spring Journey The Descent into the Cave The Prodigal Son Refusal to Conform A Bewick Bestiary Zen Gardens (photo-etchings by Birgit Skiold) Paper Windows: Poems from Japan White Shadows, Black Shadows: Poems of Peace and War The Body Servant: Poems of Exile Scenes from Sesshu (photo-etchings by Birgit Skiold) To the Ancestral North: Poems for an Autobiography Cold Mountain Poems Scenes from Sutcliffe (portfolio of poems and photographs) The Tao of Water (photo-etchings by Birgit Skiold) Miniature Masterpieces by Yasunari Kawabata Insect Summer (children's novel) The Magic Drum (children's novel) The Love of Others The Only Child: An Autobiography of Infancy Sorrows, Passions & Alarms: An Autobiography of Childhood These Horned Islands: A Journal ofJ apan Tropic Temper: A Memoir of Malaya Filipinescas Streets of Asia No More Hiroshimas: Poems & Translations Selected Poems of Takagi Kyozo Modern Japanese Poetry Zen Contemplations The Guitar Player of Zuiganji Dengonban Messages: One-Line Poems Ecce Homo - My Pasolini: Poems & Translations Fellow Feelings The Sense of the Visit: New Poems JAMES KIRKUP I, of all People 1 An Autobiography of Youth WEIDENFELD AND NICOLSON LONDON Copyright © James Kirkup 1988 This paperback edition published in 1990 First published in Great Britain in 1988 by George Weidenfeld & Nicolson Limited 91 Clapham High Street, London sw4 7TA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN O 297 79569 4 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd, Frome and London In memory of YAMAGUCHI T AKEYOSHI O que nos vemos das cousas as cousas. Por que veriamos nos uma cousa se houvesse outra? Por que e que ver e ouvir seria iludirmo-nos Se ver e ouvir sao ver e ouvir? O essencial e saber ver. Saber ver sem estar a pensar. Saber ver quando se ve, E nem pensar quando se ve Nern ver quando se pensa .... What we see of things are things themselves. Why should we see a certain thing if something else were there? Why should seeing and hearing be self-delusion If seeing and hearing are seeing and hearing? The essence is to know how to see. To know how to see without thinking we see. To know how to see when we are seeing, And not to be thinking when we are seeing Not to be seeing when we are thinking. FERNANDO PESSOA From O Guardado, de Rebanhos/translated from the Portuguese by James Kirkup Live all you can; it's a mistake not to. It doesn't so much matter what you do in particular, so long as you have your life. If you havn't had that what have you had? HENRY JAMES From The Ambassadors Contents Acknowledgements Xl Prologue Xlll PART ONE: PRE-WAR A Grave of Academe 1936-8 3 First Steps Abroad 1938---9 15 Summer in the Alps 1939 36 PART TWO: WAR A Poet at War 1940 45 One Day in the Middle of a War 1940-3 59 Strange Tenant 1943 69 A Labourer Unworthy of his Hire 1943 75 Forest and Farm 1943-5 88 A Day on the Thresher 1945 IOI Towards Hiroshima and Nagasaki 1945--6 IO) PART THREE: POST-WAR Peacetime Fighter 1946-7 II5 A Post-War Outsider 1947-8 134 'I, of all People' 1948 144 The Poets' Other Corner 1948 157 Hell is a City 1948 165 'I'll Turn it All to Poetry' 1948 174 PART FOUR: PRE-ORIENTATIONS Dear Old Joe 1948-55 187 Unfellowly Fellowships 195o--6 208 Epilogue 241 Index 253 ix Acknowledgements Parts of this book have appeared in The London Magazine, Peace News, The South Shields Gazette and Shipping Telegraph, Eigokyoiku (Tokyo), The Listener, The Times Literary Supplement and The Britishness of the British (Seibido Publishing Company, Ltd, Tokyo). l I am grateful to the editors and publishers for permission to reproduce material here. The quotations preceding each part of the text are taken from W. H. Auden's poem No.II in Some Poems (Faber and Faber). XI Prologue in Retrospect Tightrope and Seesaw: The Makings of a Poet In those magic days of my childhood, in the twenties and the early thirties, large, boisterous families were common in working-class districts of Britain, especially among the Roman Catholics, whose religion commanded them to 'be fruitful and· multiply', and in families of Irish, Arab, Inillian and Chinese immigrants, most of whom had come to England as British citizens from the colonies we then still held in S.E. Asia, India and Africa. By contrast, our own little family of mother, father and only son was therefore unique in our working-class street, and something ofan anomaly, because though we were definitely working-class, socialists, 'the salt of the earth' and proud of it, having only one child was somehow construed as a sign of middle-class superiority, and my mother and father were the last persons in the world to put on airs of superiority, to pretend to be what they were not - as some working-class people with social ambitions did. All the other families in our street had at least two children, often three, four or five, and sometimes even six or seven children had to share a three room flat with their parents and grandparents. I can remember two families who had ten children, all living together in four small rooms: in summer, during fine nights, they used to sleep on mats in the back yard - to me a very romantic thing to do, but I was never allowed to do so. The gypsy in me wanted to get away from the care and comfort of the home and the parents I loved with undivided devotion. So the neighbours often used to call the Kirkup family, with Geordie wit and affection, 'The Holy Family'. This is a good example of the inventive and sometimes caustic humour ofTynesiders, which has a touch of salty bitterness in it from the sands and the sea, but is always based on certain humble truths. It is a deflating but not damaging sense of the ridiculous, and is used with consummate skill to puncture any delusions of grandeur in fellow-Geordies, or to deride any mistaken notions we might have about our own importance. It is really a very healthy humour, that helps us to see one another - and ourselves - as we really are, in the unsparing but desirably welcome light of prosaic reality. I would call it a xiii PROLOGUE IN RETROSPECT mordant sense of wholesome mockery and affectionate fun. But as a child, I was very shy and sensitive, and took everything people told me for the truth: so my fragile innocence was often shattered by Geordie down-to earth witticisms and carefully chosen insults. For this reason, I think, I am still frightened of my fellow countrymen: their ironies are too painful to bear, especially after living so long in Japan. The British have lost some of their affectionate sense of fun, and have turned self-destructive, always complaining and back-biting and trying their best to pull other people down, to destroy whatever comforting illusions they have left after years of war and unemployment and racial strife. Writers and poets in Britain today are particularly vicious in their attacks on one another: one finds none of the fellowship and solidarity among all kinds of writers that I have enjoyed in Europe, America and Japan. Perhaps this is the reason why modern British poetry is now such a boring mess of domestic and academic conflicts, without a trace of originality or curiosity about other literatures: it is insular and pedantic and terribly provincial, and I despair of ever persuading my fellow British authors to try to see the world around us as I see it - with an open, internationalist mind. Anyhow, I soon became aware of the fact that the Kirkups of Ada Street were known as 'The Holy Family'. It seemed to set us apart. My mother's name was Mary, and my aunt's name was Anna, and though my father was not called Joseph, the suggestion was inescapable-and quite acceptable to my child's mind - that I was the boy Jesus. And after all, had not Joseph been a carpenter, like my own father? 'The Holy Family' was not a bad nickname for the three of us. It did not at all surprise or alarm me to be thought of as Jesus Christ come back to earth in the form of a carpenter's son. As a child, I suffered from anaemia, and my skin was so pale, almost translucently white, and my pallor would increase to dead white whenever I was up beyond my usual early bedtime, or when I was extremely tired. At such times, I would look as frail and insubstantial as a ghost, so I was also sometimes called 'The Holy Ghost' by the young, tough lads in our back lane. They were rosy-cheeked, vigorous and full oflusty life. No one would ever have thought of comparing them with Jesus. But I was not as they were. I was so quiet and pale, with hair ash-blond almost to the point of whiteness, and my big, dark blue eyes were deep, mysterious pools in thick, blond lashes. In some ways, too, I was unnaturally wise: not for nothing had my Granny Johnson called me 'a wise bairn'. My father agreed with her, saying that my intelligence came from the Kirkup, Earl and Falconer side of the xiv