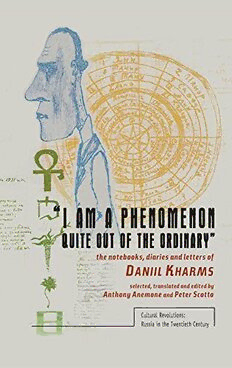

Table Of ContentThe Notebooks, Diaries, and Letters of

DANIIL KHARMS

Cultural Revolutions: Russia in the Twentieth Century

Editorial Board:

Anthony Anemone (The New School)

Robert Bird (The University of Chicago)

Eliot Borenstein (New York University)

Angela Brintlinger (The Ohio State University)

Karen Evans-Romaine (Ohio University)

Jochen Hellbeck (Rutgers University)

Lilya Kaganovsky (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign)

Christina Kiaer (Northwestern University)

Alaina Lemon (University of Michigan)

Simon Morrison (Princeton University)

Eric Naiman (University of California, Berkeley)

Joan Neuberger (University of Texas, Austin)

Ludmila Parts (McGill University)

Ethan Pollock (Brown University)

Cathy Popkin (Columbia University)

Stephanie Sandler (Harvard University)

Boris Wolfson (Amherst College), Series Editor

The Notebooks, Diaries, and Letters of

DANIIL KHARMS

Selected, Translated and Edited

by Anthony Anemone and Peter Scotto

Boston

2013

The publication of this book is supported by the Mikhail Prokhorov Foundation

(translation program TRANSCRIPT).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

A catalog record for this title is available from the Library of Congress.

Copyright 2013 Academic Studies Press

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-936235-96-4 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-61811-146-3 (electronic)

Cover design by Sasha Pyle

Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013

28 Montfern Avenue

Brighton, MA 02135, USA

[email protected]

www.academicstudiespress.com

For our fathers.

“Translations that are more than transmissions of subject

matter come into being when in the course of its survival

a work has reached the age of its fame.”

−Walter Benjamin

Contents

Acknowledgements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

About this translation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Preliminaries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

1924–1925 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

1926 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

1927 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .115

1928 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 158

1929 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 220

1930 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 242

1931 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 260

Arrest by OGPU. December 1931 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 291

1932 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 301

Diary 1932-1933 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 336

1933 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 352

1934 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 428

1935 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 451

1936 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 463

The Blue Notebook . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 477

1937 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 485

1938 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 497

1939 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 500

1940 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 502

1941 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 516

Unknown years . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 517

Epilogue and Finale . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 521

Chronology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 535

Selected Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 541

Commentary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 543

Glossary of Names, Places, Institutions and Concepts . . . . . . . 565

Acknowledgements

E

very work of scholarship rests on the work of others in the fi eld. What

we have done here would not have been possible without the dedication

and hard work of those scholars who rescued Kharms and his artistic

legacy from decades of oblivion. When Mikhail Meilakh, Vladimir Earl,

Aleksandr Aleksandrov, and Vladimir Glotser started studying Kharms’s life

and work in the late 1960s, he was almost completely unknown. Thanks to

their multiple editions, scholarly articles, and books, today Kharms’s works

are acknowledged classics of twentieth-century Russian literature. Another

generation of Russian scholars and researchers, including Aleksandr

Kobrinsky, Andrei Ustinov, Aleksei Dmitrenko, Anna Gerasimova, Andrei

Krusanov, Evgenia Stroganova, and Valery Shubinsky, has continued the

recovery of Kharms, contributing immeasurably to our understanding of his

life and work, and maintaining the high standards set by their predecessors.

We owe a special debt of gratitude to Valery Sazhin of the Russian

National Library in Saint Petersburg and Jean-Phillipe Jaccard of the

University of Geneva for their invaluable publication of the full corpus of

Kharms’s notebooks and diaries in Russian.

We would also like to thank: Andrei Ustinov for his meticulous reading

and constructive criticism of a long and complicated manuscript and his

generous sharing of photographs from his private collection; Dr. Gabriel

Griffi n for help identifying some of Kharms’s maladies, imagined or

otherwise; Eugene Hill of Mount Holyoke College for his encouragement

and careful reading of early drafts of this work; Bella Ginzbursky Blum

of The College of William and Mary, Boris Wolfson of Amherst College

for their helping untangle some especially tricky passages in the Russian;

F. F. Morton of South Hadley for his gentle instruction in the art of translation;

Marietta Turian of Saint Petersburg for her support and inspiration over the

years; Mikhail Vorobyov of Saint Petersburg for sharing family memories

and photographs of some of the people in this book; Anaida Bestavashvili

and Vladimir Livshits of Moscow for their enthusiasm and support of the

project; Dmitry Sokolenko of Saint Petersburg for his enthusiasm for all

7

AAcckknnoowwlleeddggeemmeennttss

things OBERIU; Susan Downing for her help compiling the Glossary;

Stanley Rabinowitz, director of the Amherst College Center for Russian

Culture, for allowing us access to rare items in the ACRC collection; Mike

Blum of the College of William and Mary, for (always) much-needed

technical assistance; Alexandra Pyle for her cover design; Val Vinokur of

the New School for good advice and even better friendship; Robert Pyle,

Elisabeth Pyle, and Robinson Pyle for their help explaining the fi ner points

of mathematics and music; Shoshana Lucich and Michaela Beals of Stanford

University for last-minute research assistance; and our editor at Academic

Studies Press, Sharona Vedol.

We are also grateful to Mount Holyoke College for a 2011-2012

sabbatical award; to the Mount Holyoke Faculty Grants Committee for

providing material support for this research; to the New School for Public

Engagement for supporting this research with a sabbatical award in 2011-

1012; to the Interlibrary Loan Departments at Mount Holyoke College, the

New School, and Bobst Library of New York University.

Finally, we would like to thank our patient and long-suffering mothers,

without whom none of this would have been possible.

Last, and most of all, we thank Vivian Pyle and Amy Gershenfeld

Donnella for their unfl agging love and unfailing support.

A.A. and P.S.

Introduction

O

n February 2, 1942, Daniil Kharms died in the psychiatric section of

an NKVD prison hospital in Leningrad. He was barely 36 at the time,

a year or so younger than Aleksandr Pushkin was when he had died

105 years earlier, almost to the day, of a gunshot wound to the stomach in a

better part of town.1 Given the desperate conditions in Leningrad during the

fi rst winter of what would drag on to be a 900-day siege by the Wehrmacht,

it is assumed that as the city slowly starved to death around him, Kharms

did too. Like Pushkin, Kharms got it in the stomach.

During his lifetime, Kharms was known as a failed avant-garde poet

and dramatist who had some notable, if brief, success writing poems and

stories for children. However, for more than two decades following his

death, his name and his works were consigned to an enforced oblivion.

Today, after a heroic recovery operation mounted by dedicated friends,

family members, scholars, and critics over the course of decades, he is read

and remembered as a major voice of twentieth-century Russian literature.

Russians now know Kharms not only as the author of classic children’s

verse, but also as a central fi gure in a vibrant post-revolutionary avant-

garde that was the contemporary of Dada and surrealism and anticipated

the “Theater of the Absurd”; as the author of poems that built upon the

linguistic innovations of Russian Futurism; as the creator of a genre of mini-

stories beneath whose disjointed and darkly comic surfaces the violence of

the Stalinist world shimmers; as one more victim of a state whose tolerance

for deviation of any kind was strictly limited, and whose carnivorous

appetite is only too well-known. His posthumous glory is such that editions

of his works, both scholarly and popular, have been published in print runs

numbering into the thousands and tens of thousands2 and, with the advent of

the internet, there are now dozens of websites dedicated to preserving and

promulgating his legacy.

Kharms’s recovery is all the more remarkable when one considers

that during his lifetime, he managed to publish only two of his works “for

adults.”3 The rest had to wait for better days.

9