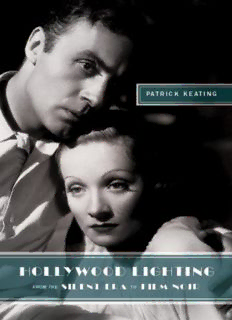

Hollywood Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film Noir PDF

Preview Hollywood Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film Noir

Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film Noir Film and Culture/John Belton, General Editor Patrick Keating Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film Noir Columbia University Press New York Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex E-ISBN 978-0-231-52020-1 Copyright © 2010 Columbia University Press All rights reserved cup.columbia.edu The author and Columbia University Press gratefully acknowledge the support of two grants from the Trinity University Department of Academic Affairs and the University Department of Communication in the publication of this book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Keating, Patrick, 1970– Hollywood lighting from the silent era to film noir / Patrick Keating. p. c.m Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-231-14902-0 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-231-14903-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-231-52020-1 (ebook) 1. Cinematography—Lighting. 2. Hollywood (Los Angeles, Calif.)—History 1. Title. 2009015406 A Columbia University Press E-book. CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at cup- [email protected]. References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared. For my mother Contents Acknowledgments Introduction: The Rhetoric of Light Part I: Lighting in the Silent Period 1 Mechanics or Artists? 2 From the Portrait to the Close-Up 3 The Drama of Light 4 Organizing the Image Part II: Classical Hollywood Lighting 5 Inventing the Observer 6 Conventions and Functions 7 The Art of Balance Part III: Shifting Patterns of Shadow 8 The Promises and Problems of Technicolor 9 The Flow of the River 10 Film Noir and the Limits of Classicism Conclusion: Epilogue Notes Index Acknowledgments When I was young, my parents, Maria and Dennis, bought me a VHS tape of The Third Man. Little did they know that I would watch the film repeatedly, subjecting the entire family, including my sisters, Coleen and Amy, to hours and hours of zither music. It wasn’t the zither music that fascinated me—it was the cinematography. Without my family’s patience and support, I never would have learned to love the art of lighting, and this book would not exist. When I went to college, I already knew that I wanted to study film. Once at Yale, taking challenging, thought-provoking classes with Scott Bukatman, David Rodowick, and Angela Dalle Vacche, I began to think of film as a socially significant form of cultural expression. After graduating, I returned to my native Los Angeles and earned an M.F.A. in film production from the University of Southern California. USC gave me the opportunity to get behind the camera and study cinematography directly, under the guidance of cinematographers Woody Omens and Judy Irola. My thinking about film was further shaped by Ivan Passer, Bruce Block, and Rick Jewell. I also collaborated with several talented peers, including Jordan Hoffman, Dionne Bennett, Camille Landau, Michael Friedrich, Wei-shan Noel Yang, Benjamin Friedman, Mark Skoner, Chris Komives, and (outside USC) Daria Martin. This book is based on the dissertation I wrote while at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. I had the ideal advisor for the project, David Bordwell, whose thorough knowledge of Hollywood film history is matched by his infectious enthusiasm for the art of film. David’s work is a constant reminder that film studies can be both intellectually ambitious and enjoyable. I feel special gratitude toward Lea Jacobs and Vance Kepley, who nurtured this project in its early stages and served on my committee. Ben Singer shaped my thoughts about lighting in theater, painting, and photography. In addition, I was fortunate to be surrounded by great minds and great teachers, including Noël Carroll, Malcolm Turvey, Kristin Thompson, Ben Brewster, J. J. Murphy, Kelley Conway, Lester Hunt, and the late John Szarkowski. In my teaching career I have received warm support from several colleagues, and I want to thank in particular Jeff Smith, Scott Bukatman, Kristi McKim, Bill Christ, and Jarrod Atchison. I also consider it a privilege to have taught hundreds of smart, engaging students, who have taught me much about the cinema. I have discussed my ideas with many patient friends over the years. In addition to those already mentioned, I am grateful for the support of Vince Bohlinger, Jinhee Choi, Emily Cruse, Ben de Rubertis, Meraj Dhir, Lisa Dombrowski, Haden Guest, Warren Kim, Dara Matseoane- Peterssen, Mike Newman, Phil Sewell, Holly Willis, and Nancy Won. My family always reminds me that there is more to life than work—thanks, Kathleen, Mark, Aaron, Peter, Pat, Kristin, Hannah, Moira, Soren, and Isabella. It has been a joy to work with everyone at Columbia University Press, especially John Belton, Jennifer Crewe, and Kerri Sullivan. James Naremore and the anonymous reader provided careful and encouraging responses to my manuscript. They caught several errors, and made useful suggestions for improvement. Scott Higgins thoughtfully answered questions about studying Technicolor, and Tom Kemper helped me to improve the writing of several chapters. This project was supported by various grant awards from UW-Madison. An earlier version of the second chapter of this book, “From the Portrait to the Close-Up,” received the Society of Cinema and Media Studies student writing award and appeared in Cinema Journal. I developed related thoughts about Hollywood cinema in articles published in Aura and The Velvet Light Trap. At Trinity University, I received two grants to help me cover the printing cost of the many illustrations included herein— one from the Department of Academic Affairs, and another from the Department of Communication. Thank you. While living in Los Angeles and Madison, I took advantage of the local film culture, watching classic films in 35mm whenever possible. I saw many of the films discussed in this book on the big screen at UCLA and the UW Cinematheque, which offer superb film series every year. I conducted archival research at several institutions, watching Mary Pickford films and other silents at the George Eastman House; viewing several beautiful Technicolor films at the Academy Film Archive; studying both silent and color films at the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress; examining rare films at the UCLA Film and Television Archive; and watching Warner Bros. classics at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Television Research. In addition to film viewing, my research has drawn on documents housed in the USC–Warner Bros. Archive, the USC Cinematic Arts Library, the UCLA Performing Arts Special Collections, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Margaret Herrick Library, the Getty Research Institute, the New York Public Library, and the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Finally, my warmest thanks are given to Lisa Jasinski. Lisa supported this project in so many ways—with her sense of humor, her emotional encouragement, and her sharp editorial eye. She made this a better book, and she makes me a better person. Introduction: The Rhetoric of Light My opinion of a well-photographed film is one where you look at it, and come out, and forget that you’ve looked at a moving picture. You forget that you’ve seen any photography. Then you’ve succeeded. If they all come out talking about “Oh, that beautiful scenic thing here,” I think you’ve killed the picture. –Arthur C. Miller, in The Art of the Cinematographer Perhaps Arthur Miller did his job too well. Film is an art of light, but the art of Hollywood lighting remains so subtle that it usually escapes our attention. This is unfortunate, because Miller and his peers did much to shape our experience of the classical Hollywood cinema. Whether it is noticed or not, light can sharpen our attention, shift our expectations, and shape our emotions. In this study I propose to look closely at this art that was designed to go unseen and unnoticed. Three questions will guide this study. First, what were the major lighting conventions in the Hollywood of the studio era? All film scholars are familiar with Hollywood’s three-point lighting system, but this was only one of the countless techniques that constituted the art of Hollywood lighting. A richly detailed account of the various approaches to lighting should add greatly to our understanding of Hollywood cinema. Second, what functions did those different conventions perform? Even the most unobtrusive image can accomplish a range of tasks, from storytelling to glamour, from expressivity to realism. Third, how did the discourse of lighting shape these multifunctional conventions? The discourse of lighting is more than just a group of statements about arc lights and eye- lights—it is also a set of limitations on what can be said about technology and technique. These limitations made the use of certain lighting strategies seem inevitable, and others inconceivable. Convention, function, discourse—this study will explain the ways these three areas of cinematographic rhetoric are connected. We can think of a lighting convention as a recommendation about what to do given a certain cinematic context. When photographing a jail scene, consider

Description: