History of How the Spaniards Arrived in Peru (Relasçion de cómo los españoles entraron en el Peru), Dual-Language Edition PDF

Preview History of How the Spaniards Arrived in Peru (Relasçion de cómo los españoles entraron en el Peru), Dual-Language Edition

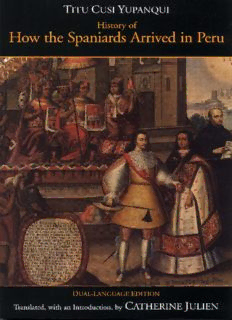

DQ -Blank 2/7/08 3:37 PM Page 1 History of How the Spaniards Arrived in Peru History of How the Spaniards Arrived in Peru Dual-Language Edition Titu Cusi Yupanqui Translated, with an Introduction, by Catherine Julien Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. Indianapolis/Cambridge Copyright © 2006 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. All rights reserved 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 For further information, please address: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. P.O. Box 44937 Indianapolis, IN 46244-0937 www.hackettpublishing.com Cover design by Abigail Coyle Text design by Meera Dash Composition by Agnew's, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yupangui, Diego de Castro, titu cussi, 16th cent. [Ynstruçion del ynga don Diego de Castro titu cussi Yupangui. English & Spanish] History of how the Spaniards arrived in Peru :dual-language edition / titu cusi Yupanqui ; translated, with an introduction, by Catherine Julien. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-10:0-87220-828-1 (pbk.) ISBN-10:0-87220-829-X (cloth) ISBN-13:978-0-87220-828-5 (pbk.) ISBN-13:978-0-87220-829-2 (cloth) 1. Peru—History—Conquest, 1522-1548. 2. Peru—History—1548-1820. 3. Incas—History. I. Julien, Catherine J. II. Title. F3442.Y8513 2006 985'.02—dc22 2006010681 eISBN: 978-1-60384-016-3 (ebook) Contents Acknowledgments vi Introduction vii Selected Bibliography xxx Maps xxxvi HISTORYOFHOWTHESPANIARDSARRIVEDINPERUAND WHATHAPPENEDTOMANCOINCADURINGTHETIMEHE LIVEDAMONGTHEM (Relasçion de cómo los españoles entraron en el Peru y el subçeso que tubo Mango Ynga en el tiempo que entre ellos biuio), Vilcabamba, 6 February 1570 1 Appendix: Memorial,1565 170 Index 173 v Acknowledgments The work for this project was supported by a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship at the John Carter Brown Library and by a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship. Travel funding for archival re- search in Spain was provided by the Burnham-Macmillan Fund of the His- tory Department at Western Michigan University. I thank the staff in the library of the Escorial for their assistance in allowing me to see the origi- nal manuscript and for making a copy of it. My greatest debt is to Ken- neth Mills for his thorough reading of the manuscript and suggestions for revision. vi Introduction In the History of How the Spaniards Arrived in Peru(1570), Titu Cusi of- fers Philip II, king of Spain, an account of all that had happened follow- ing the arrival of Francisco Pizarro and his men on the coast of the Inca empire—the largest native polity in the Americas. What motivated the cre- ation of the Historycan only be guessed. Titu Cusi may have been trying to secure the implementation of the agreement he had negotiated with the king’s representatives as the recognized head of the Inca dynasty. The work involves much more than diplomacy, however. Titu Cusi narrates the story of the alliance made between his father, Manco Inca, and Francisco Pizarro just as the latter arrived in Cusco in late 1533. In Cajamarca, Pizarro had executed Atahuallpa, who had just won a fratricidal war that left deep divisions in the Inca dynastic elite. When Pizarro met Manco Inca, a half-brother of Atahuallpa’s, the two joined forces out of mutual need to defeat Atahuallpa’s remaining armies. Titu Cusi also tells about his own dealings with the Spaniards after Manco’s death in 1544, but the centerpiece of the story is how the alliance between his father and Fran- cisco Pizarro unraveled. In it, he combined the forms of the Spanish his- torical narrative with what appears to be an Inca rhetorical genre. The result is a unique literary and historical achievement that forces us to re- consider how the story of the conquest has been told. The History is one of only a handful of historical narratives to be au- thored by native Andeans in the century after the Spanish arrival. The scarcity of such narratives probably stems, at least in part, from the ab- sence of an Andean alphabetic writing system prior to that time. Of these narratives, Titu Cusi’s stands out because it is the earliest; it is the only narrative authored by an Inca; its author was theInca (the recognized head of the dynastic line); and it was written from Vilcabamba, a province then only tenuously subject to Spanish authority. Though the full title of Titu Cusi’s narrative—History of how the Spaniards arrived in Peru and what happened to Manco Inca during the time he lived among them—is taken from the heading of the first chapter about his father, the story actually begins with the arrival of the Spaniards on the coast of the Inca empire. During the time covered in the History,the Spaniards overthrew the Inca vii viii Introduction elite and usurped authority over the largest native state in the Americas, establishing the de facto rule of Spain in the Andes. Although we still use the word “conquest” to refer to this period of initial engagement between Europeans and native Andeans, we now realize that the capture of Ata- huallpa was an initial salvo in a much longer war, and that the Incas may not have even guessed at Spanish intentions for some two years after the events at Cajamarca. Interestingly, Titu Cusi does not use the term “con- quest.” Instead, he says that the Spaniards “arrived” and events “hap- pened” during the time his father “lived among them.” He portrays his father as naïve and foolish, a man who ignored his closest advisers’ calls for resistance and inadvertently allowed the Spaniards to take the Inca em- pire away from him. His story is another telling of the traditional story of the conquest, containing truths as well as new forms of bias. In the traditional version of the “conquest” of Peru, control passed from Inca to Spanish hands with the capture of the Inca Atahuallpa in Cajamarca in November 1532. The official accounts, written by Pizarro’s secretaries, represent Atahuallpa’s capture as a battle between Spaniards and Incas. Spanish domination was decisively established when the Incas lost the fight. A long period of rooting out pockets of resistance followed, finally ending with the campaign against the Vilcabamba Incas in 1572. When relating the history of the period, modern scholars tend to use lan- guage that reflects their basic acceptance of the story told in the official accounts: control over the Andes effectively passed to Europeans upon Atahuallpa’s capture; the Incas appointed by Pizarro after Atahuallpa’s death were “puppets”; the ensuing military events were “rebellions.” But, as Titu Cusi’s Historymakes clear, there are other ways to tell the story. One account situates the events of the Spanish arrival within the broader context of Andean history (Rowe, “Como se apoderó”). A war had broken out after the death of Huayna Capac, Manco Inca’s father, about 1528. Huayna Capac had been campaigning in Ecuador at the time of his death, and his son Atahuallpa took effective control of the army. Another son, Huascar, was named Inca ruler in Cusco, the center of the empire and homeland of the Incas. War soon broke out between the two brothers. Atahuallpa’s army, led by some of his father’s most capable generals, outmaneuvered Huascar near Cusco and took him captive. At the very mo- ment Pizarro captured Atahuallpa, Huascar was a prisoner of Atahuallpa. Atahuallpa, afraid that Pizarro might prefer to ally himself with Huascar, had