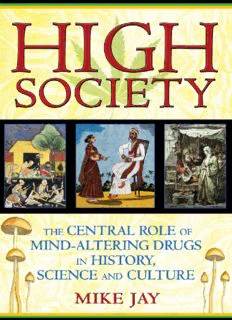

High Society The Central Role of Mind-Altering Drugs in History, Science, and Culture PDF

Preview High Society The Central Role of Mind-Altering Drugs in History, Science, and Culture

2 3 About the Author Mike Jay has written widely on the cultural history of science and medicine, and is a leading specialist in the study of drugs across history and cultures. He is the editor of Artificial Paradises, an anthology of drug literature, and author of the widely acclaimed Emperors of Dreams, a narrative history of drugs in the nineteenth century, and The Atmosphere of Heaven, on the discovery of nitrous oxide. His critical writing on drugs and their histories has appeared in The Guardian, The Daily Telegraph and The London Review of Books. 4 Other titles of interest published by Park Street Press include: The Psychotropic Mind Salvia Divinorum The Psychedelic Journey of Marlene Dobkin de Rios See our website www.parkstpress.com 5 6 CONTENTS Foreword A Universal Impulse High Societies - The Evolution of Drugs - Animal Intoxication - Drugs and Shamanism - Drugs and Culture - The Culture of Kava - The Culture of Betel - Drug Prohibitions - Drug Subcultures - The Cultures of Ecstasy From Apothecary to Laboratory What Is a Drug? - Drugs in Antiquity - Renaissance Herbals - Witches and Flying Ointments - The Invention of Laudanum - Linnaeus and the Enlightenment - The First Synthetic Drugs - Opium and the Romantics - The Club des Haschischins - Freud and Cocaine - Addiction and Drug Control - Mescaline, LSD and Beyond - Drugs of the Future The Drugs Trade Drugs of the New World - The Psychoactive Revolution - Tobacco in China, Tea in Europe - The Opium Wars - The Anti-Opium campaign - Temperance and Prohibition - The ‘War on Drugs’ - Epilogue: The Decline of Tobacco Notes and Further Reading Acknowledgments Index Copyright 7 Foreword The fundamental urge to alter our consciousness in significant but controllable ways is, it seems, part of our hard-wiring. Very few people live their lives without using some kind of mind-altering substance, be it a cup of coffee, a glass of wine, sleeping pills, cigarettes or betel. The abundance of intoxicants and the myriad ways in which they are woven into the fabric of cultures around the world have left an extremely rich visual and material record, which this book explores. Moreover, drugs have significantly influenced social and cultural movements, defining entire subcultures from coffeehouses and opium dens to modern-day raves. Mind-altering substances answer the deep desire – need, even – we have to enhance and extend our ordinary experience of life. As a habit, taking drugs seems directly related to our core interest in experimentation: the indulgence of our inclination to wonder ‘What if?’. Accordingly, scientific enquiry into this aspect of human experience has progressively deepened and broadened in modern times. Since the eighteenth century, the development of new drugs has played out against a backdrop of pharmacological investigation and application, with traditional substances derived from plants and herbs augmented and then supplanted by synthetic chemicals. Though inevitably more subjective, the actual experience of drug consumption has also become an increasing focus of enquiry, frequently through self-experiment. Here the approach of science has gone hand in hand with the practices of art to explore the impact of drugs on creativity. More recently, in a century when the social impact of drug consumption has emerged as an ever-more-threatening ‘social menace’, science has also been called upon for guidance in tackling the problem of addiction. 8 A waiter pours a drink for a customer in a painting of an eighteenth-century London coffee house (detail). (© The Trustees of the British Museum) 9 Ceremonial drinking of kava in the Friendly Islands (Tonga), engraving by W. Sharp after John Webber (detail). (Wellcome Library, London) A Mandarin sits on a mat, smoking a long opium pipe, in a coloured aquatint by Swiss artist Sigismond Himely, c. 1820. (Wellcome Library, London) High Society is an intriguingly multi-layered account of humanity’s long and elaborate dance with mind-altering drugs. It was written as an extension of Mike Jay’s advisory and curatorial work on an exhibition of the same name presented at Wellcome Collection, London. Wellcome Collection was not conceived as a conventional venue for the dissemination and popularization of scientific knowledge. Instead its approach has been to think in public – ‘out loud’, as it were – about medical science and its connections with art and the rest of life. The subject of drugs, with its rich history of scientific experimentation, literary and artistic inspiration, economic opportunity, societally encoded behaviour and fundamental biological effects, is an ideal focus for an institution dedicated to investigating science as a vibrant part of culture. Ken Arnold 10

Description: