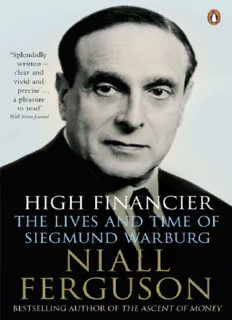

High Financier: The Lives and Time of Siegmund Warburg PDF

Preview High Financier: The Lives and Time of Siegmund Warburg

NIALL FERGUSON High Financier The Lives and Time of Siegmund Warburg ALLEN LANE an imprint of PENGUIN BOOKS Contents List of Illustrations Preface 1 Siegmund and his Cousins 1 The First World Revolution 3 The Degeneration of a Republic 4 Exile 5 Trading against the Enemy 6 Restoring the Name 7 Atlantic Unions 8 The Financial Roots of European Integration 9 The Rhythm of Perfection 10 Britain’s Financial Physician 11 The Malaise in our Western World 12 Expensive Lessons 13 The Education of an Adult Appendix: Graphology Illustrations Notes Bibliography Acknowledgements For Charles S. Maier colleague and friend The ego, this mysterious conception, hypothetical motor of human beings, is a clear unity only in the physical sense but a mixture of many different and contradictory elements … Siegmund Warburg, 1965 The main argument for such an autobiography is the great variety of activities in which I have been involved in my life – as a man born and educated in Germany, who started his career there but had later to establish his home and professional basis in England; as a man who lived in a way several lives, that of a German scholar, of an international banker, of an adherent to Judaism and above all of an ardently enthusiastic citizen of Britain, his country of adoption. Siegmund Warburg, 1976 List of Illustrations 1 The Alsterufer Warburgs (George Warburg) 2 The Mittelweg Warburg brothers (M. M. Warburg & Co. KGaA) 3 Aby M. Warburg (The Warburg Institute, London) 4 Max Warburgh (Ullsteinbild/TopFoto) 5 Siegmund as a baby with his parents, Lucie and Georges (GeorgeWarburg) 6 Schosss Uhenfels (George Warburg) 7 Siegmund as a boy (George Warburg) 8 Felix and Paul F. Warburg (Bettmann/Corbis) 9 Siegmund and Eva’s wedding (George Warburg) 10 Siegmund (George Warburg) 11 Siegmund with his son George (George Warburg) 12 The M. M. Warburg & Co. offices in the Ferdinandstrasse, Hamburg (M. M. Warburg & Co. KGaA) 13 Wall Street with the Kuhn, Loeb & Co. offices (Bettmann/Corbis) 14 Siegmund with his mother (George Warburg) 15 Viscount Portal (HIP/Topfoto) 16 Geoffrey Cunliffe (News Chronicle/Camera Press, London) 17 Nicolas Bentley cartoon from the Daily Mail (Solo Syndication) 18 Siegmund with Princess Margaret (George Warburg) 19 Siegmund at a ‘Saints and Sinners’ dinner (Press Association Images) 20 Theodora Dreifuss (Renata Popper) 21 The Chairman’s Committee of S. G. Warburg & Co. (The Jacques Lowe Estate) 22 Henry Grunfeld (Tony Andrews/Financial Times Syndication) Preface We should not deceive ourselves into thinking that when we die we shall be remembered intensively for more than a limited number of days – except by a very few people to whom we are bound by the closest ties of friendship and emotional attachment. 1 Siegmund Warburg, 1974 I For better or for worse, the City of London today is the world’s preeminent international financial centre. Along with Wall Street, it is a place synonymous with the ascent of money. Where other sectors of the British economy languished after the Second World War, finance thrived, latterly to the point of dangerous preponderance. This was not foreordained. In 1945 London was to all intents and purposes dead as a financial centre, its business ‘catastrophic’, in the words of one banker, its grand Victorian counting houses one-third destroyed.2 The era of ‘gentlemanly capitalism’ appeared about as likely to revive and endure as the British Empire the gentlemanly capitalists had so loyally served. That the City rose, literally as well as phoenix-like, from the ashes left by the Blitz was a historical surprise harder to explain than would have been its irrevocable demise, had that in fact occurred. This is a biography of the man who, more than any other, saved the City. From the moment he hit the headlines with the first ever hostile takeover bid in 1959 until his death in 1982, Siegmund Warburg was the City’s presiding genius, a brilliant exponent of high finance – haute banque, as he liked to call it – who saw with unrivalled prescience the possibilities of global financial reintegration after the calamities of the Depression and two world wars. He was the architect of that transformation of economic institutions which led the Western world back to the free market after the mid-century excesses of state control. Beating down the barriers that had been erected to limit the international flow of capital, Warburg made possible the resurrection of London as the world’s principal centre for cross-border banking. His career illuminates nearly all of the most important historical questions about the role of finance in shaping modern Britain: Why was it that bankers of Jewish origin played such a leading role in British financial history? Did the gentlemanly capitalism of the City of London undermine the performance of the economy of the United Kingdom and accelerate Britain’s decline as a manufacturing power? Did the City, in alliance with the ‘gnomes of Zurich’, thwart the ambitions of the Labour Party to modernize Britain’s economy in the 1960s? Why did financial deregulation end up benefiting foreign banks more than British banks in the period after Warburg’s death? Yet these questions are not the best arguments for this biography. For Warburg was also, as he himself put it, ‘a man who lived in a way several lives, that of a German scholar, of an international banker, of an adherent to Judaism and above all of an ardently enthusiastic citizen of Britain, his country of adoption’.3 He was a scion of one of the great German-Jewish banking dynasties. He was also a politician manqué. Few figures in modern financial history have simultaneously played such an influential political role, albeit largely behind the scenes. As a young man, Warburg had intended to go into politics. The rise of Hitler shattered his ambitions. Yet even as an exile in 1930s England he retained his passion for politics. He was among the most outspoken City opponents of the policy of appeasement. And, after the war, he emerged as a highly influential proponent of European integration. Indeed, the part Warburg played in what has hitherto been the secret history of European unification – the process whereby Europe was financially as well as politically integrated – is among the most historically significant revelations of this book. Bankers, it now becomes clear, were as important as bureaucrats in propelling forward the project for a united Europe, and no banker did more to advance this cause than Siegmund Warburg. He consistently sought to accelerate the process whereby European institutions, in both the public and the private sector, were linked together across national borders. And he strove for decades to overcome the resistance of the British Establishment – the political and civil service elites of Westminster and Whitehall – to the idea that Britain should be a fully fledged member of a European Union. At the same time, Warburg remained a committed Atlanticist, seeing no contradiction between Europe’s economic integration and its strategic contradiction between Europe’s economic integration and its strategic dependence on the United States. Despite the fact that he had opted for the City over Wall Street, he never lost sight of his lifelong goal of transatlantic financial integration and spent as much of his working career in New York as in Frankfurt, Hamburg, Paris and Zurich combined. His attempts to salvage Kuhn, Loeb & Co., once one of the titans of Wall Street, is one of the hitherto unwritten chapters of American financial history. Bankers, it is often said, are the real powers behind the scenes of politics. But how in practice could a banker like Warburg exert power in the post-war world? Part of the answer lies in his pioneering role in corporate finance, which put him at the very heart of successive governments’ efforts to resuscitate the ailing British economy. It was the emergence of S. G. Warburg & Co. as the masterminds of the takeover bid – beginning with the contested bid for British Aluminium – that transformed Warburg from an outsider, cold-shouldered by the snobbish old boys’ network of the City, into one of the key insiders of 1960s politics. To an extent not previously realized by historians, Warburg became one of Harold Wilson’s most trusted confidants on economic questions during the latter’s first term as prime minister. In their regular meetings, about which other Cabinet members knew little, Warburg steered Wilson in the direction of EEC membership and strove, vainly as it proved, to avert first the devaluation of sterling in 1967 and then the descent of Britain’s economy into the financial maelstrom of the mid-1970s. Though eternally grateful to England for the opportunities it gave him, Warburg retained a lifelong suspicion of the English social elite, attributing many of the country’s post-war problems to the deadening influence of the socially exclusive public schools and the mandarins of the senior civil service. A compulsive traveller, Warburg came to regard his own identity as multinational. Though he had been relatively swift in discerning the evil of Nazism, he never lost his attachment to German culture, and especially to the literature of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In the years after 1945, few if any refugees from the Third Reich worked harder to bring about the economic and political rehabilitation of West Germany – to the extent of working closely with men who had played less than edifying roles under Hitler. At the same time, he became keenly interested in the fate of the state of Israel, first as a defender of the Zionist cause in the late 1960s, and later as a bitter critic of the Israeli

Description: