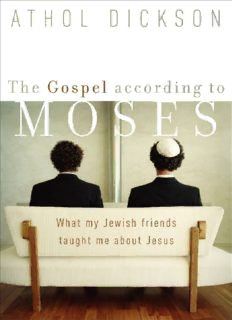

Gospel according to Moses, the : what my jewish friends taught me about Jesus PDF

Preview Gospel according to Moses, the : what my jewish friends taught me about Jesus

© 2003 by Athol Dickson Published by Brazos Press a division of Baker Publishing Group P.O. Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516-6287 www.brazospress.com Ebook edition created 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. ISBN 978-1-5855-8244-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Unless otherwise marked, Scripture is taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version®. NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide. www.zondervan.com Scripture marked JPS is taken from Tanakh, The Holy Scriptures, The New JPS Translation according to the Traditional Hebrew Text, (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1985). Scripture marked KJV is taken from the King James Version of the Bible. Scripture marked NRSV is taken from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. Published in association with the literary agency of Alive Communications, Inc., 7680 Goddard Street, Suite 200, Colorado Springs, Colorado 80920. For my mother, Mary Katherine Garrett Dickson. She considered it all joy. Contents Cover Title Copyright Page Dedication Page Introduction 1.God on the Spot Dealing with Doubts 2.Our Mutual God Finding Meaning in Monotheism 3.God in Chains Why God Lets Me Suffer 4.Yes and Yes Understanding Scriptural Paradox 5.The Beautiful Terror Approaching the God of “Fire and Brimstone” 6.Spiritual Suicide Why It Is So Easy to Be Bad 7.Pitching Tabernacles Finding Connections between Obedience and God’s Grace 8.The Small Print Christians and the Law of Moses 9.Up from the Well Reconciliation with God 10.Skeletons in My Closet Evil Christians in Spite of Jesus 11.One and All The Trinity and Monotheism 12.The Word in the Word Jesus in the Hebrew Scriptures 13.One Way Are Jews Going to Hell? Notes Introduction A Stranger among You The Torah was given in the desert, given with all publicity in a place to which no one had any claim, lest, if it were given in the land of Israel, the Jews might deny to the Gentiles any part in it. —Mekilta on Exodus 19:2[1] Life’s most important moments are often disguised as the commonplace. Take this moment for example. As Philip and I make small talk about business and family, we say the things one says when catching up with a casual aquaintance. Then the conversation shifts to religion. He says his Reform Jewish temple has interfaith gatherings every year to reach out to members of other religions. Since I am a Christian, he wants me to come to a thing called “Chever Torah,” in honor of something else he calls an “interfaith Shabbat.” My ignorance of Judaism is prodigious, so I ask Philip the meaning of Shabbat (it means “Sabbath”) and of course those mysterious words, Chever Torah (the “Torah Society,” or “Torah Group”). Chever Torah, says Philip, is basically a Bible study. Will I come? Unaware that Philip’s simple invitation will change my life as a Christian forever, I accept. Two weeks later, filled with trepidation at the thought of studying the Scriptures with people who don’t believe in Jesus, I knot my tie and head to temple. There I enter a hall filled with about one hundred and fifty people, half of whom are members of a local church invited for the occasion. Chever Torah meets in a lofty room clad in brick. To my surprise, the place reeks of modernity. I am disappointed, having hoped to experience something more along the lines of dark wood paneling and rough-cut ashlars, preferably lit by candles and partially obscured by wavering tendrils of incense. But the crowd sits at rows of ordinary folding tables draped with white paper. There are no dated black hats, no unkempt beards, no parchment scrolls. These people are as hopelessly modern as the architecture. Many have large books open on the tables before them. Bibles, I suppose. Peering surreptitiously at a woman’s copy across the way, I observe the controlled chaos of Hebrew text on the pages, row after row of dots and squiggles. My disappointment fades slightly. At least this is something Jewish. A man in a dark suit rises to speak. For the benefit of the Christians present, he introduces himself as Rabbi Sheldon Zimmerman. Although he wears no yarmulke or prayer shawl, his full gray beard and proper bald spot lend the bookish air one expects of a rabbi. He speaks of his pleasure at seeing so many new faces this morning, his large brown eyes sparkling as he surveys the crowd. Rabbi Zimmerman is good with words, and I begin to hope something unusual might yet be salvaged from the otherwise mundane morning. Then the rabbi identifies a man sitting to his left as Dr. George Mason, pastor of Wilshire Baptist Church. His complimentary remarks about Dr. Mason sound ominously like the introduction of a featured speaker. This suspicion is bitterly confirmed when the rabbi steps back and the pastor approaches the podium. My mood turns sour. Have I been lured away from my comfortable Saturday morning routine with false expectations of the exotic, only to be subjected to a Bible study led by a fellow Christian? I sigh and settle in, feeling the inevitable sermon-inspired drowsiness rise behind my eyelids. After five minutes, it is clear that Dr. Mason is every bit as fine a public speaker as the rabbi, but this does little to improve my frame of mind. Then a hand is raised, an elderly gentleman near the front asks the pastor a question, and my grouchy train of thought is stopped dead in its tracks. This is not a Christian kind of question. It is more aggressive somehow, less deferential to the subject at hand. It may not be asked in the exotic, incense-tinted atmosphere I had hoped for, but it is different nonetheless . . . definitely different. I sit a bit straighter. Perhaps I will get some sense of the Jewish world after all. As it happens, I get much more than that. The instant Dr. Mason finishes answering the old man’s question, hands shoot up everywhere. Penetrating comments fly across the room with astonishing candor as these Jews become determined miners sifting a rich stream of biblical material with questions unbounded by fear of heresy and unlimited by preconceived notions. I crane my neck to see what kind of people would ask such remarkable things, but these Chever Torah Jews still look like my father, or my wife, or my friend—the usual faces one sees in a crowd. Who could have known? All too soon it is over. Outside on the sidewalk, Philip asks for my reaction. Basking in the afterglow of this Chever Torah experience, I gush, “I loved it! I wish I could come every week!” After a moment’s pause, Philip says, “Well, I don’t see why you couldn’t.” And so began the five-year odyssey that led me to write this book. I am ill prepared to teach a Jew about his or her own religion, and fortunately not foolish enough to try. Where important differences between Judaism and Christianity arise within these pages, I will do my best to explain both perspectives fairly, but Reform Jews will undoubtedly have some objections to my presentation of their perspective. For this I apologize in advance. Jewish friends have read rough drafts of this work and attempted to correct my errors, but any remaining mistakes are mine alone and not the responsibility of those who tried to help. Among those who read early drafts of this book is Philip, the casual aquaintance who first invited me to Chever Torah. Philip has become my dearest friend over the years and is a very devout Jew. He expressed concern that Jews who do not know me may mistake my purpose, believing this is just one more thinly veiled attempt to convert them to Christianity. It is not. But after five years at Chever Torah, I know why Philip is worried, so let me be clear about my intentions. In The Gospel according to Moses, I will show that Christianity is a reasonable response to the books of Moses, the writings, and the prophets. For Christian readers, I hope this will be a welcome confirmation that the most basic tenets of our faith are rooted in the earliest moments of creation, in the Garden, in the cool of the day. Ours is a Torah-based faith. For Jewish readers, I hope this will demonstrate that our religious differences flow from a genuine divergence of informed opinion on the meaning of the Hebrew Scriptures, not from scriptural ignorance. Some of my friend Philip’s concern about Jewish suspicion of my motives may also be relieved if I promise not to disguise my beliefs only to unveil them when the reader’s back is turned. Within these pages I will describe how my faith has been informed and enriched by contact with Jews and Judaism, but make no mistake: this book is about Christian faith. And just as honesty forbids the disguise of my bias within these pages, it also means I must not compromise basic tenets of the Christian faith, not even to build bridges. I agree wholeheartedly with these words by a famous atheist: The other day at the Sorbonne, speaking to a Marxist lecturer, a Catholic priest said in public that he too was anticlerical. Well, I don’t like priests who are anticlerical any more than philosophers who are ashamed of themselves. —Albert Camus[2] Like Camus, I am not much for the easy religious pluralism one often hears espoused today. The differences between Christianity and Judaism are too important to ignore or minimize. That does not mean there is little value in learning from each other. When I first wrote this book, the newspaper headlines were already filled with churches burning, synagogues defaced, and hate-filled men attacking Christian and Jew alike. While this book was being considered for publication, Muslim terrorists inflicted history’s most deadly attack on the United States in the name of their religion. In this time of increasing violence against persons of faith by those who hate us for our specific beliefs, or simply because we do believe, all “people of the book” should stand together. But we are often divided by misunderstandings, which have grown through centuries of isolation between the Christian and Jewish communities. If ever there was a time to learn the truth about our differences from each other rather than reinforce false assumptions among ourselves, it is now. And we must respect those differences, even as we search for genuine common ground and cultivate it side by side. As the novelist Tom Clancy once wrote: “One hallmark of intellectual honesty is the solicitation of opposing points of view.” So while I do intend to avoid proselytization, I have no intention of leaving the reader untouched. This applies to Christians and Jews alike. Unless we are gagged and blindfolded by preconceived ideas, all worthwhile encounters change us in some important way. Heaven knows the Jews of Chever Torah have changed me. Being a conservative Christian at a liberal Jewish temple has never been easy or painless, but I have accepted the cost because my religion teaches that constructive growth is worth a little pain.[3] Key positions of Christianity have been strongly disputed almost every week at Chever Torah by highly intelligent people who know the Scriptures well and find very different truths there. At first I responded to the challenges with dogmatic inflexibility, experiencing a range of unpleasant emotions from anger to anxiety. Only God’s subtle prodding can explain why I kept returning. Then somehow—again, I believe this can only be explained as an act of God—I found the ability to set aside my preconceived notions and truly hear the new ideas these Jews tossed back and forth. From that moment on, the people of Chever Torah began to coach me in that decidedly Jewish pastime: wrestling with God. Now, after years of Bible study among them, I have learned to think about important things like faith and obedience, justice and mercy, and rebellion and redemption in Jewish ways, and in so doing have found deeper meanings within every word uttered by Jesus and his apostles. Strange as it may seem, the Jewish perspective of Chever Torah has given me a richer, more solid foundation for my own faith. It has become a cliché in Christian circles to say, “Judaism is the root of Christianity,” but Chever Torah has breathed real life into those words for me. I have uncovered my Jewish roots, examined them, and fed upon the nourishment that flows up into the sheltering branches of my own belief. Years ago I exposed myself to the possibility that Judaism might have great truths to offer, and Chever Torah rewarded my open mind with radical improvements in the way I live and view my Christian faith. In the same way, with openness and proper respect for the importance of ideas, it is my earnest hope that something within the covers of this book will challenge the preconceived notions of every reader and result in a deeper relationship with the One who made us all. one God on the Spot Frequently questions or objections, which men might raise to something in God’s conduct of affairs in the world, are put into the mouth of the angels, to give God, so to speak, occasion to explain or justify his ways. —Bereshit Rabbah, 8, 3 “What was the difficulty for Rashi?” Rabbi Peter Berg, the newest addition to the staff at temple has just posed a question that is centuries old. The tall and slender rabbi searches our faces for an answer. It is a question rabbis love to ask, a question I too will learn to cherish. The medieval French rabbi and Bible scholar known as Rashi (an acronym for his full name, Rabbi Shlomo ben Isaac) found many difficulties in the Bible. These included apparent contradictions, apparent flaws in logic, enigmatic stories that occupy pride of place within the text yet have no apparent rhyme or reason, verses that seem out of context, and words, phrases, or entire stories that are repeated for no clear purpose. In Rabbinic Judaism, such difficulties are called koshim. They can be volatile, dangerous stuff. Once they drove me far from God. My foundation in Bible study was laid in my parents’ devout Christian home, where I began memorizing simple Bible verses almost before I could read. I remember “Bible drills” when I was seven or eight years old. My Sunday school class was given a verse to look up as quickly as possible. The first to find it won something, usually a little sticker to affix inside the cover of his or her Bible. By the time I was eight or nine I had already been taught much of the doctrine that the church has long associated with each of these verses: the nature of sin, faith, and redemption, and the attributes of God and humanity. But by the age of sixteen, I had more questions than answers. For example, there are two accounts of the gathering of the animals into Noah’s ark, the famous one when they come in pairs, and another, rarely mentioned in churches, in which they come in sevens. Why two accounts? Why pairs in one and groups of seven in the other? Such difficulties in a document I had been taught to view as the

Description: