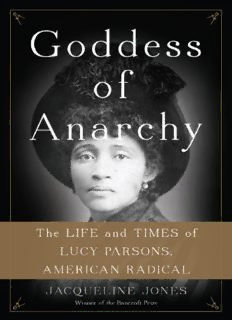

Goddess of Anarchy: The Life and Times of Lucy Parsons, American Radical PDF

Preview Goddess of Anarchy: The Life and Times of Lucy Parsons, American Radical

Copyright Copyright © 2017 by Jacqueline Jones Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. Basic Books Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104 www.basicbooks.com First Edition: December 2017 Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Jones, Jacqueline, 1948– author. Title: Goddess of anarchy : the life and times of Lucy Parsons, American radical Title: Goddess of anarchy : the life and times of Lucy Parsons, American radical / Jacqueline Jones. Description: First Edition. | New York : Basic Books, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017021023| ISBN 9780465078998 (hardback) | ISBN 9781541697263 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Parsons, Lucy E. (Lucy Eldine), 1853–1942. | Anarchists—United States—Biography. | Working class—United States—History. | Labor movement—United States—History. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Women. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY Historical. | HISTORY United States 20th Century. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY Political. | HISTORY Modern 20th Century. Classification: LCC HX843.7.P37 J66 2017 | DDC 355/.83092 [B]—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017021023 ISBNs: 978-0-46507899-8 (hardcover), 978-1-54169726-3 (ebook) LSC-C E3-20171103-JV-PC Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Introduction PART 1: AN ENDURING CIVIL WAR Chapter 1 Wide-Open Waco Chapter 2 Republican Heyday PART 2: GILDED AGE DYNAMITE Chapter 3 A Local War Chapter 4 Farewell to the Ballot Box Chapter 5 A False Alarm? Chapter 6 Haymarket Chapter 7 Bitter Fruit of Braggadocio Chapter 8 “The Dusky Goddess of Anarchy Speaks Her Mind” Chapter 9 The Blood of My Husband PART 3: BLATHERKITE-GODDESS OF FREE SPEECH Chapter 10 The Widow Parsons Sets Her Course Chapter 11 Variety in Life, and Its Critics Chapter 12 Tending the Sacred Flame of Haymarket Chapter 13 Wars at Home and Abroad PART 4: THE FALLING CURTAIN OF MYSTERY Chapter 14 Facts and Fine-Spun Theories Epilogue Illustrations Acknowledgments About the Author Also by Jacqueline Jones More Praise for GODDESS OF ANARCHY Abbreviations in Notes Notes Index To Steve and Henry Introduction T HE RADICAL LABOR AGITATOR LUCY PARSONS LIVED MUCH OF her long life in the public eye, but she has nevertheless remained shrouded in mystery. Skilled in the art of rhetorical provocation in the service of justice for the laboring classes, she also offered up a fiction about her origins and denied key elements of her own past. She was born to an enslaved woman in Virginia in 1851, and twenty- one years later married a white man, Albert R. Parsons, in Waco, Texas. Together the couple forged a tempestuous dual career, first as socialists and then as anarchists, urging workers to use all means at their disposal, including physical force, to combat the depredations of industrial capitalism. Their raw rhetoric of class struggle led to Albert’s conviction on charges of murder and conspiracy related to the 1886 bombing in Chicago’s Haymarket Square, and he died on the gallows in November 1887. Among workers then and successive generations of historians since, Lucy Parsons has achieved secular sainthood by virtue of her widowhood. Yet her career transcended the fate of her famous husband. By the time Albert was executed, Lucy had gained a national reputation as an orator of considerable strength and power and as a fighter for free speech and free assembly. This reputation would remain intact from 1886 until her death in 1942. More than anyone else in her time (or since), she tended the flame of Haymarket, reminding the public of the miscarriage of justice that resulted from an unfair trial. Her story provides a window into the history of industrial and urban workers through a series of transformative eras that took place from the 1880s through the 1930s. Nevertheless, information about her personal life is as meager as her public persona was fulsome. To adoring audiences no less than curious reporters, she refused to reveal more than the most basic facts about her family, including her husband, Albert, and her two children, Albert Jr. and Lulu. During a six-month speaking tour from the fall of 1886 through the spring of 1887, she traveled to seventeen states and addressed (by her reckoning) forty- three audiences ranging in size from a couple of hundred to several thousand. At her first stop, in Cincinnati, a reporter asked about her background. The thirty- five-year-old Parsons demurred: “I am not a candidate for office, and the public have no right to my past. I amount to nothing to the world and people care nothing for me. I am simply battling for a principle.” However, Parsons was mistaken in her claim that the public had no interest in her apart from her message of a looming revolution that would overthrow capitalism.1 Public speaker, editor, free-speech activist, essayist, fiction writer, publisher, and political commentator, Parsons was one of only a handful of women of her day, and virtually the only person of African descent, apart from Frederick Douglass, to speak regularly to large audiences. She addressed enthusiastic crowds up and down the East Coast, across the Midwest, and into the Far West for well over five decades. She was a courageous advocate of First Amendment rights, notable for her confrontational tactics and what many considered her shocking language in pursuit of those rights. She had a never-wavering commitment to a free press, and the alternative periodicals that she edited or that published her writings served as a bracing corrective to the contemporary mainstream news outlets that furthered the interests of the powerful. Her stamina over the decades (she was born in a year when the average life expectancy was forty years) speaks to her deep drive: she loved the spotlight, whether that meant center-stage in a hall or a front-page, above-the-fold headline. Lucy Parsons lived through the Civil War and Reconstruction and engaged directly with the monumental issues shaping the Gilded Age, the Progressive Era, the Red Scare during and after World War I (a political movement with its origins in efforts to silence her during the late 1880s), the reactionary 1920s, and the Great Depression and New Deal. She demonstrated a remarkable prescience about the vicissitudes of modern capitalism, including the effects of technology on the workplace and the structure of the labor force; the role of labor unions as a countervailing force to corporations; the corrupting influence of money on politics; the inadequacy of the two-party system to address fundamental economic and social inequalities in American life; the cyclical depressions and recessions that hit hardworking people; the lengths to which local police forces and private security companies would go to suppress strikers and violently intimidate their leaders; and the everyday struggles of ordinary people, men and women, to make a decent life for themselves and their families. On countless occasions she defied the attempts of the authorities to silence her, and she remained uncompromising in her denunciations of an economic system that ravaged the unemployed and the white industrial laboring classes. From the early 1880s onward, Parsons held fast to the ideal of a nonhierarchical society emerging from trade unions, a society without wages and without coercive government of any kind. Neither she nor her anarchist comrades, though, appreciated the larger political significance of many Americans’ fierce ethnic and religious loyalties. And she ignored the unique vulnerability of African Americans, whose history was not merely a variation on the exploitation of the working class, but a product of the myth of race in all its hideous iterations. She and Albert lost faith in the power of words to persuade and educate, turning instead to using words to threaten and intimidate, a fatal decision that sent him and his comrades to their deaths. On her own, she favored lurid predictions about the fate that the robber barons, judges, and police would meet should she have her way, a mode of speaking that tarred all anarchists with the brush of violent revolt and alienated reformers working for incremental legislative and regulatory measures. In the Gilded Age, the collective labor actions that she and her allies championed could bring whole cities, or the national rail system, to a grinding halt, but the power of those actions obscured the fact that most American workers rejected radicalism in favor of the chimera of a humane capitalism.2 A saint, secular or otherwise, Lucy Parsons was not. Her life was full of ironies and contradictions: She was born to an enslaved woman but maintained a pronounced indifference to the plight of African American laborers, not only those in the South but also in her adopted home of Chicago. She was a frankly sexual being who presented herself publicly as a traditional wife and mother. She extolled the bonds of family, but left behind in Waco a mother and siblings whom she ignored for the rest of her life. She used her children as political props, and rid herself of her son when he threatened to embarrass her in public. She was a labor agitator who had neither the patience for nor an interest in organizing workers, an anarchist who took a long historical view but remained stubbornly oblivious to major political and economic developments that transformed post–Civil War America. She expressed a deep commitment to informed debate and disquisition, on the one hand, and, on the other, an unthinking invocation of the virtues of explosive devices. A vehement critic of government in all its forms, Parsons used the courts and police to settle personal disputes with creditors, neighbors, lovers, and even

Description: