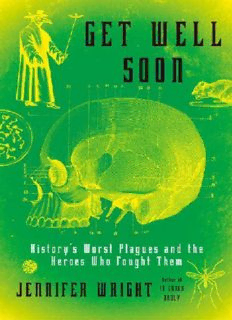

Get Well Soon: History’s Worst Plagues and the Heroes Who Fought Them PDF

Preview Get Well Soon: History’s Worst Plagues and the Heroes Who Fought Them

Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Henry Holt and Company ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For Mom and Dad. Would it kill you to go to the doctor now and then? What’s natural is the microbe. All the rest—health, integrity, purity (if you like)—is a product of the human will, of a vigilance that must never falter. —ALBERT CAMUS, The Plague I’ve got chills. They’re multiplying. And I’m losing control. —JOHN FARRAR, “You’re the One That I Want,” Grease Introduction When I tell people that I am writing a book on plagues, well-meaning acquaintances suggest I add a modern twist. Specifically: “You know, like how we’re all on our cell phones all the time.” Or selfies. A chapter on selfies. Then I reply, “No, my interest lies more with the kind of plague where you break out in sores all over your body and countless people you know and love die, rapidly, within a few months of each other, in the prime of their lives. And there is nothing you can do, and everyone is dead, and everything is death, and all of earth seems to be a vast wasteland of corpses, and, wait, here, allow me to show you some absolutely horrific pictures.” And then they say, “Excuse me, I’m just going to get another drink.” I am so happy you picked up this book because often, when I’m out chatting with people, no one really likes to hear about diseases of the past. I suspect that disinclination is largely due to plagues seeming both very grim and very remote. It’s generally better just to say that I like selfies. I think they’re fun. I like seeing pictures of my friends’ smiling faces. I like how alive they all are. It does appear that we are living in a world where the word plague has shockingly little meaning for many. To the extent that they think about plagues at all, many associate them with muddy huts, textbooks they had to read in sixth grade, and, if they are film buffs, a death figure who has a truly bewildering interest in chess. People in core countries seem to expect to die at age ninety in a nursing home. They do so with good reason: if conditions continue uninterrupted, 50 percent of the children born in the year 2000 will live to be a hundred years old. If conditions continue uninterrupted. We have been living in an age of improbable luck. We have experienced nearly thirty years without a disease—that we do not know how to combat— killing upward of thousands of otherwise healthy young people in those core countries. I can’t say whether this good fortune will run out—I hope it won’t— but it always has in the past. We just like to forget this disagreeable fact. Forgetting is soothing and probably in our nature. But disregarding, and being ignorant of, plagues of the past makes us more, rather than less, vulnerable to inevitable ones in the future. Because when plagues erupt, some people behave amazingly well. They minimize the level of death and destruction around them. They are kind. They are courageous. They showcase the best of our nature. Other people behave like superstitious lunatics and add to the death toll. I wish I had the scientific knowledge to talk about how to make vaccines or cures that might eradicate illness, but I don’t. This book isn’t just for future Nobel Prize winners, as much as I am impressed by and rooting for them. Because whether plagues are managed quickly doesn’t just depend on hardworking doctors and scientists. It depends on people who like to sleep in on weekends and watch movies and eat French fries and do the fantastic common things in life, which is to say, it depends on all of us. Whether a civilization fares well during a crisis has a great deal to do with how the ordinary, nonscientist citizen responds. A lot of the measures taken against the plagues discussed in this book will seem stunningly obvious. You should not, for instance, decide diseased people are sinners and burn them at a literal or metaphorical stake, because it is both morally monstrous and entirely ineffective. Everyone would probably theoretically agree with this statement. But then a new plague crops up, and we make precisely the same mistakes we should have learned from three hundred years ago. I recently read in a history book that you ought not view the past through a modern-day lens. It supposed that instead you should consider different eras as

Description: