Frightmares: A History of British Horror Cinema PDF

Preview Frightmares: A History of British Horror Cinema

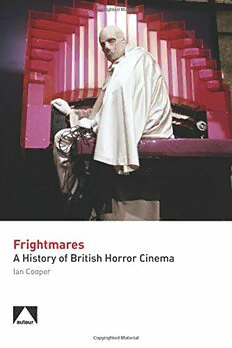

Frightmares F r A History of British Horror Cinema ig h t m Ian Cooper a r e s The horror film reveals as much, if not more, about the British psyche as the more respectable A heritage film or the critically revered social realist drama. Yet, like a mad relative locked in the H i s attic, British horror cinema has for too long been ignored and maligned. Even when it has been t o celebrated, neglect is not far behind and what studies there have been concentrate largely on the r y output of Hammer, the best-known producers of British horror. But this is only part of the story. It’s o f a tradition that encompasses the last days of British music hall theatre, celebrated auteurs such as B r Alfred Hitchcock and Roman Polanski and opportunistic, unashamed hacks. i t i s Frightmares is an in-depth analysis of the home-grown horror film, each chapter anchored by close h H studies of key titles, consisting of textual analysis, production history, marketing and reception. o Although broadly chronological, attention is also paid to the thematic links, emphasising both the rr o wide range of the genre and highlighting some of its less-explored avenues. Chapters focus on the r C origins of British horror and its foreign influences, Hammer (of course), the influence of American i n International Pictures and other American and European filmmakers in 1960s Britain, the ‘savage e m Seventies’ and the new wave of twenty-first century British horror. The result is an authoritative, a ccIitGHAwnhaoiunaw ienAtmtrec wec bumhCpui.aatecrraeu oosefP.utto hcoe urrbkeub’p s’ornstl .iech sDsoFhoreivkrei. nueesWivsgkn i o alza’asnny l s,ldA flcfid, odrlummewveeoo enIfcs orwhta r Pat reviprimtseeue spsbrese ol vai‘rcCreniaetrudat silr n,ot aewotnualyg atd, rbhse”ay o.npp HrAthu, ebibueeral ttsihessa’ heauisnsdeeri d rnwiinin geir n s2isGt u0t(2ee2r10rnv071me 1.a1y2a sn)aot nyufa. dndtHh dydii sseoi ssfimf c crBrousirtbsri ntrbe egedon xM otbulkyyeb, coeHtohrnoaem rnW rHpto lirefite TcaIetSahidBlnldfiNk gon 9o afd7a s8fAe - s0“Brlf-t o9rrGue9ind3tedi0esyno7 h 1e oo7 r-fa3f -l7 Ia FAIan rH Cigiosohtpoetrrmy oafr Bersitish Horror Cinema n Auteur Publishing Co o p AuteurPub er Front cover photograph: The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971) © American International Pictures, courtesy Stephen Jones (www.monstersfromhell.co.uk) 9 780993 071737 Frightmares Cover v1.indd 1 26/02/2016 22:34 Frightmares Frightmares v3.indd 1 28/02/2016 16:41 Frightmares v3.indd 2 28/02/2016 16:41 Frightmares A History of British Horror Cinema by Ian Cooper Frightmares v3.indd 1 28/02/2016 16:41 Acknowledgements I’d like to thank John Atkinson at Auteur for saying yes to this project (appropriately enough on a Halloween). His suggestions, advice and patience are very much appreciated. Without him, this book wouldn’t have happened. I also want to thank Garry Johnson and Gav Whitaker, aka Gav Crimson, who provided me with some useful material. I’m grateful to everybody who helped me out with ideas and thoughts, either in (ahem) real life or through social media. I do owe a particular debt to the following: Brecht Andersch, Dan Berlinka, Scott Bradley, Robert Chandler, Hugh Kenneth David, Jackie Downs, J. Marie Gregoire, Jeanie Laub, Neil Mitchell, Joseph Marr and the late Dan Tunstall. First published in 2016 by Auteur 24 Hartwell Crescent, Leighton Buzzard LU7 1NP www.auteur.co.uk Copyright © Auteur Publishing 2015 Designed and set by Nikki Hamlett at Cassels Design Printed and bound in the UK Cover: The Abominable Dr Phibes (1971) © American International Pictures, courtesy Stephen Jones (www.monstersfromhell.co.uk) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the permission of the copyright owner. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: paperback 978-0-9930717-3-7 ISBN: ebook 978-0-9930717-4-4 Frightmares v3.indd 2 28/02/2016 16:41 Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: ‘It’s Alive!’ The Birth of Home-Grown Horror ....................................................................23 Chapter 2: Hammer – Studio as Auteur ........................................................................................................51 Chapter 3: The American Invasion – Camp and Cruelty. ......................................................................97 Chapter 4: Soft Sex, Hard Gore and the ‘Savage Seventies’ .............................................................115 Chapter 5: ‘Bloody Foreigners’ – New Perspectives .............................................................................151 Chapter 6: Rising from the Grave ...................................................................................................................169 Conclusion ....................................................................................................................................................................195 Footnotes ......................................................................................................................................................................197 Bibliography ..................................................................................................................................................................199 Index ................................................................................................................................................................................205 Frightmares v3.indd 3 28/02/2016 16:41 Stills information All reasonable efforts have been made to identify the copyright holders of the films illustrated in the text and the publisher believes the following copyright information to be correct at the time of going to press. We will be delighted to correct any errors brought to our attention in future printings and editions. The Ghoul © Gaumont British; Dead of Night © Ealing Studios/Canal+; The Mummy, The Vampire Lovers, Vampire Circus, Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell, Dracula AD 1972, The Satanic Rites of Dracula © Hammer Films; Horrors of the Black Museum © Anglo- Amalgamated; Night of the Demon, 10 Rillington Place © Columbia Pictures; The Masque of the Red Death, The Abominable Dr Phibes © AIP; Theatre of Blood © Harbour Productions; Horror Hospital © Noteworthy Films; The Offence © Tantallon/UA; Frenzy © Universal Pictures; Frightmare © Peter Walker (Heritage) Ltd.; Repulsion © Compton Films; Vampyres © Lurco Films; Dog Soldiers © Kismet Entertainment; Kill List © Warp X/Rook Films. Thanks to Stephen Jones (monstersfromhell.co.uk) for his assistance in researching and supplying a number of these stills. Frightmares v3.indd 4 28/02/2016 16:41 Introduction London is a city which has never been slow to exploit its violent and lurid history. There are no longer severed heads mounted on London Bridge or public executions at Tyburn but the capital city retains its dark glamour. One can visit the Chamber of Horrors at Madame Tussaud’s wax museum off Baker Street and encounter infamous killers such as Dr. Crippen (played on screen by Donald Pleasence) and John Christie (Richard Attenborough). There are also facsimilies of letters purportedly from Jack the Ripper on display, written (of course) in red ink. In the London Dungeon, as well as interactive exhibits illustrating torture and bubonic plague, the Jack the Ripper experience offers an animated restaging of one of Saucy Jack’s crimes. Until the attraction was extensively overhauled, there were graphic autopsy photos of mutilated women on display. Want more Jack? You can also take a Ripper Tour along the back alleys of Whitechapel, passing close to The Blind Beggar pub on Whitechapel Road where the gangster Ronnie Kray shot George Cornell through the eye. (Rumour has it the bullet passed through the unfortunate Cornell’s head and hit the jukebox, which started playing ‘The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore’ by The Walker Brothers.) Whitechapel Road is also the location of the London Hospital where John Merrick, The Elephant Man who inspired the gothic David Lynch film, lived for the last four years of his life and it was also where an enterprising waxwork show depicting the Ripper murders was set up in 1888, unable even to wait until the murder cycle had finished before capitalising on it. In Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula (1897), one of the Count’s London addresses is in Whitechapel. The Ripper walking tours – they’ve proved so popular there are a number of competing firms providing them – traditionally end in The Ten Bells pub, which contains various items of Ripperabilia, including a handsome, wall-mounted Victim Board. Indeed, from 1976 until 1988 the pub was actually called The Jack the Ripper, until protests by feminist groups led to it reverting to The Ten Bells. Across town in Kensington, one can go to see Hitchcock’s old house, marked with a blue plaque. From there it’s just a short walk to The Goat tavern, where John George Haigh, the acid bath killer, met a wealthy fairground owner who he would go on to batter to death before drinking a cup of his blood. Until a few years ago, Haigh was name-checked on a plaque inside the pub. Upon his arrest, he was keen to exploit his new-found notoriety and became an enthusiastic participant in the ghoulish fascination his crimes aroused.He played the role of the urbane English murderer, always appearing impeccably dressed and referring to his arrest as ‘this little pickle’. It’s surely a measure of how skillfully Haigh played the archetypal English cad that when he was immortalised on film it wasn’t by the sinister likes of Pleasence or Attenborough but by the comic actor Martin Clunes (in the TV movie A is for Acid [2002]). Haigh’s legal defence was paid for by the News of the World, in return for the exclusive rights to his story. Sentenced to death for six murders, he bequeathed his best suit to Madame Tussaud’s. His likeness can still be seen there, alongside that of Dennis Nilsen, who killed 15 young men between 1978 and 1 Frightmares v3.indd 1 28/02/2016 16:41 FRIGHTMARES 1983.1 Nilsen picked up one of his victims in Piccadilly Circus, a one-time hangout for rent boys and close to another of Count Dracula’s houses. It’s in Piccadilly where the Count achieves his desire: ...to go through the crowded streets of your mighty London, to be in the midst of the whirl and rush of humanity, to share its life, its change, its death and all that makes it what it is. (Stoker 1897: 31) Nilsen picked up most of his victims in the Golden Lion pub on Dean Street in Soho, 5 minutes walk from Piccadilly Circus. Soho, of course, has long been associated with the film industry and its seedy sibling, the porn business. The Golden Lion was the local of US grindhouse auteur Andy Milligan during his London sojourn in the early 1970s, when he came up with the likes of The Bloodthirsty Butchers (1970) and The Rats Are Coming, The Werewolves Are Here (1972). Further up Dean Street, the actor Charles Laughton used to live in a flat – in what had been the house of Karl Marx – along with his wife, Elsa Lanchester, who played the twin roles of Mary Shelley and the shock-haired, hissing monster’s mate in Bride of Frankenstein (1935). On Wardour Street, the imposing art deco building standing at 113–117 is Hammer House, formerly the head office for the best-known makers of British horror, and if you walk towards Oxford Street, you’ll end up in Soho Square, the location of the offices of the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC). Jon Finch makes a telephone call from the square in Hitchcock’s Frenzy (1972). Murder, sex and film are all brought together in Michael Powell’s once-loathed, now-celebrated film Peeping Tom. It’s on the fringes of Soho that we first meet the sympathetic cameraman/killer Mark Lewis as he picks up a victim in Newman Passage, filming her as he does so. Powell shot some of the film in the suburb of Cricklewood, once the location of a film studio and just around the corner from the flat in Melrose Avenue where Nilsen killed a dozen of his victims before dismembering them and boiling, burning or burying them under the floorboards in his living room… Bound for the Lost Continent Until very recently, British horror cinema has been ignored and maligned, hidden away like the eponymous feral brother in the The Beast in the Cellar (1970). Even when it was celebrated, neglect was not far behind: David Pirie’s seminal study A Heritage of Horror (1973) was out of print for decades. What studies there were, even those which were avowedly encyclopaedic, have concentrated largely on the output of Hammer, the best- known producers of British horror. But recent years have seen a number of books of this once-despised tradition (see Boot 1996; Rigby 2000; Chibnall and Petley 2002) as well as a long overdue update of the Pirie book. The extremely influential central thesis of the latter is still relevant: 2 Frightmares v3.indd 2 28/02/2016 16:41 INTRODUCTION It certainly seems to be arguable on commercial, historical and artistic grounds that the horror genre, as it has been developed in this country by Hammer and its rivals, remains the only staple cinematic myth which Britain can properly claim its own, and which relates to it in the same way as the western relates to America. (2007 [1973]: xv) Julian Petley’s 1986 essay, ‘The Lost Continent’ (which takes its title and central metaphor from one of Hammer’s wackier effforts) reinforces Pirie’s argument, describing a neglected tradition of fantastic, horrific and sensational cinema which formed: An other, repressed side of British cinema, a dark disdained thread weaving the length and breadth of that cinema, crossing authorial and generic boundaries, sometimes almost entirely invisible, sometimes erupting explosively, always received critically with fear and disapproval. (1986: 98) This refusal to acknowledge this ‘other, repressed side’ is compounded by the dominance of certain forms of cinema which represent the ‘real’, the everyday, the naturalistic. For Petley, this: Vaunting and valorising of certain British films on account of their ‘realism’ entails, as its corollary… the dismissal and denigration of those films deemed un- or non-realist. (ibid.) This tendency to reject the kind of cinema which dwells in this Lost Continent, when combined with a very British kind of island mentality, has also led to the horrific and the sensational being not just sidelined but actively suppressed. It’s not for nothing that Mark Kermode has written of the ‘hundred-year terror’ that the British Board of Film Classification (nee Censors) has visited upon the horror genre (Kermode 2002: 22). Given this deep-seated and abiding suspicion of the popular and the fantastic, it comes as no surprise that both Pirie and Petley seek to locate Hammer et al in an illustrious literary tradition. For the former, the fact that so many British horror films ‘are derived… from literary sources’(2007: xv) is highly significant: The literary basis of the films is so striking that I make no apology for the literary orientation of this book; the film medium is not an extension of literature (or of anything else) but in this instance literary comparison becomes not only illuminating but essential. (ibid.) Petley, meanwhile, when observing the lengthy period it took for the genre to establish itself in the medium of film draws on that same literary tradition, noting how: For the country which produced Mary Shelley, Lord Byron, Bram Stoker, Anne Radcliffe, Charles Maturin, Matthew Lewis, M.R. James, Algernon Blackwood, William Hope Hodgson and William Beckford, Britain was peculiarly slow in developing the horror film and the whole area of fantasy cinema. (1986: 113) 3 Frightmares v3.indd 3 28/02/2016 16:41