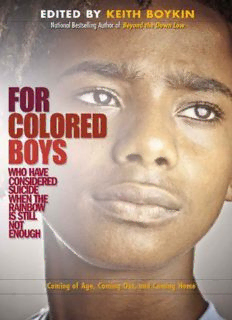

For Colored Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Still Not Enough: Coming of Age, Coming Out, and Coming Home PDF

Preview For Colored Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Still Not Enough: Coming of Age, Coming Out, and Coming Home

Copyright © 2012 by Keith Boykin, Contributors retain the rights to their individual pieces of work. Magnus Books An Imprint of Riverdale Avenue Books 5676 Riverside Drive, Suite 101 Riverdale, NY 10471 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, without permission in writing from the publisher. First Magnus Books edition 2012 Cover by: Linda Kosarin ISBN: 978-1-936833-97-9 www.riverdaleavebooks.com Submission Review Editors La Marr Jurelle Bruce Clay Cane Mark Corece Frank Roberts Contents Introduction GROWING PAINS Back to School - Craig Washington Guys and Dolls - Jarrett Neal Pop Quiz - Kevin E. Taylor Bathtubs and Hot Water - Shaun Lockhart Strange Fruit - Antonio Brown THE FAMILY THAT PREYS Teaspoons of December Alabama - Rodney Terich Leonard A House is Not a Home - Rob Smith Mother to Son - Chaz Barracks I'M COMING OUT! Pride - James Earl Hardy Age of Consent - Alphonso Morgan The Luckiest Gay Son in the World - David Bridgeforth When I Dare to Be Powerful - Keith Boykin FOR COLORED BOYS To Colored Boys Who Have Considered Suicide - Hassan Beyah Mariconcito - Emanuel Xavier Chicago - Phill Branch Better Days - Jamal Brown One Day a DJ Saved My Life - Jonathan Kidd WHEN THE RAINBOW IS NOT ENOUGH No Asians, Blacks, Fats, or Femmes - Indie Harper Alone, Outside - G. Winston James When the Strong Grow Weak - Kenyon Farrow FAITH UNDER FIRE The Holy Redeemer - Victor Yates Coventry, Christ, and Coming of Age - Topher Campbell Religious Zombies - Clay Cane Preacher's Kid - Nathan Hale Williams LOVE IS A BATTLEFIELD I Still Think of You - Jason Haas Bad Romance - Darian Aaron Afraid of My Own Reflection - Antron Reshaud Olukayode Just the Two of Us - Curtis Pate III Hey, You - Erick Johnson My Night with the Sun - Mark Corece Love Your Truth - B. Scott BOYS LIKE GIRLS The Night Diana Died - Daren J. Fleming Many Rivers to Cross - André St. Clair Thompson Becoming Jessica Wild - José David Sierra IN SICKNESS AND HEALTH Umm... Okay - Tim'm T. West Thank You, CNN - David Malebranche The Test - Charles Stephens The Voice - Ron Simmons It's Only Love that Gets You Through - Robert E. Penn POWER TO THE PEOPLE We Cannot Forget - Victor Yates Poetry of the Flesh - Lorenzo Herrera y Lozano Casualties of War - L. Michael Gipson How Do You Start a Revolution? - Keith Boykin Acknowledgments Contributors Introduction In the fall of 2010, eighteen-year-old Rutgers University student Tyler Clementi was secretly videotaped by his roommate during an intimate encounter with another man. On September 22, Clementi drove to the George Washington Bridge, got out of his car, and leapt to his death. On the same day, in a different part of the country, lawyers for a young black man named Jamal Parris walked into the DeKalb County Courthouse in Georgia and filed a lawsuit against Bishop Eddie Long of the New Birth Missionary Baptist Church, accusing the pastor of using his influence to coerce Parris into a sexual relationship. These two unrelated incidents revealed dramatic differences in the way our society responds to race and sexuality. The killing of unarmed teenager Trayvon Martin in February 2012 and the death of a Florida A&M drama major in November 2011 confirm this trend. Meanwhile, the abuse charges by Jamal Parris and several other young black men were met with attacks and criticism by members of Long’s church and other religious supporters who questioned the credibility of the accusers. Despite the media attention to the story in Atlanta, there was no real organized effort to protect young black men from harm or sexual abuse, no YouTube video campaign, and no support mechanisms put in place to provide counseling and assistance for others. It should come as no surprise to anyone who has followed the news that our society has a tendency to dismiss the grievous experiences of young men of color. A tragic shooting on a suburban campus, for example, provokes a sense of shock and outrage while similar tragedies at inner city schools often go ignored. Perhaps the best example may be the way in which society and the media dealt with several other youth suicides in the same time period as Clementi’s death. In April 2009, Carl Joseph Walker-Hoover, an eleven-year-old black student in Massachusetts, hanged himself in his bedroom. Carl was a young football player and Boy Scout who had endured months of harassment and anti-gay bullying. He was just one week shy of his twelfth birthday when he committed suicide. In the same month, another eleven-year-old, Jaheem Herrera of Atlanta, took his own life after suffering constant anti-gay bullying at his DeKalb County school. He too was African American. Then, in September 2010, the same month in which Tyler Clementi killed himself, nineteen-year-old Raymond Chase, a black openly gay college student studying culinary arts at Johnson & Wales University in Providence, Rhode Island, committed suicide by hanging himself in his dorm room. In the following month, a twenty-six-year-old black gay youth activist named Joseph Jefferson took his own life. Joseph had worked with HIV/AIDS charities and helped to promote black LGBT events. “I could not bear the burden of living as a gay man of color in a world grown cold and hateful towards those of us who live and love differently than the so-called ‘social mainstream,’” he wrote on his Facebook page the day he killed himself. Sadly, these suicides did not generate much attention in the mainstream media or action in the larger community. I was covering the 2010-midterm elections for CNBC when I first heard about Tyler Clementi and Raymond Chase and the other suicides. As I drove across the George Washington Bridge one night from Manhattan to the CNBC World Headquarters in New Jersey, I looked down over the bridge and imagined what it must have felt like to jump 212 feet into the raging Hudson River below. I’ve known friends who have committed or considered suicide, but I had never contemplated it for myself. That’s when I decided to put together this book. Despite the well-intentioned messaging in response to Clementi’s death, life doesn’t always “get better” anytime soon, especially for people of color who are disproportionately affected by many challenging socioeconomic conditions. When it came time to start this project, the title would prove obvious. In 1974, playwright Ntozake Shange published her famous choreopoem, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When The Rainbow Is Enuf, which later became the subject of a popular film in 2010. As young boys of color were literally committing suicide in the same year when the movie was released, it underscored that the LGBT community’s promise of the rainbow was clearly not enough for many to sustain themselves. To put together this book, I wondered what it would take for a young man to get to the point where he felt he had nothing left to live for. I didn’t have to wonder very long. A few days after we put out the call for submissions, I planned to ask a young friend to serve as an editor of the book. David, an Ivy League-educated black gay man, had worked with me on several projects in the past and had once served as my personal assistant as well. But before I could contact him with my request, I received a disturbing phone call from a mutual friend. I discovered that David had taken his own life. The police found a suicide note written on an envelope in David’s car. It simply said that he wanted to be cremated and buried next to his mother. He never explained what drove him to kill himself, but for some reason I always knew that he, like so many others, didn’t completely fit in with the rest of the crowd. That experience reminded me that men of color—especially gay men of color—must speak out and share our stories of how we have faced obstacles in our own lives. Many of us have endured and sometimes overcome experiences with racism, homophobia, abuse, molestation, violence, and disease. We’ve struggled with religion, self-acceptance, gender identity, love, relationships, and intimacy, and we’ve sometimes internalized the prejudices and biases directed against us. Our stories are rarely told, except in sensationalistic tones that demonize us as predators and villains. And, so, we must tell our own stories in a way that represents us as full human beings. I was fortunate to come out into a world where those stories were just starting to be told. While I was a student at Harvard in 1991, I came across a book called Brother To Brother: New Writings by Black Gay Men, edited by Essex Hemphill. I went to see Hemphill at a book reading event at nearby MIT, and his book quickly became a bible for me. But Hemphill, like many of the young black authors in his anthology, died of AIDS-related complications within a few years. That’s why so much of our history has disappeared. Back then there was no real treatment for AIDS. There were also no openly gay TV anchors like Don Lemon or comedians like Wanda Sykes, and E. Lynn Harris was just getting started as a novelist. And the idea of gay marriage was unthinkable even to gay people. There was no Internet, no hookup websites and no cell phone apps to connect you to the closest date. No one even had a cell phone back then. In the decades since Brother to Brother was published, we’ve elected our first black president, appointed the first Latina to the Supreme Court, repealed the ban on gays in the military, and developed life-saving treatments for people living with HIV/AIDS. At the same time, however, independent community bookstores have vanished, magazines and publications have gone out of business, and neighborhoods that once serviced the needs of minority communities have slowly disappeared. The world is changing rapidly, and so too is our literature. The diversity of this book reflects some of those changes. We received hundreds of submissions for this anthology, and many outstanding pieces could not be included. But this collection includes writers who are African American, Latino, Asian American, British, and Jamaican. Their ages range from their early twenties to their sixties,

Description: