Fighting the Greater Jihad PDF

Preview Fighting the Greater Jihad

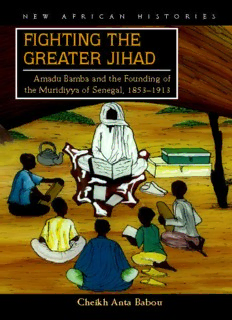

Fighting the Greater Jihad n e w a f r i c a n h i s to r i e s s e r i e s Series editors: Jean Allman and Allen Isaacman David William Cohen and E. S. Atieno Odhiambo, The Risks of Knowledge: Investigations into the Death of the Hon. Minister John Robert Ouko in Kenya, 1990 Belinda Bozzoli, Theatres of Struggle and the End of Apartheid Gary Kynoch, WeAre Fighting the World: A History of Marashea Gangs in South Africa, 1947–1999 Stephanie Newell, The Forger’s Tale: The Search for Odeziaku Jacob A. Tropp, Natures of Colonial Change: Environmental Relations in the Making of the Transkei Jan Bender Shetler, Imagining Serengeti: A History of Landscape Memory in Tanzania from Earliest Times to the Present Cheikh Anta Babou, Fighting the Greater Jihad: Amadu Bamba and the Founding of the Muridiyya in Senegal, 1853–1913 Fighting the Greater Jihad Amadu Bamba and the Founding of the Muridiyya of Senegal, 1853–1913 w Cheikh Anta Babou ohio university press athens Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701 www.ohio.edu/oupress ©2007 by Ohio University Press Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper ƒ™ 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 5 4 3 2 1 An earlier version of one section of chapter 4 appeared as “Educating the Murid: Theory and Practices of Education in Amadu Bamba’s Thought,”Journal of Reli- gion in Africa 33, no. 3 (2003): 310–27. An earlier version of chapter 7 appeared as “Contesting Space, Shaping Places: Making Room for the Muridiyya in Colonial Senegal, 1912–1945,”Journal of African History46, no. 3 (2005): 405–26. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Babou, Cheikh Anta Mbacké. Fighting the greater jihad : Amadu Bamba and the founding of the Muridiyya of Senegal, 1853–1913 / Cheikh Anta Babou. p.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8214-1765-2 (hc : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8214-1765-7 (hc : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8214-1766-9 (pb : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8214-1766-5 (pb : alk. paper) 1. Bamba, Ahmadu, 1852–1927. 2. Muridiyah—Senegal—Biography. 3. Islam and politics—Senegal—History.4. Islamic sects—Senegal. I. Title. BP80.B238B33 2007 297.4'8--dc22 2007023162 Contents List of Illustrations vii Preface ix List of Abbreviations xi Note on Orthography xiii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Islam, Society,and Power in the Wolof States 20 Chapter 2 The Mbakke: The Foundations of Family Traditions 33 Chapter 3 The Emergence of Amadu Bamba, 1853–95 51 Chapter 4 The Founding of the Muridiyya 77 Chapter 5 Murid Conflict with the French Colonial Administration, 1889–1902 115 Chapter 6 SlowPath toward Accommodation I The Time of Rapprochement 141 Chapter 7 Slow Path toward Accommodation II Making Murid Space in Colonial Bawol 162 Conclusion 175 Appendix 1 IjaazaDelivered to Momar A. Sali by Samba Tukuloor Ka 185 Appendix 2 Sharifian Genealogy of Amadu Bamba from His Mother’s Side 187 v Appendix 3 Amadu Bamba’s Sons and Daughters and Their Mothers 189 Appendix 4 List of the Transmitters of the Qadiriyya wirdWhom Amadu Praises in His Poem “Silsilat ul Qadiriyya” 191 Notes 193 Bibliography 263 Index 285 vi w Contents Illustrations map Important places in Amadu Bamba’slife xiv figures Figure 2.1 Maaram’s sons and daughters 35 Figure 2.2 The Mbakke and Sy families 37 Figure 2.3 The Mbakke and Jakhate families 38 Figure 2.4 Momar Anta Sali’s sons and their mothers 46 Figure 3.1 Amadu Bamba’s paternal and maternal lineages 53 plates Following pages 140 Plate 1. Amadu Bamba’sarrival in the port of Dakar on his return from exile in Gabon Plate 2. Amadu Bamba teaching disciples in front of his house Plate 3. The trial of Amadu Bamba Plate 4. Homecoming celebration in Daaru Salaam Plate 5. Sokhna Njakhat Sylla, a wife of Amadu Bamba Plate 6. Cell in the basement of the governor-general’s palace where Amadu Bamba was kept in custody while awaiting trial Plate 7. Mausoleum of Jaara Buso, Amadu Bamba’s mother, in Porokhaan Plate 8. Gigis tree in Porokhaan where Amadu Bamba’s father, Momar Anta Sali, taught his disciples vii Plate 9. Mosque of Diourbel Plate 10. Mosque of Tuubaa Plate 11. Murid businesses in “Little Senegal,” Harlem, New York City Plate 12. Murids marching during the annual celebration of Amadu Bamba Day (July 28) in New York City Plate 13. The late Cheikh Murtala Mbakke, youngest son of Amadu Bamba, and Mayor David Dinkins at New York City Hall Plate 14. William Ponty, governor-general of French West Africa (1908–15) Plate 15. Amadu Bamba Plate 16. One of the four small minarets of the great mosque of Tuubaa Plate 17. The well of mercy, dug at the instruction of Amadu Bamba in Tuubaa Plate 18. Mihrab,or prayer niche, of the mosque of Tuubaa viii w Illustrations Preface This book concerns the genesis and development of the Muridiyya of Sene- gal, and especially the role of education in its founding. Previous works have shed light on the political and economic dimensions of the Murid tariqa,and scholars have expounded on its remarkable capacity to adapt Islam to the local cultural context. This research draws on the abundant but largely un- tapped Murid internal oral, written, and iconographic sources, as well as archival data, to offer a comprehensive reconstruction of the history of the Muridiyya that pays special attention to the impact of the often overlooked Murid sheikhs’ and disciples’ voices. The book focuses on the early years of thetariqa’sfounding, but the discussion of issues such as ethics, educational practices, sacred space, and memory provides clues for understanding the un- usual ability of the Murid order to maintain cohesion and continuity across space and time. Iwish to acknowledge the assistance and support provided by several insti- tutions. A fellowship from the Rockefeller Foundation’s African Dissertation Internship Awards funded one year of field and archival research in Senegal. A merit fellowship from the College of Arts and Letters at Michigan State University made possible a semester of leave devoted to writing. I have bene- fited from the support of the West African Research Center in Dakar, which graciously offered office and computer facilities during my fieldwork in Sene- gal. I am also grateful to Saliou Mbaye, Mamadou Ndiaye, Babacar Ndiaye and all of the staff of the National Archives in Senegal. For their help, I would like to thank Al Hajj Mbakke, former head of the library Sheikh ul Khadim in Tuubaa; Serigne Mustafa Jatara, his successor; and their assistants. Gora Dia and his colleagues at the library of Institut Fondamental d’Afrique Noire (IFAN) have aided greatly. I thank Jean Pierre Diouf and Abou Moussa Ndongo at the documentation center of the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) for their assistance. Iam particularly grateful to my hosts, colleagues, and informants in Sene- gal. My friends Aida and Grégoire Lawson welcomed me into their beautiful ix

Description: