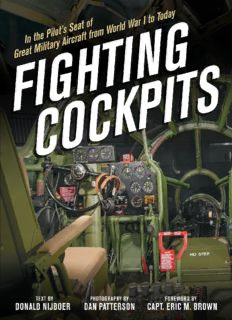

Fighting Cockpits: In the Pilot’s Seat of Great Military Aircraft from World War I to Today PDF

Preview Fighting Cockpits: In the Pilot’s Seat of Great Military Aircraft from World War I to Today

FIGHTING COCKPITS In the Pilot’s Seat of Great Military Aircraft from World War I to Today DONALD NIJBOER PHOTOGRAPHY BY DAN PATTERSON CONTENTS FOREWORD: By Eric Brown, CBE, DSC, AFC, Hon FRAeS, RN Former Chief Naval Test Pilot, RAE Farnborough INTRODUCTION 1 WORLD WAR I WIND IN THE WIRES Nieuport 28 Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5 Bristol F.2B Fokker Dr.I Sopwith Camel Sopwith Triplane AEG G.IV SPAD VII Halberstadt CL.IV Fokker D.VII 2 BETWEEN THE WARS THE RISE OF THE MONOPLANE Martin MB-2 Hawker Hind Fiat CR.32 Boeing P-26 Peashooter Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk Vought SB2U Vindicator Westland Lysander PZL P.11 3 WORLD WAR II DEATH AT 30,000 FEET Supermarine Spitfire Messerschmitt Bf 109 Republic P-47 Thunderbolt North American P-51 Mustang Handley Page Halifax Vickers Wellington Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Würger Fairey Firefly Fiat CR.42 Ilyushin Il-2 Šturmovík Heinkel He 219 Uhu Kawasaki Ki-45 Toryuū Curtiss SB2C Helldiver Northrop P-61 Black Widow Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress Boeing B-29 Superfortress Dornier Do 335 Pfeil Messerschmitt Me 262 Schwalbe Arado Ar 234 Blitz 4 COLD WAR TO THE PRESENT MUTUALLY ASSURED DESTRUCTION North American F-86 Sabre Boeing B-52 Stratofortress Grumman A-6 Intruder General Dynamics F-111 Aardvark Hawker Siddeley Harrier McDonnell Douglas/Boeing F-15 Eagle Grumman F-14 Tomcat Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II General Dynamics/Lockheed Martin F-16 Fighting Falcon Mikoyan MiG-29 Rockwell B-1 Lancer Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter BIBLIOGRAPHY ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INDEX FOREWORD The first time I approach an aircraft I am about to fly, I size it up by observing its beauty of line to assess aerodynamic cleanliness, then its “sit” to judge if its balance seems right, and next its engine(s) layout to consider if there could be a likelihood of torque or asymmetry problems. However, this is just a visual exercise—my mind is really full of anticipation for what the cockpit will be like, for this is the nerve center of any flight that is to be undertaken. As a pilot, I look for an “all-round” view: comfortable and easy access to vital controls (control column, rudder pedals, throttle[s], fuel cocks, propeller feathering buttons), ejection methods, and an all-weather instrument panel. These may sound like obvious requirements, but they are by no means always met in the complexity of modern cockpits. Ergonomics is the study of the application of logic to environmental engineering and had its beginnings in World War II. I remember well the first such practical examples I saw were Germany’s Heinkel 219 night fighter and United Kingdom’s Martin Baker 5 prototype fighter, but the life of aircraft designers was easier in those far-off days. The modern designer, however, does have the flexibility of computerization to aid in this increasingly difficult task. In examining the history of cockpit development, Donald Nijboer has divided aviation into four logical eras, and provides a chapter on each of beautifully written and astute observations on almost every aspect of flight and its incredible progress over the last one hundred years. Nijboer is a master of the rare subject of cockpits, and his cooperation with Dan Patterson, one of the world’s leading aviation photographers, guarantees an end product of such quality it will be an asset to grace any aviation buff’s bookshelves. Eric Brown, CBE, DSC, AFC, Hon FRAeS, RN Former Chief Naval Test Pilot, RAE Farnborough Sublieutenant Eric Brown in the cockpit of his Martlet Mk I (F4F Wildcat) aboard the Royal Navy’s first escort carrier, HMS Empire Audacity, fall 1941. During the course of three-plus decades, Brown flew 490 different types of aircraft, including almost every major (and most minor) combat aircraft of World War II. He also holds the world record for carrier landings—2,407. Author collection INTRODUCTION The origins for the term “cockpit” are unknown. Some say it was taken from the nautical term for a depression in the deck of a ship for the tiller and helmsman. Another source comes from the bloody sport of cockfighting. According to Jane’s Aerospace Dictionary the cockpit is defined as “space occupied by pilot or other occupants, especially if open at the top. Preferably restricted to small aircraft in which the occupants cannot move in their seat.” That rather dry description doesn’t come close to describing the place from which the fighting cocks of the aviation world waged their vicious battles. The fighting cockpit was never designed for comfort or pleasure. From the canvas and wood structures of World War I to the high-tech all-glass cockpits of today, the cockpit remains a solitary, mysterious, and dangerous place. From the very beginning of air combat, the cockpit was one of the last parts of the aircraft to which designers turned their focus. Their concerns were engine power, armament, and aerodynamics. The pilot had to go somewhere and it was almost always over the center of gravity. For World War I pilots, the cockpit was composed of nothing more than a wicker seat, canvas sides, a control column, rudder pedals, one or two instruments, and a machine gun. It was a cold, noisy, unforgiving space. Here, the pilot’s biggest fear was being burned alive. Many carried a pistol, and parachutes weren’t used until the end of the war and then only by the Germans. The 1930s saw the advent of the all-metal monoplane fighter and bomber. With its enclosed cockpit pilots reached new speeds and heights unimagined just a few short years before. They were also in greater danger—the cockpit was a more cluttered space with myriad instruments and controls. Little thought was given as to how a good functioning cockpit should work. Pulling the wrong lever or bumping a switch often meant a crash landing or worse. During World War II the cockpit had developed to some degree, but most of the designs were still from the 1930s. A Battle of Britain Spitfire pilot would find few surprises in a 1944 P-51 or Tempest. Fighter pilots have often described “bonding” with their aircraft—sitting snuggly in the cockpit and having the feeling of being one with their fighter. That snugness, however, had more to do with the structure of the aircraft and not the cockpit design. A streamlined Spitfire with its liquid-cooled Merlin had a slender fuselage and thus a tight cockpit. The P-47 Thunderbolt, with its giant R- 2800 Double Wasp radial engine, had a more commodious front office. 2800 Double Wasp radial engine, had a more commodious front office. The advent of jet combat, with the introduction of the Gloster Meteor Mk I and Messerschmitt Me 262 in 1944, ushered in a new era of military aviation. From the 1950s onward aircraft performance improved at a rapid rate and aircraft systems kept pace by becoming more complex. A pilot’s workload increased and multirole aircraft only complicated the situation. Little thought was initially given to ensure the pilot/machine interface was properly designed. Accident rates were high, and most were attributed to pilot error. Years would pass before designers turned their attention to the idea that pilots and aircrew had to be aware at all times of what their aircraft was doing both inside and outside the cockpit, or that the instruments and controls inside had to be logically arranged. Only then could flight and engine information be easily and quickly accessed, allowing for sensible and rapid decisions. Today’s modern fighter cockpit is a marvel of technology. Innovations like the heads-up display (HUD), multifunction display (MFD), hands-on throttle and stick (HOTAS), and forward-looking infrared (FLIR) have made the cockpit easier to fly and fight in. Digital computers do most of the flying. As F-22 pilot Lt. Col. Clayton Percle explains, “You’re basically a voting member. You don’t have the final decision.” This book is divided into four distinct periods of aviation, and each chapter introduction describes the evolution of the cockpit. Through Dan Patterson’s amazing photographs we get to see this transformation up close, from the Blériot to the F-35. We also hear firsthand accounts from the “world’s greatest pilot,” Capt. Eric Brown RN (Ret.), as well as from combat veterans, test pilots, instructors, and current warbird pilots who describe what it’s like to be in the cockpits of these amazing aircraft. The result is a rare intimate glimpse of what it must have been like to fly in some of the most feared and famous combat aircraft ever built. CHAPTER ONE: WORLD WAR I WIND IN THE WIRES On August 4, 1914, German troops set foot on Belgian soil. Treaty-bound France, Britain, Italy, Austria, and Russia were irrevocably committed, and all of Europe was officially at war. It would be a war of extremes—of mud, mass slaughter, and stalemate; of technological marvels, and of the birth of a new type of warrior. Barely eleven years after the Wright Brothers took their first flight, this new war would take to the skies. Army commanders on both sides believed the coming confrontation would be a land campaign. Air power, still an unknown, would play a minor role at best. Early experiments in 1910 had proven that the best role for the airplane would be reconnaissance. French army maneuvers in 1911 consistently showed that airplanes could locate enemy troops some 37 miles (60 kilometers) away. After every war soldiers of all stripes disparage the generals and politicians for their lack of foresight and inability to properly prepare for the next war. The newly minted airmen of World War I drew especially bitter pleasure from this pastime. Often-repeated stories focused their venom on the great men who had dismissed the importance of the aeroplane. Britain’s generals Sir William Nicholson and Sir Douglas Haig suggested before the war that aircraft would never be of any use to the army. In truth, however, the major world powers had already begun to build up their air forces with remarkable rapidity shortly before the opening of hostilities. An S.E.5a cockpit section revealed. This simple, wire-braced, box-girder wooden construction was typical for a World War I scout. In August 1914 the nations of Europe mobilized more than six million men for battle. That total, however, included fewer than two thousand pilots and one thousand aircraft. The fragile wood-and-canvas open-cockpit planes that dominated both sides at the beginning of the war were all spectacularly slow. The Blériot XI, made famous by Louis Blériot when he flew across the English Channel in 1909, equipped seven British, eight French, and six Italian squadrons at the outbreak of war. For all its fragility, the Blériot XI was leading-edge technology. Cockpit “instrumentation” consisted of a watch and a map of the flight route rolled onto a scroll. Airspeed and altitude were left to the pilot’s

Description: