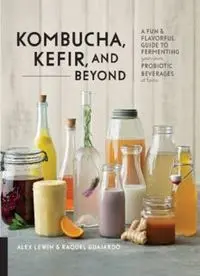

Table Of ContentKOMBUCHA, KEFIR, AND

BEYOND

A FUN & FLAVORFUL GUIDE TO FERMENTING

your own

PROBIOTIC BEVERAGES

at home

ALEX LEWIN & RAQUEL GUAJARDO

CONTENTS

PREFACES

1 WHY FERMENT YOUR DRINKS?

2 OUR CULTURED HISTORY

3 FERMENTATION, SCIENCE, AND HEALTH

4 BEFORE YOU START

5 FIVE-MINUTE RECIPES

6 STARTERS, MASTER RECIPES, AND GENERAL PRINCIPLES

7 KOMBUCHA AND JUN

8 VEGETABLE DRINKS

9 SODAS

10 BEERS, GRAINS, AND ROOTS

11 WINES, CIDERS, AND FRUITS (AND VINEGAR!)

12 MEXICAN PRE-HISPANIC DRINKS

13 FERMENTED COCKTAILS

RESOURCES

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

RECIPE DIRECTORY

INDEX

PREFACES

RAQUEL GUAJARDO

I WAS BORN and raised in Monterrey, Nuevo León, an industrial town surrounded

by mountains in the north of Mexico that is well known for its carne asada,

cabrito, tortilla de harina, and beer. As a proud regiomontana, I have always

loved beer, but I didn’t associate it with fermentation, and never in my wildest

dreams could I have imagined myself brewing my own.

For me, fermentation started in Seattle, Washington, during a Real Food

Cooking Course taught by Monica Corrado. Among other things, she taught me

how to make sauerkraut and the principles of fermentation. She recommended

the book Wild Fermentation by Sandor Katz, and soon I was hooked on

everything fermented.

Then, two years ago, I invited Sandor to teach a workshop in Monterrey. More

people got hooked, and I got inspired to experiment and come up with my own

recipes.

Then I invited Alex to teach another fermentation workshop in Monterrey, on

kimchi and the science of fermentation. During his stay, he tasted a couple of my

fermented beverages, and I am pretty sure he enjoyed them. After all, the idea

for this book was born in my kitchen as we drank pulque and tepache.

ALEX LEWIN

I GREW UP in the Northeast of the U.S., in New York, Connecticut, and

Massachusetts. I started thinking and reading about food and health when I was

in my 20s. One book would say one thing, another book would say something

different and incompatible, and both would have good justifications for what

they said. I was curious by nature, and at the time I hated unsolved mysteries, so

I started reading more. This led me on a path of discovery informed by Andrew

Weil, Sandor Katz, Sally Fallon, the Institute for Integrative Nutrition, the

Cambridge School of Culinary Arts, and many more. In fact, my views are

informed by almost everyone I talk with about health and food. And I have made

my peace with unsolved mysteries—there will always be some things that we

don’t know, and I’m okay with that. Fermentation, especially with wild starters,

depending as it does on invisible forces and serendipity, is a great stage on which

to dance with the unknown.

I speak for both Raquel and myself when I say that we’ve enjoyed being

learning partners together. Our skills and perspectives and communities are

similar in so many ways, and complementary in so many others; working

together has been fun and enlightening.

We are all stronger when we work together, embracing difference, diversity,

the unfamiliar, and the unknown. Do not let misguided demagogues suggest

otherwise.

We hope that you enjoy this book that we’ve brewed up for you. Salud!

CHAPTER ONE

WHY FERMENT YOUR DRINKS?

We are in the midst of a health crisis—or, to put it

another way, a disease crisis. For proof, just turn on the

television. You’ll be exhorted to buy diabetes

maintenance equipment; cholesterol-lowering drugs

with significant side effects; digestive nostrums that

blunt unpleasant symptoms without addressing

underlying causes; allergy pills that suppress the

immune system; painkillers; and more.

The interspersed commercials are for sugary

drinks, junk food, and toxic personal care

and cleaning products, the use of which

likely contributes to conditions such as

diabetes, cardiovascular disease, digestive

problems, and allergies. Sound familiar? It doesn’t seem like this is a complete

coincidence.

Love it or hate it, advertising is a reliable bellwether: The commercials we see

are the ones that sell product and make money. Super Bowl commercials, for

example, are the caviar of the domestic advertising world. Guaranteed millions

of viewers, these ads cost 10 million dollars per minute. Yet during the 2016

Super Bowl, we saw an ad for a drug to address a very specific malady that

many of us had never considered: opioid-induced constipation. Opioids are

opium-derived and opium-related drugs, including a long list of prescription

painkillers and street drugs. If we were a nation of healthy people, we’d be

seeing different commercials.

Mexico finds itself in the same boat as the United States. It is one of the

world’s most obese countries with one of the highest infant diabetes rates.

American fast food chains and supermarkets have been crowding out mercados,

where fresh seasonal food used to be found. For the younger generations, buying

American fast food is part of the modern way of life, cool and hip, like having a

cell phone, whereas the typical grandma foods such as pozole, tamales, and mole

are old-fashioned. Even the tortilla, the hallmark of Mexican food, has changed

for the worse, and sadly, traditional tortillerías are disappearing.

As the United States goes, so go not only her American neighbors, but much

of the world. With the expansion of markets for big-business food and tobacco

products comes diabetes, heart disease, obesity, cancer, and chronic digestive

and immune system dysfunction. And these maladies create new markets for

pharmaceutical products.

Are drugs really the best way to break this cycle? Maybe fermented beverages

can help.

WHAT IS FERMENTATION, ANYWAY?

Fermentation is the transformation of food through the action of microbes.

Microbes are microscopic life forms, including bacteria, yeasts, and molds.

(Viruses are sometimes considered microbes. They have no metabolism, so they

aren’t direct agents of fermentation, and they won’t be discussed here.) Via

chemical reactions, these microbes transform carbohydrates (sugars and

starches) into acids, alcohols, and gases. Along the way, small but useful

amounts of vitamins and enzymes are created too.

Digestion refers to processes in living organisms that break down food into

various components. Digestion is generally accelerated by heat and catalyzed by

special proteins called enzymes. Enzymes are employed by all life forms, from

microbes to mammals. In fact, it turns out that many of the same enzymes used

by microbes are also found in the human digestive tract. This is not a

coincidence—many of our gut enzymes are created by microbes that live there.

These enzymes play a crucial role in human digestion.

These enzymes also play a crucial role in fermentation, which happens when

microbes use them to start breaking down food. These microbes are effectively

predigesting our fermenting food, in some of the same ways that we ourselves

digest food inside our bodies, using some of the same enzymes. So when we eat

fermented foods, we are getting ahead of the game; these foods are easier for our

bodies to digest. This may help us to better assimilate important nutrients from

the food—we have more time to break down compounds that could inhibit

nutrient uptake. It may also reduce difficult-to-digest and inflammatory

compounds, so we face fewer signs of digestive difficulties such as gas, bloating,

acid reflux, and heartburn. This helps us to mitigate, avoid, and sometimes

reverse chronic long-term digestive diseases.

As by-products of metabolism and digestion, some microbes create

meaningful amounts of B and C

vitamins. Some microbes also create

other, more obscure human

nutrients, including some whose

functions we are still learning about

and some that we may never know

about or understand. Additionally,

many of the products of

fermentation promote health, stave

off disease, and/or actively reverse

some types of health problems in

humans and other bigger creatures.

This is particularly the case when

small amounts of minerals or

organic materials, such as herbs, are

included in the fermenting process.

We are only beginning to understand

some of the substances and

mechanisms involved.

EAT REAL FOODS

Food science does not necessarily prioritize the discovery of new food nutrients

—there’s much more incentive to invent new industrial processes that save time

and money, or to create new flavorings for potato chips and fast food. From the

point of view of human health, food science advances slowly, sometimes taking

two steps forward and one step back. Unfortunately, that means the messages

that reach consumers about what they should or shouldn’t eat may not be

focused on what would help them maintain robust health.

Because food science isn’t focused on nutrition, it’s worth our while to seek

out real foods—foods that are close in form to how they occur in nature,

processed in the home kitchen, with trace compounds intact. Industrially

processed foods almost always lose nutritional value during processing; even if

they look okay on paper, they are often stripped of poorly understood or

unknown trace compounds. Their production process serves the food producers

first and the public second or third or not at all.

Consider the story of Soylent: In 2013, a pair of young entrepreneurs were

creating tech products that they hoped would change the world. Because they

wanted to maximize the time they spent working on their projects, they were

frustrated that it took so long to select, procure, prepare, and eat food. So they