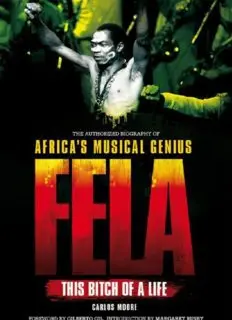

Fela - This Bitch of A Life PDF

Preview Fela - This Bitch of A Life

Copyright © 2009 by Carlos Moore Forward © 2009 by Gilberto Gil Introduction © by Margaret Busby Original © 1982 by Carlos Moore as Fela, Fela: cette putain de vie (Paris: Khartala). Published in English in 1982 as Fela, Fela: This Bitch Of A Life (London: Allison and Busby). English translation © 1982 by Allison and Busby This edition © 2011 Omnibus Press (A Division of Music Sales Limited, 14-15 Berners Street, London W1T 3LJ) ISBN: 978-0-85712-589-7 Cover designed by Fresh Lemon Photographs © by individual photographers (André Bernabé, Chico, Donald Cox, Bernard Matussière, Raymond Sardaby) and Fela Kuti, Fela Kuti Collection. The Author hereby asserts his / her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages. Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of the photographs in this book, but one or two were unreachable. We would be grateful if the photographers concerned would contact us. A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library. For all your musical needs including instruments, sheet music and accessories, visit www.musicroom.com For on-demand sheet music straight to your home printer, visit www.sheetmusicdirect.com Contents Information Page Foreword by Gilberto Gil A Note from the Author Introduction by Margaret Busby Discography 1 Abiku: The Twice-Born 2 Three Thousand Strokes 3 Funmilayo: “Give Me Happiness” 4 Hello, Life! Goodbye, Daudu 5 J.K. Braimah: My Man Fela 6 A Long Way From Home 7 Remi: The One with the Beautiful Face 8 From Highlife Jazz to Afro-Beat: Getting My Shit Together 9 Lost and Found in the Jungle of Skyscrapers 10 Sandra: Woman, Lover, Friend 11 The Birth of Kalakuta Republic 12 J.K. Braimah: The Reunion 13 Alagbon Close: “Expensive Shit”, “Kalakuta Show”, “Confusion” 14 From Adewusi to Obasanjo 15 The Sack of Kalakuta: “Sorrow, Tears and Blood”, “Unknown Soldier”, “Stalemate” 16 Shuffering and Shmiling: “ITT”, “Authority Stealing” 17 Why I Was Deported from Ghana: “Zombie”, “Mr Follow Follow”, “Fear Not for Man”, “V.I.P.” 18 My Second Marriage 19 My Queens 20 What Woman is to Me: “Mattress”, “Lady” 21 My Mother’s Death: “Coffin for Head of State” 22 Men, Gods and Spirits 23 This Motherfucking Life Epilogue: Rebel with a Cause Foreword Gilberto Gil Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, August 18, 2008 Africa, with her many peoples and cultures, is where the tragicomedy of the human race first fatefully presented itself, wearing a mask at once beautiful and horrendous. The Motherland, the cradle of civilization, acknowledged as the original birthplace of us all, where the body and soul of mankind sank earliest roots into the soil—Africa is, confoundingly, also the most reviled, wounded, and disinherited of continents. Africa, treasure trove of fabulous material and symbolic riches that throughout history have succored the rest of the world, is yet the terrain that witnesses the greatest hunger ever, for bread and for justice. This is the scenario into which Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, Africa’s most recent genius, emerged and struggled. I was privileged to meet Fela in 1977 in his own musical kingdom, the Shrine, a club located in one of Lagos’s lively working-class neighborhoods. It was during the Second Festival of Black and African Arts and Culture (FESTAC), and on that evening the great Stevie Wonder was also visiting. Fela was the brilliant incarnation of Africa’s tragic dimension. He was an authentic contemporary African hero whose genius was to make his scream heard in every corner of the globe. Through his art, his wisdom, his politics, his formidable vigor and love of life, he managed to rend the stubborn veil that marginalizes “Otherness.” Deeply torn between the imperative of rejecting a legacy of subordination and the need to affirm a new libertarian future for his land and people, Fela ended up creating a body of work that is incomparable in terms of international popular music that expresses the cosmopolitan—and “cosmopolitical”—spirit of the second half of the twentieth century. Fela was possessed by an apocalyptic vision, wherein he saw how tall were the walls that had to be broken down. Thus, he engaged in a messianic rebellion. He was enthralled by the haunting lamentations that emerged from the diaspora of uprooted black slaves, reminding him of his own outraged sense of deracination in his native Africa—a land increasingly usurped by neocolonial self-interest. He was divided between the awareness that a universal future for all mankind was inevitable and the awareness that there was danger in denying Africa its own place in that future. Therefore he determined to rescue, both for his own people and for the world, the wise traditions of tribal Africa, having in mind that we might one day constitute a global tribe. Arming himself with a Saxon horn—a saxophone—Fela made music that harked back to days of yore, when his forebears were warriors and cattle herders. Yet putting into the balance his virtuoso improvisation, his poetic outbursts, he made everyone swing: in the Shrine, in the whole of Lagos, in every reservation, in every shantytown, in every township of the black planet. Today, some time after his passing, we are at a juncture at which we recognize and acknowledge Fela’s work. But we must confer another form of acknowledgment, one that goes beyond the careful, reverential attention that, increasingly, is afforded his music—an acknowledgment in a wider intellectual sense: one rooted in a careful analytical interpretation of what Fela and his work stood for. This book is among those that are aiming to fulfill that mandate. At a time when, all over the world, we are engaged in the huge and (who knows?) perhaps final effort to establish a viable humanist legacy for the generations still to come—in an era that I may call posthuman—it is indispensable to be able to rely on books that bestow on those efforts a true dimension of legacy. We need books that will tell us, now and here, and that later on will also tell the builders of posthumankind, about those notable men and women of our recent past, such as Fela Anikulapo-Kuti. We need to know who they were and what they were about and how they have enriched us. Translated from the Portuguese by Tereza Burmeister A Note from the Author Originally published in France in 1982 as Cette putain de vie (This Bitch of a Life), this book was born of a deep friendship with Fela and could not have been written in the first person without his unreserved trust. He never intruded in the work and allowed me full access to his personal files and domestic intimacy. I thank him; his senior wife, the late Remi Taylor; his cowives; and those members of his organization who assisted me in gathering the material for the book: J. K. Braimah, Mabinuori Kayode Idowu (aka ID), Durotimi Ikujenyo (aka Duro), and bandleader Lekan Animashaun. I am also grateful to Sandra Izsadore, Fela’s longtime friend, for her generous assistance. Writing the life story of someone else in the first person, then translating it into another language, are tricky and perilous tasks. I succeeded only thanks to Shawna Davis, who transcribed and edited the more than fifteen hours of tape- recorded interviews that served as the building blocks for the original version, then translated the manuscript into English. Her involvement was particularly important in the two opening chapters, “Abiku” and “Three Thousand Strokes,” and she contributed the descriptive biographical presentations of all those interviewed, as well as the general introduction to chapter 19, “My Queens” (where for the first time Fela’s wives expressed themselves). Without Shawna’s rewriting and translation skills, and keen eye for the artistic, Fela: This Bitch of a Life would have been a much different and certainly less attractive book. My debt to her is immense. Gratitude is also due to Nayede Thompson, who assisted Shawna with the transcription and early drafts. I am beholden to the late Ellen Wright—former literary agent and widow of Richard Wright—for having read the original manuscript and made pertinent suggestions, as did Marcia Lord, whose feedback was greatly valued. In addition, I acknowledge the generous assistance of André Bernabé, Heriberto Cuadrado Cogollo, and Donald Cox, whose photos, drawings, and newspaper collages helped create the proper mood for Fela’s story. This book owes a lot to Margaret Busby, who published the first English edition of the book in 1982. Befittingly, twenty-seven years later she has written the introduction to this new edition. I thank her dearly. I am especially grateful to Gilberto Gil for undertaking to write the foreword and to Stevie Wonder, Hugh Masekela, Randy Weston, and Femi Kuti for their commentaries. My literary agent, Janell Agyeman, and Lawrence Hill Books senior editor Susan Bradanini Betz worked hard toward the agreement that has finally made Fela’s life story, told in his own words, available to the public once more, and for the first time in the United States.