Father Elijah: An Apocalypse PDF

Preview Father Elijah: An Apocalypse

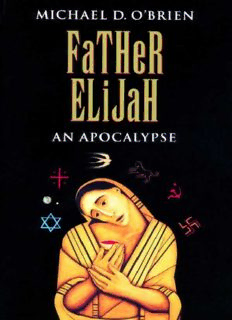

FATHER ELIJAH An Apocalypse MICHAEL D. O’BRIEN FATHER ELIJAH An Apocalypse IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO Cover art by Michael D. O’Brien David Schäfer’s Vision Cover design by Roxanne Mei Lum © 1996 Ignatius Press, San Francisco All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89870-690-1 (PB) ISBN 978-0-89870-580-5 (HB) ISBN 978-1-68149-172-1 (EB) Library of Congress catalogue number 95-79950 Printed in the United States of America Awake, and strengthen what remains and is on the point of death. . . . (Revelation 3:2) Contents Acknowledgments Introduction 1. Carmel 2. Rome 3. The Vatican 4. Assisi 5. Ruth 6. Naples 7. Isola di Capri 8. Rome 9. Rome 10. Warsaw 11. The Confession 12. Another Confession 13. The Conference 14. Rome 15. Rome 16. Foligno 17. Rome 18. Advent 19. In Pectore 20. Capri 21. Panaya Kapulu 22. Apokalypsis Endnotes Acknowledgments I am indebted to the Polish Canadian poet Christopher Zakrzewski for his translations of The Crimean Sonnets by Adam Mickiewicz, for permission to quote from them in Father Elijah, and for his editorial assistance. I am also most grateful to Marc Sebanc, translator, essayist, and novelist, for his wise insights and honesty. Above all, I wish to thank my wife, Sheila, whose editorial sense is unsurpassed, and whose patience as I stare glassy-eyed over many a meal will one day be rewarded. Introduction An apocalypse is a work of literature dealing with the end of human history. For millennia apocalypses of various sorts have arisen throughout the world in the cultural life of many peoples and religions. They are generated by philosophical speculation, by visions of the future, or by inarticulate longings and apprehensions, and not infrequently by the abiding human passion for what J. R. R. Tolkien called “sub-creation”. These poems, epics, fantasies, myths, and prophetic works bear a common witness to man’s transient state upon the earth. Man is a stranger and sojourner. His existence is inexpressibly beautiful—and dangerous. It is fraught with mysteries that beg to be deciphered. The Greek word apokalypsis means an uncovering, or revealing. Through such revelations man gazes into the panorama of human history in search of the key to his identity, in search of permanence and completion. Perhaps the worst of the “demythologizing” so endemic to our times is the message that the stories of the Christian Faith are merely our version of universal “myths”. It is suggested that many cultures have produced tales about a hero who is killed and then returns to life; many more have imagined a cataclysm that will occur at the end of history. G. K. Chesterton once wrote that the demythologizers’ position really adds up to this: since a truth has impressed itself deeply in the imagination of a vast number of ancient peoples, therefore it simply cannot be true. He pointed out that the demythologizer has failed to examine the most important consideration of all: that people of various times and places may have been informed at an intuitive level of actual events that would one day take place in history; that in their inner longings there was a glimmer of light, a presentiment, a yearning forward through the medium of art toward the fullness of Truth that would one day be made flesh in the Incarnation. Saint John’s Revelation is an apocalypse of a higher order. It is genuine prophecy in the sense that it is not merely a work of foretelling, but is a communication from the Lord of history Himself. It is an exhortation, an encouragement, a teaching vehicle, and a vision of actual events that will one day occur. As the drama of our century speeds toward some unknown climax, numerous speculations arise and new attention is given to John’s Apocalypse, stimulating a plethora of interpretation. One school of thought has it that the book refers solely to John’s own time; another asserts that it is exclusively a meditation on the end of things in some indeterminate future; still another believes that the book is a map of the Church’s history, unfolded in seven major epochs. A fourth interpretation, one favored by most of the Church Fathers, holds that it is a theological vision of a vast spiritual landscape, containing descriptions of the situation of the Church in John’s own time, and also the events that are to unfold at the end of time. For John, the “end times” begin with the Incarnation of Christ into the world, and there remains only a last battle through which the Church must pass. This, in my view, is the fullest and best interpretation, and it is the one I have followed in Father Elijah. The reader will encounter here an apocalypse in the old literary sense, but one that was written in the light of Christian revelation. It is a speculation, a work of fiction. It does not attempt to predict certain details of the final Apocalypse so much as to ask how human personality would respond under conditions of intolerable tension, in a moral climate that grows steadily chillier, in a spiritual state of constantly shifting horizons. The near future holds for us many possible variations on the apocalyptic theme, some more dire than others. I have presented only one scenario. And yet, the central character is plunged into a dilemma that would face him in any apocalypse. He finds himself within the events that are unfolding, and thus he is faced with the problem of perception: how to see the hidden structure of his chaotic times, how to step outside it and to view it objectively while remaining within it as a participant, as an agent for the good. The reader should be forewarned that this book is a novel of ideas. It does not proceed at the addictive pace of a television micro-drama, nor does it offer simplistic resolutions and false piety. It offers the Cross. It bears witness, I hope, to the ultimate victory of light.

Description: