Fanny Hill in Bombay: The Making and Unmaking of John Cleland PDF

Preview Fanny Hill in Bombay: The Making and Unmaking of John Cleland

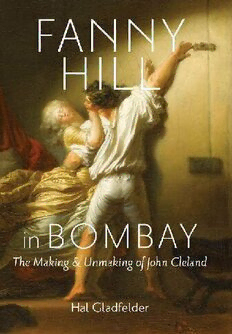

FANNY HILL in BOMBAY This page intentionally left blank FANNY HILL in BOMBAY The Making & Unmaking of John Cleland l Hal Gladfelder The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore © 2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2012 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gladfelder, Hal. Fanny Hill in Bombay : the making and unmaking of John Cleland / Hal Gladfelder. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978-1-4214-0490-5 (hdbk. : acid-free paper) isbn-10: 1-4214-0490-7 (hdbk. : acid-free paper) 1. Cleland, John, 1709–1789. I. Title. pr3348.c65z66 2012 828'.609—dc23 [B] 2011029770 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible. contents Acknowledgments vii John Cleland: A Chronology ix introduction “Old Cleland” 1 chapter 1 Fanny Hill in Bombay (1728–1740) 15 chapter 2 Down and Out in Lisbon and London (1741–1748) 37 chapter 3 Sodomites (1748–1749) 54 chapter 4 Three Memoirs (1748–1752) 85 chapter 5 The Hack (1749–1759) 139 chapter 6 The Man of Feeling (1752–1768) 177 chapter 7 A Briton (1757–1787) 213 epilogue Afterlife 238 Appendix. Cleland’s Mémoire to King João V of Portugal (1742) 245 Notes 249 Bibliography 289 Index 303 This page intentionally left blank acknowledgments For help in locating archival and rare published materials, I would like to thank the librarians, archivists, and readers’ assistants at the British Library (especially staff working with the India Office Collection in the Asian and African Studies reading room); the British National Archives, Kew; the Bodleian Library, Ox- ford; the Lambeth Palace Library, London; the John Rylands Library, Deansgate; and the John Rylands University Library at the University of Manchester. The staff and librarians at the Rush Rhees Library of the University of Rochester were also of great help in this project’s early days. Some of my preliminary re- search was carried out during a period of sabbatical leave from the University of Rochester, and the manuscript was drafted and largely completed during a yearlong research leave jointly supported by the University of Manchester and an Arts and Humanities Research Council fellowship. A portion of chapter 3 appeared in different form as “In Search of Lost Texts: Thomas Cannon’s Ancient and Modern Pederasty Investigated and Exemplify’d,” Eighteenth-Century Life 31:1 (2006): 22–43. I thank Duke University Press for permission to include a revised version here, and the journal’s editor, Cedric D. Reverand II, for his exacting and astute close reading. Other portions of chap- ters 3 and 4 appeared in different form under the title “Plague Spots” in Social Histories of Disability and Deformity, edited by David M. Turner and Kevin Stagg (New York: Routledge, 2006), 56–78. Still other portions of chapter 4 formed part of the introduction to my edition of Cleland’s Memoirs of a Coxcomb (Pe- terborough: Broadview, 2005); I thank Julia Gaunce, Barbara Conolly, Leonard Conolly, and Colleen Franklin for their help in bringing that project to comple- tion. Thanks also to Matthew McAdam, my acquiring editor at the Johns Hop- kins University Press, and to George Roupe for his meticulous copy editing. Peter Sabor and William H. Epstein were kind enough to read drafts of the first three chapters, and I am grateful both for their comments and for their viii Acknowledgments pioneering work on Cleland, which has inspired my own. Thomas Keymer read the entire manuscript and made invaluable suggestions for improving it; the faults that remain, of course, are my own. For giving me the opportunity to present this work to diverse audiences, I want to thank Monika Fludernik, Greta Olsen, and Jan Albers (University of Freiburg); Tim Hitchcock (Insti- tute for Historical Research, London); and Shohini Chaudhuri (University of Essex). For advice, solidarity, conversation, and other forms of moral or intel- lectual support, my thanks to Hans Turley (much missed), Lúcia Sá, George Haggerty, John Richetti, Noelle Gallagher, Brian Ward, Jill Campbell, Kathryn King, Bette London, Tom DiPiero, Ruth Mack, Rachel Ablow, Laura Rosenthal, Corrinne Harol, Morris and Georgia Eaves, Victoria Myers, Max Novak, and Ruth Yeazell. Although I can’t name them all here, colleagues at the University of Rochester and, now, the University of Manchester have provided warm and intellectually vibrant environments to work in. Through the whole writing process, Laura Doan, Marlene Mussell, and Ja- net Wolff cheered me on and celebrated every tiny milestone. Far away though they are, I want to send this out to my family: Anne Morgan; Glenn and Dale Gladfelder; and Kari and Tobbe Johansson. Closer to home, Oliver, Emilia, and Sophie played a vital creative (and sometimes destructive) part in the writing: ideal collaborators. The most vital part, though, was played by Jeff Geiger, writ- ing away in the next room while I wrote this, and who came with me to walk around Cleland’s old haunts. john cleland: a chronology 1710 Born, probably late summer, Kingston-upon-Thames, near London; first child of William Cleland, former army officer and civil servant, and Lucy DuPass Cleland; christened 24 September. 1721 Enrolls as student at Westminster School, January; withdraws, for reasons unknown, in 1723. 1728 Arrives in Bombay as a soldier in the service of the British East India Company and lives there until 1740, advancing to the position of junior merchant and becoming secretary to the governing Bombay Council. 1730 According to his own later statements, begins writing Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure in collaboration with Charles Carmichael (born ca. 1712). 1733 Death of Charles Carmichael, 24 July. 1734 Becomes embroiled in two legal cases: one initiated by William Boag, seaman, who charges JC with abducting Boag’s female servant, Mar- thalina (decided in favor of JC in September 1735); the second initi- ated by Henry Lowther and Robert Cowan, members of the Bombay Council, who lodge complaints against JC for injurious language (December 1734; case sent to the Company Directors in London for adjudication; decided in favor of JC, 1736). 1736 Arrival in Bombay of sister, Charlotte Lucy (or Louisa) Cleland, listed as a resident from 25 October. The following year, on 24 June, she marries George Sadleir, and on 3 October 1739 their son John is born; by 4 December 1739 he had died of “flux.” Charlotte would continue to live in Bombay until September 1740 and from October 1743 until her death (in Surat) in October 1747.