Experience of Nothingness PDF

Preview Experience of Nothingness

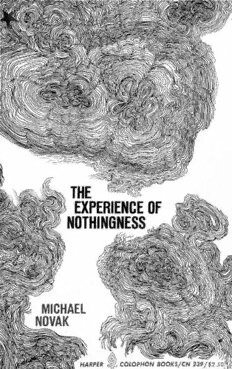

MICHAEL NOVAK The Experience of Nothingness MICHAEL NOVAK HARPER COLOPHON BOOKS Harper & Row, Publishers New York, Hagerstown, San Francisco, London For Karen, Richard, and Tanya — Experience o f Everything The Experience of Nothingness. Copyright ©1970 by Michael Novak. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 10 East 53rd Street, New York, N.Y. 10022. Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto. First harper colophon Edition published 1971 Standard Book Number: 06-090239-6 Contents I. The Experience of Nothingness 1. The Pursuit of Happiness? i 2. The Experience of America 4 3. In Europe: Nihilism 10 4. The Four Myths of the University 16 5. Story, Myth, and Horizon 23 II. The Source of The Experience 1. America’s Commitment to Objectivity 30 2. Three Doubts About Objectivity 36 3. The Drive to Raise Questions 44 4. Honesty and Freedom 51 5. Courage and Community 58 III. Inventing the Self 1. Action Is Dramatic 65 2. Decision Lies with Discernment 72 3. Three Myths of the Self 79 4. Truth Is Subjectivity 83 IV. Myths and Institutions 1. The Sense of Reality 89 2. The Tool 97 3. Politics and Consciousness 106 4. Nothingness and Reality 114 Acknowledgments The author is grateful to the following sources for the use of published materials: American Academy of Arts and Letters for Daedalus: Symbolism in Religion and Literature. The Estate of Henry James for the letter from William James. The Free Press for World Politics and Personal Insecurity by Harold Lasswell. Harvard University Press, The Loeb Classical Library, for Aristotle: The Nicomachean Ethics (H. Rackham, trans.). John Hopkins Press for Mind: An Essay on Human Feelings by Suzanne Langer. Little, Brown & Co. for The Thought and Character of William James by Ralph Barton Perry. McGraw-Hill Book Company for Soul on Ice by Eldridge Cleaver. David McKay Company, Inc. for The Varieties of Religious Experience by William James. Newman Press for The Ascent oj Mount Carmel by St. John of the Cross (E. A. Peers, trans.). W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. for Identity: Youth and Crisis and Insight and Responsibility by Erik Erikson. Pantheon Books, Inc. for The Politics of Experience by R. D. Laing and Madness and Civilization by Michel Foucault. Random House for The Stranger by Albert Camus; Culture Against Man by Jules Henry; The Will to Power by Friedrich Nietz sche (Walter Kaufmann, trans.). University of Illlinois Press for The Symbolic Uses of Politics by Murray Edelman. Preface to the Colophon Edition The response to the hardcover edition of this book taught me two things. First, older readers seem to have broken through the American “system of meaning” more thoroughly than younger readers. Many of the young still seem to be tempted by traditional American illusions—that the annunciation of moral goals is itself a moral act, that moral energy is the same as or better than political energy, that “progress” will come more or less automatically from good will (or other changes in consciousness), that morality consists in the individual’s “doing his thing” (hoary laissez faire), that there lurks up ahead somewhere, behind a hidden door, under a tree, within some hidden cave, a greening light of hope and prosperity and bliss: some magical dream drawing all Americans onward. Many Americans, old and young, have seen too much, and absorbed too much pain to go on believing in mirages. Life is much more terrifying than easy hope pretends. Ugly, boring, painful, vastly disillusioning experiences stalk our lives. There is much more solitude in life than anything in the ideology of our education teaches us. The gratifications and excitements of upward mobility sooner or later abandon us to the dizzying inner spaces of our rootlessness. To be sure, many Americans desire to cover over inner terror, to shrug it off as momentary weariness, to brighten and to ‘Smile and to look for something “constructive” to do. Many keep faith. But others grow. The generation that went to college in the fifties, my own genera tion, was preparing itself for the long haul. We were somewhat “silent.” But also serious. The young who followed us, in the sixties, burnt their candles at both ends, in spectacular light. Each genera tion has its own strength, and weakness. Ours knows well the experience of nothingness, the contours of compromise and illu sion, the masks of security. If we no longer seem to hope—do not believe it is from weakness; it is from strength. Facile and illusory American hope has no power over us. Our hope is an acceptance of despair. The second insight critical reaction brought to me is that many vii The Experience of Nothingness do not take seriously enough the nothingness of the experience of nothingness. Many who enter into the experience never emerge again. Insanity, pretense, mere conventionality, no-think, suicide, cynicism, egocentrism, a wild drug-taking race toward an early death, an intense desire to be consumed like flame—have we not seen in the last decade countless forms of self-destruction in the name of inner emptiness? It is not by chance that films like Bonnie and Clyde, Easy Rider, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and even Joe end in orgies of blood and death. It is not by chance that so many cultural heroes end up dead with needle-pointed arms in chill hotel rooms far from their homes. Listen to the wild beat of rock: hear the intensity of death. I am far from trying to show that our nothingness is unreal, further still from pulling a rabbit of hope out of a hat. Let those who wish to commit suicide commit suicide: I lay no imperative upon anyone. What has caught my eye in the history of nihilism is that Nietzsche, Sartre, and others wrote books: a most committed and disciplined use of time. The same drive that led them to the experience of noth ingness seemed to teach them other values as well—and without contradiction. Today, in any case, the experience of nothingness is simply a fact: many of us have it. What did we have to do to get it? It arises only under certain conditions. What are these conditions? The form of the question as it arises today is: Granted that I have the experience of nothingness, what shall I do with it? Perhaps nothing at all. Perhaps kill myself, go mad, look for a cause, turn on the radio, look for someone to hug, lie down and fall into an endless sleep, become a sleepwalker, drift, pretend . . . The possibilities are limitless. To my knowledge, no one who has reflected upon the experience of nothingness has called attention to the unique moral conditions under which it appears. These conditions do not disappear when the experience of nothingness seeps like fog into one’s consciousness. There is no obligation to notice what these conditions are. There is no obligation, once noticing them, to reinforce them and to build one’s life upon them. That is only one choice among many. That is merely something we can do, if we wish, without falsifying the experience of nothingness in the least. Preface This book, then, is at most an invitation. Notice, it says, every thing you can about what is happening to you. Do not avert your eyes from the commitments which are in fact, if you experience nothingness, already operating in you. You need not do either of these things. But you may. If you do, you “structure” the experience of nothingness—by calling operations within yourself into conscious ness, which you might otherwise not have noticed. So doing, you do not falsify the experience, do not cancel it, do not escape from it. It becomes a source of further actions, actions which are by so much without illusion. (“By so much.” Are men every wholly without illusion? No.) From year to year, the experience of nothingness grows deeper in one’s life, takes a more inclusive and profounder hold. By no means is this book intended to remove, cover over, or alleviate that experience. I want to unmask one piece of ideology only—that the experience of nothingness necessarily incapacitates one from further action. Every form placed upon the experience of nothingness is ideologi cal, including the form suggested here. The one advantage I claim for the course I have followed is that it keeps open the cellar doors; the cool draughts of the experience of nothingness remain one’s constant companion, one’s constant critic, one’s constant stimulus. If you desire to possess everything, desire to have nothing. Finally, the reflections on political action in Chapter IV are not meant to heap contempt on democratic forms of political life. They are intended to point out the void whence these forms spring, which they do not cover. Democracy is an illusory form of government. Although among illusions it is the least murderous, its hands too know blood, dry and caked, freshly red. We work as in a darkness- work, and yet do not wish to be deceived. If everything is meaning less, we come to such perception only through a most scrupulous fidelity, an honorable fraternity. If these too are meaningless, they remain one disposition open to us. They invite, they do not compel. Granted that we have the experience of nothingness, what shall we do with it? January, 1971 M ich ael N ovak ix « Note This brief philosophical essay was first prepared for delivery as the four Bross Lectures at Lake Forest College in January 1969. I am grateful to President William Graham Cole, Dean William Dunn, Professor Forest W. Hansen, and members of the community at Lake Forest for having invited me and for having responded to my work with generosity and warmth. To Dean Dunn, who arranged everything, I owe special thanks. Kathy Mulherin offered invaluable research assistance, household confusion, and entertainment to our children. Sharon Winklhofer and Terry Linnemeyer typed, and typed, and typed. Prologue This philosophical voyage may be construed as a meditation on following poem: On a dark night, Kindled in love with yearnings— oh, happy chance!— I went forth without being observed', My house being now at rest. In darkness and secure, By the secret ladder, disguised —oh, happy chance! In darkness and in concealment, My house being now at rest: In the happy night, In secret, w/re/i none saw me, Nor I beheld aught, Without light or guide, save that which burned in my heart. This light guided me More surely than the light of noonday, To the place where he (well I knew who!) was awaiting me— A place where none appeared. St. John of the Cross “Prologue,” Ascent of Mount Carmel