England’s Secret Weapon PDF

Preview England’s Secret Weapon

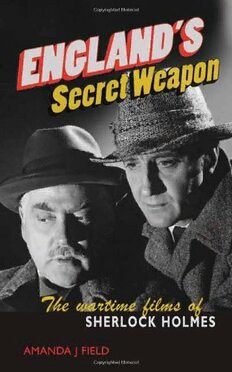

Contents Front Matter .....................................................3 Title Page .....................................................3 Publisher Information ...................................4 List of Illustrations ........................................5 Acknowledgements ........................................8 England’s Secret Weapon ...................................9 Introduction .................................................9 The Game’s Afoot ........................................32 ‘Watson - The Needle!’ .................................75 This Blessed Plot, This England ..................119 A Mythical Kingdom ................................161 Feline, Not Canine ...................................204 Conclusion ...............................................245 End Matter....................................................252 Bibliography Of Works Cited .....................252 Books ...................................................252 Periodicals ............................................261 Websites ...............................................265 Unpublished Sources .............................266 Filmography .............................................275 Also Available ...........................................289 ENGLAND’S SECRET WEAPON The Wartime Films of Sherlock Holmes Amanda J. Field Publisher Information First published in 2009 by Middlesex University Press Fenella Building The Burroughs Hendon London NW4 4BT www.mupress.co.uk Digital Edition converted and distributed in 2012 by Andrews UK Limited www.andrewsuk.com Copyright ©2009, 2012 Amanda J. Field All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic,mechanical,photocopying, recording or otherwise,without the prior written permission of the copyright holder for which application should be addressed in the first instance to the publishers.No liability shall be attached to the author, the copyright holder or the publishers for loss or damage of any nature suffered as a result of reliance on the reproduction of any of the contents of this publication or any errors or omissions in its contents. List of Illustrations Fig. 1: Frederic Dorr Steele illustration for Collier’s magazine (1903) Fig. 2: William Gillette as Holmes Fig. 3: Eille Norwood as Holmes (1920s) Fig. 4: Clive Brook as Holmes (1929) Fig. 5: Arthur Wontner as Holmes (1930s) Fig. 6: The Hound of the Baskervilles poster (1939) Fig. 7: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes poster (1939) Fig. 8: Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror poster (1942) Fig. 9: Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon poster (1942) Fig. 10: Sherlock Holmes in Washington poster (1943) Fig. 11: The Scarlet Claw poster (1944) Fig. 12: The House of Fear poster (1945) Fig. 13: Spider Woman poster (1944) Fig. 14: The Pearl of Death poster (1944) Fig. 15: The Woman in Green poster (1946) Fig. 16: Terror by Night poster (1946) Fig. 17: Dressed to Kill poster (1946) Fig. 18: A distinctive profile: Rathbone in The Hound of the Baskervilles Fig. 19: Graveyard in The Hound of the Baskervilles Fig. 20: Staircase to 221B Baker Street in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes Fig. 21: Filming The Hound of the Baskervilles on the cyclorama sound stage Fig. 22: Lamplighter in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes Fig. 23: Victorian city-wear in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes Fig. 24: Dr Mortimer meeting Sir Henry off the ship in The Hound of the Baskervilles Fig. 25: ‘Wasp waist’ costume in The Hound of the Baskervilles Fig. 26: Ann Brandon’s ‘arrow’ hat in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes Fig. 27: Mediaeval dress in The Hound of the Baskervilles Fig. 28: Needle cartoon from The Hound of the Baskervilles pressbook Fig. 29: Denis Conan Doyle letter from Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror pressbook Fig. 30: ‘East Wind’ setting in Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror Fig. 31: Newsreel-style opening to Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror Fig. 32: Swiss bierkeller in Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon Fig. 33: Interior of 221B Baker St in Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror Fig. 34: Typical modern art deco room of the 1940s Fig. 35: Men from the ministry in Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror Fig. 36: Soundwave monitor in Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror Fig. 37: Watson in hallway in Sherlock Holmes Faces Death Fig. 38: ‘VR’ bullet-holes in Sherlock Holmes Faces Death Fig. 39: ‘The Creeper’ in The Pearl of Death Fig. 40: Spanish lobby card for The House of Fear Fig. 41: Firelit café in The Scarlet Claw Fig. 42: Inside the church, from The Scarlet Claw Fig. 43: Shipboard scene in The Pearl of Death Fig. 44: Nightclub in The Woman in Green Fig. 45: Sari costume in Spider Woman Fig. 46: Clawlike dress in Spider Woman Fig. 47: Phallic hat in Spider Woman Fig. 48: Interior of Adrea Spedding’s apartment in Spider Woman Fig. 49: Actress Evelyn Ankers in pressbook for The Pearl of Death Fig. 50: Vivian Vedder in Terror by Night Fig. 51: Booth’s Gin advertisement with Basil Rathbone Illustration sources and copyright acknowledgements The Arthur Conan Doyle Collection, Richard Lancelyn Green Bequest, generously made the following photographs from their collection available: Figs 1-2, 5-13, 15, 21, 23, 25, 27-28, 35-36, 46-47 and 50. A number of illustrations are screenshots (Figs 18-20, 22, 24, 26, 30-33, 37-39 and 41-43) taken by the author; all others not listed above are from the author’s own collection. All images from The Hound of the Baskervilles and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes are the copyright of Twentieth Century-Fox. All images from the other 12 films in the Holmes series are the copyright of Universal. The art deco room (Fig 34) is the copyright of the Geffrye Museum and the Booth’s Gin advertisement (Fig. 51) is the copyright of Booth’s Gin. Cover image: publicity photo of Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce as Sherlock Holmes and DrWatson in the 1942–1946 series of films from Universal. British Film Institute: Stills, Posters and Designs. Acknowledgements I am grateful to Portsmouth City Museum for the opportunity to work on the Arthur Conan Doyle Collection, Richard Lancelyn Green Bequest, from the initial receipt of the boxes through to final cataloguing, enabling me to have early access to many documents; and in particular to Sarah Speller for permission to use some of the stills in the Collection. Also to Ned Comstock at the University of Southern California for making the Universal production files for the films available; Lauren Buisson at UCLA for access to the Twentieth Century-Fox legal files; the Margaret Herrick Library for Production Code Administration files; the British Film Institute library for access to trade and consumer magazines; and Catherine Cooke at Westminster Libraries for access to books in the Sherlock Holmes Collection. Lastly, without the encouragement and enthusiasm of Dr Michael Williams of the University of Southampton, and the willingness of my husband John Bull to watch the Holmes series with me over and over again, this book would certainly not have come to fruition. Introduction ‘Though the world explode, these two survive And it is always eighteen ninety five’ Vincent Starrett1 It is midnight. Clouds scud across the face of the Houses of Parliament as Big Ben begins its familiar chime. The chime continues while the scene fades out to reveal a Baker Street road-sign lit by a gas flare: as the camera pans along a brick wall, the flare makes dimly visible ‘221B’ elegantly sign-written on the entrance door below. The scene cuts to a close-up of an article in The Times, about the arrival from Canada of Sir Henry Baskerville, heir to the Baskerville estate. In a midshot, we see Dr Watson seated comfortably at a library-table, scissors in hand, preparing to clip the item out of the paper. He complains to a pacing, dressing-gowned Holmes that he can’t understand why Holmes wants all the clippings about ‘this Baskerville fellow’. ‘My conjecture’, replies Holmes, as the camera cuts to his face in profile, ‘is that he’ll be murdered’. ‘Murdered?’ echoes a baffled Watson. ‘It will be very interesting to see if my deductions are accurate’, replies Holmes, sucking contemplatively on his calabash pipe. After some showy deductions about a walking stick, left behind earlier that evening (Watson confidently getting it all wrong, and Holmes affectionately putting him right), the door opens and Mrs Hudson ushers in the stick’s owner, Dr Mortimer. ‘Mr Holmes’, the man says in an urgent tone, ‘you’re the one man in all England who can help me’. This scene, from The Hound of the Baskervilles, a Twentieth Century-Fox film released in 1939, contains the first glimpse of Basil Rathbone as Holmes and Nigel Bruce as Watson in what would become a long-running series spanning the years of war in Europe. It introduced viewers to a new interpretation of Sherlock Holmes, a character with whom they probably already had considerable [1] Starrett (1942) unpaginated. familiarity gained through the Doyle stories, previous film and stage ‘incarnations’, radio series, comic strips, parodies, or a combination of all these. Holmes had been a transmedia figure for more than 40 years when this film was released: in terms of cinema alone, this was his 100th appearance and Basil Rathbone was the 23rd actor to play the character. This meant that audiences would have certain preconceptions of how Holmes should look and behave, and would judge this new interpretation as to whether it represented the ‘real’ Holmes. Which particular point of origin they would use as a yardstick is, however, debatable: Christopher Frayling has pointed out just how far from the literary ‘original’ these perceived constructs can stray: Frankenstein has become confused with his own creation....Dracula has become an attractive lounge lizard in evening dress; Mr Hyde has become a simian creature who haunts the rookeries of Whitechapel in East London; and Sherlock Holmes, dressed in his obligatory deerstalker and smoking a meerschaum pipe, says ‘elementary my dear Watson’ whenever he exercises his powers of deduction. Not one of these re-creations came directly from the original stories on which they were based: successive publics have re-written them - filling in the gaps, re-directing their purposes, making them easier to remember and more obviously dramatic - to ‘fit’ the modern experience.2 Although Frayling’s comments were written from the perspective of the 1990s, they are equally applicable to the representation of these characters in 1939. Holmes’ evolution had been gradual, involving layers of accretions that had built onto the original Doyle creation, such as the deerstalker hat, drawn on the character by Sidney Paget in his illustration of ‘The Boscombe Valley Mystery’ for The Strand [2] Frayling (1996) p.13. Thomas Leitch makes similar observations about the accrual of characteristics (Leitch 2007:209).