Ecology of a Changed World PDF

Preview Ecology of a Changed World

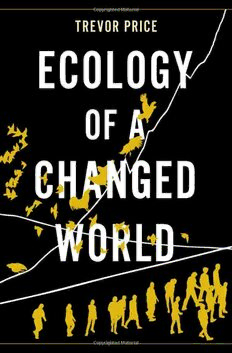

Ecology of a Changed World Front cover: Between 1970 and 2021, the number of people in the world doubled to nearly 8 billion and the number of chickens increased fivefold to 26 billion. The number of wild birds in North America declined by 30% (the illustration runs to 2017, when bird abundances were estimated). There may now be fewer birds in North America than people in the world. See Figures 11.2, 12.3, and 24.5. Illustration by Allison Johnson. Ecology of a Changed World TREVOR PRICE University of Chicago, Chicago Illustrated by AVA RAINE 1 3 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America. © Oxford University Press 2022 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging-i n- Publication Data Names: Price, Trevor, 1953– author. Title: Ecology of a changed world / Trevor Price ; illustrated by Ava Raine. Description: New York : Oxford University Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2021029388 (print) | LCCN 2021029389 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197564172 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197564196 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: Ecology. | Global environmental change. | Biodiversity—Environmental aspects. Classification: LCC QH541. P735 2021 (print) | LCC QH541 (ebook) | DDC 577—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021029388 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021029389 DOI: 10.1093/o so/ 9780197564172.001.0001 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America Royalties for this book will be donated to savingnature.org Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments ix About the Companion Website xi 1. The Changed World 1 PART 1. THE RISE AND FALL OF POPULATIONS 2. Population Growth 9 3. Population Regulation 21 4. Interactions between Species: Mutualisms and Competition 31 5. Predation and Food Webs 43 6. Parasites and Pathogens 52 7. Evolution and Disease 64 8. The Human Food Supply: Competition, Predation, and Parasitism 75 9. Food Security 83 PART 2. THE THREATS TO BIODIVERSITY 10. Prediction 97 11. Human Population Growth 110 12. Growth of Wealth and Urbanization 121 13. Habitat Conversion 132 14. Economics of Habitat Conversion 143 15. Climate Crisis: History 155 16. Predictions of Future Climate and its Effects 166 17. Pollution 176 18. Invasive Species 184 vi Contents 19. Introduced Disease 194 20. Harvesting on Land 205 21. Harvesting in the Ocean 215 22. Harvesting: Prospects 226 PART 3. AVERTING EXTINCTIONS 23. Species 239 24. Population Declines 248 25. Extinction 261 26. Species across Space 273 27. Island Biogeography and Reserve Design 283 28. The Value of Species 294 Notes and References 303 Subject Index 331 Species Index 337 Preface This book has been updated over 15 years in order to keep up with the rapid changes of the twenty-fi rst century, and it will continue to be updated through an associated website, which also contains appendices to chapters, and worked examples. The coronavirus pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement, excep- tional fires and heatwaves exmplify the changes and the challenges of our times. A book on the science behind the biodiversity crisis has much to say about the pandemic and climate change. The SARS CoV- 2 virus crossed into humans most likely from the hunting of bats for food. So, we might ask, what would happen if there were no bats in the world? The science is clear. Every time a species is lost, others become more common, making new disease transmission and virulence even more likely. We can see this in the rapid spread of coronavirus through the dense human population. We can also observe more directly effects of bat loss in North America, where white nose disease inadvertently introduced from Europe in 2006 has killed millions of bats, which in turn has been linked to increased insecticide use by farmers attempting to combat the insect pests the bats would otherwise have eaten. This book moves beyond specific examples and beyond disease. We want to quantify biodiversity loss and the consequences for human well- being as we go forward. What about Black Lives Matter? As sports writer Barney Ronay put it: “so much unhappiness is created, so much talent is lost, so many people who should be doing things and have opportunities to do those things, don’t receive those opportunities.” (Complete citations are in the references section at the end of the book.) What can we say about connections between these injustices and con- servation? Asymmetries and inequalities lie beyond race. They include gender, sexual orientation, disability, caste, religion, nationality, and wealth. Such inequalities are not only morally indefensible, but contribute to the crisis of na- ture. As a middle-c lass white male, my concern with the natural world comes from privilege and past experience. Others have not had this same fortune, and one feels that nothing but good could come out of more such opportunity. In this book I focus on one important inequality: that of wealth. Aside from the other benefits of having money, many are not able to buy enough food, de- spite there being more than enough food now produced to feed everyone. Like other forms of inequality, poverty is not something I have personally had to deal with, but it is something I have witnessed firsthand, working in India. Wealth disparities impact conservation greatly, from the direct effects of being poor viii Preface (e.g., it leads people to hunt bats) to the more general lack of opportunity that is associated with all types of discrimination. Within countries, wealth inequality continues to increase, but the economic growth of Asian and South American countries has meant that across the world inequality has been decreasing, at least until the recent economic downturn. On average, people have been becoming richer and healthier, and we hope this trend will pick up again soon. Such wel- come changes have huge implications for the conservation of biodiversity. These changes are covered in the book, and many of the consequences surely apply more generally to the mitigation of all social injustices. Acknowledgments Chris Andrews, Bettina Harr, Julia Weiss, and several anonymous reviewers read the whole book. Various pieces have been read by Erin Adams, Sarah Cobey, Ben Freeman, Peter Grant, Sean Gross (who made the compelling suggestion to delete a chapter), Rebia Khan, Kevin Lafferty, Karen Marchetti, Robert Martin, Natalia Piland, Yuvraj Pathak, Uma Ramakrishnan, Mark Ravinet, Matthew Schumm, David Wheatcroft, and anonymous reviewers. Many people have responded to requests for information, including David Archer, Sherri Dressel, Clinton Jenkins, David Gaveau, Kyle Hebert, David McGee, Loren McClenachan, Nate Mueller, Natalia Ocampo- Peñuela and Stuart Sandin. The copy editor, Betty Pesagno, made an excellent and thorough review. Kaustuv Roy has always been supportive and a great friend. I appreciated the R programming environment (citations are in the Notes and References section at the end of the book). I par- ticularly wish to thank Angela Marroquin and Bettina Harr for much help with the figures and Ava Raine for her outstanding drawings. The book is dedicated to local activists, who are at the frontline of conserving the planet’s biodiversity, sometimes at considerable risk to themselves. They in- clude Homero Gómez González and Raúl Hernández Romero, who were mur- dered in 2020, apparently by illegal loggers. Their work involved conserving the winter habitat of the emblematic monarch butterfly which migrates from the eastern United States to a few mountain tops in central Mexico. Not so long ago the monarch population numbered in the many hundreds of millions, but in the last 10 years, never more than 100 million (Chapter 24).