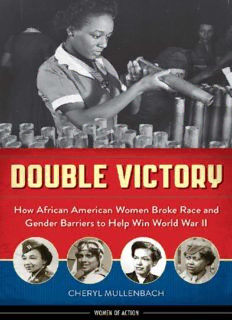

Double Victory: How African American Women Broke Race and Gender Barriers to Help Win World War II PDF

Preview Double Victory: How African American Women Broke Race and Gender Barriers to Help Win World War II

Copyright © 2013 by Cheryl Mullenbach All rights reserved First edition Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-56976-808-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mullenbach, Cheryl. Double victory : how African American women broke race and gender barriers to help win World War II / Cheryl Mullenbach. — 1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-56976-808-2 (hardcover) 1. World War, 1939-1945—African Americans. 2. World War, 1939-1945— Women—United States. 3. African American women--History—20th century. 4. African American women—Employment—History—20th century. 5. United States—Race relations--History--20th century. 6. African American women—Civil rights—History—20th century. 7. African Americans— Employment. 8. African Americans—Civil rights. I. Title. D810.N4M85 2012 940.53082’0973—dc23 2012021343 Interior design: Sarah Olson Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Zola (Emerson) Mullenbach—One of the greatest of the “greatest generation” Richard L. Wohlgamuth Jake, Bailey, Zack, Brooklyn, Ty, Sophia, and Emerson In memory of Ralph Mullenbach CONTENTS Introduction 1 WAR WORKERS “Negroes Cannot Be Accepted” 2 POLITICAL ACTIVISTS “I Am Not a Party Girl, I Want to Build a Movement” 3 IN THE MILITARY “Will All the Colored Girls Move Over on This Side” 4 VOLUNTEERS “Back the Attack” 5 ENTERTAINERS “We Don’t Take Your Kind” Epilogue Notes Bibliography Index INTRODUCTION In 2002, Thomasina Walker Johnson Norford died quietly in her sleep at the age of 94. The New York Amsterdam News described her as “the epitome of elegant refinement, culture, and determination.” Her parents, who were long dead, would have been pleased and proud to know that their daughter had retained her elegance and refinement in her old age. But they most likely would have been surprised, considering the direction their daughter’s career had taken. When Thomasina was growing up, her parents had tried to convince her that “nice little girls are not interested in politics and labor unions, they teach.” Thomasina tried to obey her parents—she became a teacher. But when she ran into problems because she was black, she left the teaching profession. Thomasina turned to politics and labor unions—becoming an influential lobbyist in Washington, DC, where a woman in the halls of Congress was an unusual sight and where a black woman in a prominent professional position was almost unheard of in the 1940s. Professional opportunities for women of Thomasina’s generation were limited. But for women who were not white, the options were more restrictive. Yet Thomasina managed to overcome the double barriers of gender discrimination and race discrimination. She was one of a generation of women who did so. Thomasina was a young adult in the early 1940s, a time that was a turning point in American history. The world was at war—America entered World War II in 1941. As more and more men were needed to fight at the fronts, women were reluctantly accepted in now-vacant positions that had been previously closed to them. They entered the workforce in unprecedented numbers and became official members of the military for the first time in history. Female news reporters followed stories to the battlefields across war-torn lands. Female entertainers sang and danced across continents, performing for the fighting armies in Europe, Asia, and Africa. Women served in hospitals around the world, caring for the wounded and comforting dying soldiers. Although it was expected that, after the war, women would return to the lives they had led previously, there was no turning back for many—especially for black women. These women were part of what became known as “the greatest generation.” Thomasina was born in 1908—when the first Ford automobiles were selling for about $800. But in 1908 it was illegal for women to drive cars in some cities. It was the year before the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was formed. Eighty-nine black citizens were lynched in the United States that year. The women of the greatest generation were teenagers in the 1920s and ’30s. In 1920 the 19th Amendment was passed, allowing women to vote for the first time; however, black men and women were kept from voting through intimidation in most southern states. In 1925 the state of Georgia introduced a bill that made it illegal for a black person to marry a white person. In 1935 the NAACP petitioned the University of Maryland to explain its policy of admitting only whites to the university. In 1939 famed singer Marian Anderson was denied permission by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) to sing at their hall—Constitution Hall—in Washington, DC, because she was black. When America entered the war in 1941 no one could have anticipated the changes that would shape the future for women. But postwar America held hope for many black women. The opportunities that they took advantage of during the war years in the 1940s set the stage for the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s—decades that saw the emergence of the civil rights movement and the women’s movement. In the 1950s the women of Thomasina Walker Johnson Norford’s generation wondered what it would mean for their children when the US Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. They heard about a black woman named Rosa Parks who challenged life as it was in the South by refusing to give up her seat on a city bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Many Americans participated in marches that resulted in equal rights for women and minorities in the 1960s. In 1963 a man named Martin Luther King Jr. spoke about having a dream for future generations. The Civil Rights Act of 1964—outlawing discrimination in the workplace on the basis of sex or race— was passed by Congress. As the 1970s and ’80s dawned, Thomasina and the women of her generation began to enter their elder years. The US Supreme Court again took actions that were intended to bring equality to the nation’s education system when it ruled that busing of students could be used as a tool to force integration of public schools in America. Black and white women entered political life as never before. Many were encouraged when Sandra Day O’Connor became the first woman to serve on the US Supreme Court. And some wondered if victory over racism had really been achieved when race riots broke out in Los Angeles after a jury acquitted four white police officers of beating a black man. By the end of the 20th century, fewer and fewer women of Thomasina Walker Johnson Norford’s generation remained. Throughout their lives, many of their stories of triumph over the challenges they faced as women were overlooked. Many of their accounts of victory over racism were ignored. It’s up to the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren to recover the stories of the women who have gone—and to pay attention to the stories of the women who survive. It is their responsibility to ensure these victorious women are not forgotten. It will be a double victory. 1 WAR WORKERS “Negroes Cannot Be Accepted” I stood in line with the others, but a guard came up and said it was no need to wait; that there was no hiring of colored women. —Miss Ethel Bell In August 1944, factories across the country were in dire need of workers to build guns, bombs, planes, and ships for the US military. The country had been at war for almost three years. The government contracted with factory owners to provide the military with critical supplies, but thousands of men had left their factory jobs to join the fighting overseas. With the urgent need for skilled workers, defense plants looked first to unmarried white women to fill the positions. As the war effort mounted and the need for defense workers increased, the plants began to recruit and hire married white women. Some plants hired black men. Last to be considered for employment were black women. But in some plants the hiring of “colored” women was never a consideration because racial discrimination was an accepted practice in the America of the 1940s. When Ethel Bell responded to a newspaper advertisement seeking workers for jobs at a plant in St. Louis, Missouri, a guard made it clear to her that she wouldn’t be considered for employment because she was black. In 1944 it wasn’t against the law for a factory to refuse to hire someone because of race or gender. There was nothing Ethel could do to force the factory owner to look beyond the color of her skin and consider her skills and qualifications. Ethel went home without a job, and the factory owner continued with the profitable government contract. The Negro Problem Ethel was one of the many women who were eager to get jobs in the defense plants in the war years. The jobs paid well. Some of the jobs required special expertise and the workers were given opportunities to learn new skills. In addition, the women felt they were doing something to support the war effort at home while other family members were fighting the enemy overseas. The idea of women of any color working in factories was new to Americans in the 1940s. It was a time when most married women stayed home and worked as housewives while their husbands went to work outside the home. Some women worked in professional positions—as doctors, lawyers, teachers, and writers, for example—but those professions were dominated by men. Women with high school educations or less who worked outside the home often worked in service jobs as store clerks, waitresses, or house cleaners. Many black women worked as maids or “domestics” for white families. Life as a domestic included long hours and little pay. A typical workday was 12 hours, and most employers expected their domestics to be “on call” six days a week. The job duties included cooking, washing, ironing, cleaning, and serving meals. Sometimes domestics cared for the white families’ young children, too. The typical wage for a domestic worker was $7 a week. Domestic workers in southern states made as little as $3 to $4 a week. So when black women who worked as domestics heard about war jobs in defense plants that paid as much as $35 per week, they were interested in applying for those positions. The federal government created agencies to deal with issues related to war work. The War Manpower Commission was formed to deal with the labor shortage caused by the large number of men entering military service. The Office of War Information relayed news and information about the war to the public. The two agencies worked together to recruit women for the war industries. A government official from the War Manpower Commission said in an interview with Time magazine that as the nation geared up for war it would need to look for workers in untapped sources. He predicted that over 7 million people outside the paid workforce in the United States—92 percent of whom were women—could be convinced to “forsake kitchen or lounge for office and factory.” He warned that such a move would “shake U.S. living habits.” He explained, “More women in the war effort means fewer women in the home—as wives, daughters, or servants; it means eating more meals out, fewer socks darned, fewer guests entertained at home, and many another change in the

Description: