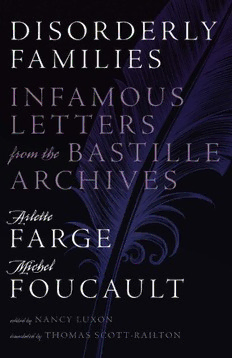

Disorderly Families: Infamous Letters from the Bastille Archives PDF

Preview Disorderly Families: Infamous Letters from the Bastille Archives

DISORDERLY FAMILIES This page intentionally left blank DI S O RD E RLY FA M I L I E S % Infamous Letters from the Bastille Archives ARLETTE FARGE and MICHEL FOUCAULT Edited by Nancy Luxon Translated by Thomas Scott- Railton Afterword to the English Edition by Arlette Farge University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis London Originally published in French as Le Désordre des familles: Lettres de cachet des Archives de la Bastille au XVIIIe siècle, by Arlette Farge and Michel Foucault. Copyright Gallimard/Julliard, 1982 and 2014. Cet ouvrage a bénéficié du soutien des Programmes d’aide à la publication de l’Institut Français. This work received support from the Institut Français through its publication program. Copyright 2016 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401- 2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu A Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN: 978-0-8166-9534-8 (hc) Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper The University of Minnesota is an equal- opportunity educator and employer. 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book was prepared in collaboration with Christiane Martin, who devoted herself to it until the end of her life. This task was completed by Éliane Allo, assistant at Collège de France. We thank her for her help and her important contribution to this project. ARLETTE FARGE and MICHEL FOUCAULT This page intentionally left blank % Contents Translator’s Preface · ix Editor’s Introduction · 1 Disorderly Families Introduction · 19 1. Marital Discord · 29 LETTERS Households in Ruin · 51 The Imprisonment of Wives · 65 The Debauchery of Husbands · 80 The Tale of a Request · 100 2. Parents and Children · 123 LETTERS The Disruption of Affairs · 139 Shameful Concubinage · 158 The Dishonor of Waywardness · 170 Domestic Violence · 192 Bad Apprentices · 208 Exiles · 216 Family Honor · 224 Parental Ethos, 1728: The Rationale for Sentiment · 231 Parental Ethos, 1758: The Duty to Educate · 242 3. When Addressing the King · 251 Afterword to the English Edition · 267 Arlette Farge Notes · 275 Glossary of Places · 315 Name Index · 319 This page intentionally left blank % Translator’s Preface Translating these requests for lettres de cachet presented several challenges— or at the very least decisions. To translate them from French into English I first had to address the question of which English. After some consideration, the three main options seemed to be (1) to translate them literally, directly, preserving the archaic French syntax and language; (2) to render them in an equivalent eighteenth- century English; and (3) to bring them into modern English, my native language. Each of these choices had something to recom- mend it. The first would leave the lightest footprint and result in the most “authentic,” albeit somewhat cumbersome, translations. Taking the second approach would offer the modern English reader the closest approximation of what French readers experienced when Le Désordre des familles was origi- nally published in 1982— texts that were written in an outdated but not unfamiliar style, one that would correspond the closest to the era that had shaped both these letters and their authors. If the first course could perhaps be said to be most authentic to the texts, adopting the third method would be the most authentic with regard to my- self. I was not raised in a culture that spoke eighteenth- century English, and therefore I could only craft a likeness, at worst a simulacrum, of it— like an actor whose Scottish accent bears no relation to how people actually talk in Aberdeen, but rather reflects a Hollywood idea of how a Scotsman should sound. And so I should translate these requests into the language in which I speak and write. After all, when they were written, were not these appeals composed in the vernacular of the time? But the incompatibility of these three paths, which appeared so stark when viewed at the level of abstraction, softened upon contact with the documents themselves. These elements were not mutually exclusive so much as in ten- sion, or various considerations to navigate by, to keep in mind, while being guided by the same central concern that had motivated the people who had written— or dictated to a public scribe— these requests: making them heard. Not just in their written pleas, but in all that these pleas revealed about them lies a concern that is not merely linguistic but is also individual. If all the requests were literally translated into the same clumsy English, or liter- arily rendered into smooth English (be it eighteenth or twenty- first century), the difference between a letter written by an educated government clerk and